The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb

A Glow Beneath the Earth

It was 1938, the world was at war, yet deep in the heart of Africa, a secret was waiting to be uncovered. In the Belgian Congo, amid thick forests and copper-rich hills, there was a mine few had heard of — Shinkolobwe.

The land was controlled by Union Minière, a Belgian mining company with deep colonial ties. In nearby villages, people spoke of strange rocks that glowed softly in the dark. European businessmen arrived quietly, chasing whispers of rocks said to be worth a fortune.

Beneath their feet lay something powerful — a hidden force that would one day cross oceans and help unleash the world’s first atomic bomb.

New Discoveries, New Tools of Violence

In 1938, scientists in Germany split the atom for the first time — and in that moment, the world changed. The discovery of nuclear fission unlocked the terrifying possibility of a weapon unlike anything before. Almost overnight, uranium went from a scientific curiosity to the most coveted substance on Earth. In secret labs and government offices, the United States and Britain launched a desperate search to find enough of it before their enemies did.

Germany and Japan were both in the race to build an atomic bomb, but they lacked one crucial ingredient: high-grade uranium. Most of the world’s deposits were low quality, containing only trace amounts. North American sources, for example, held less than 0.03 percent uranium. In contrast, buried deep in the Congo was Shinkolobwe — a remote, almost mythical mine with ore so rich it defied belief. Some samples contained as much as 65 to 75 percent uranium, making it the most potent natural source ever discovered.

Far from Africa, officials planned how to secure this precious mineral. Belgium was under Nazi German occupation, raising questions about who controlled the mine.

Edgar Sengier, director of the mining company, acted quietly. He arranged for 1,200 tons of uranium ore to be shipped to a warehouse in Staten Island, New York, weeks before the United States even asked for it. That ore would become critical for the Manhattan Project.

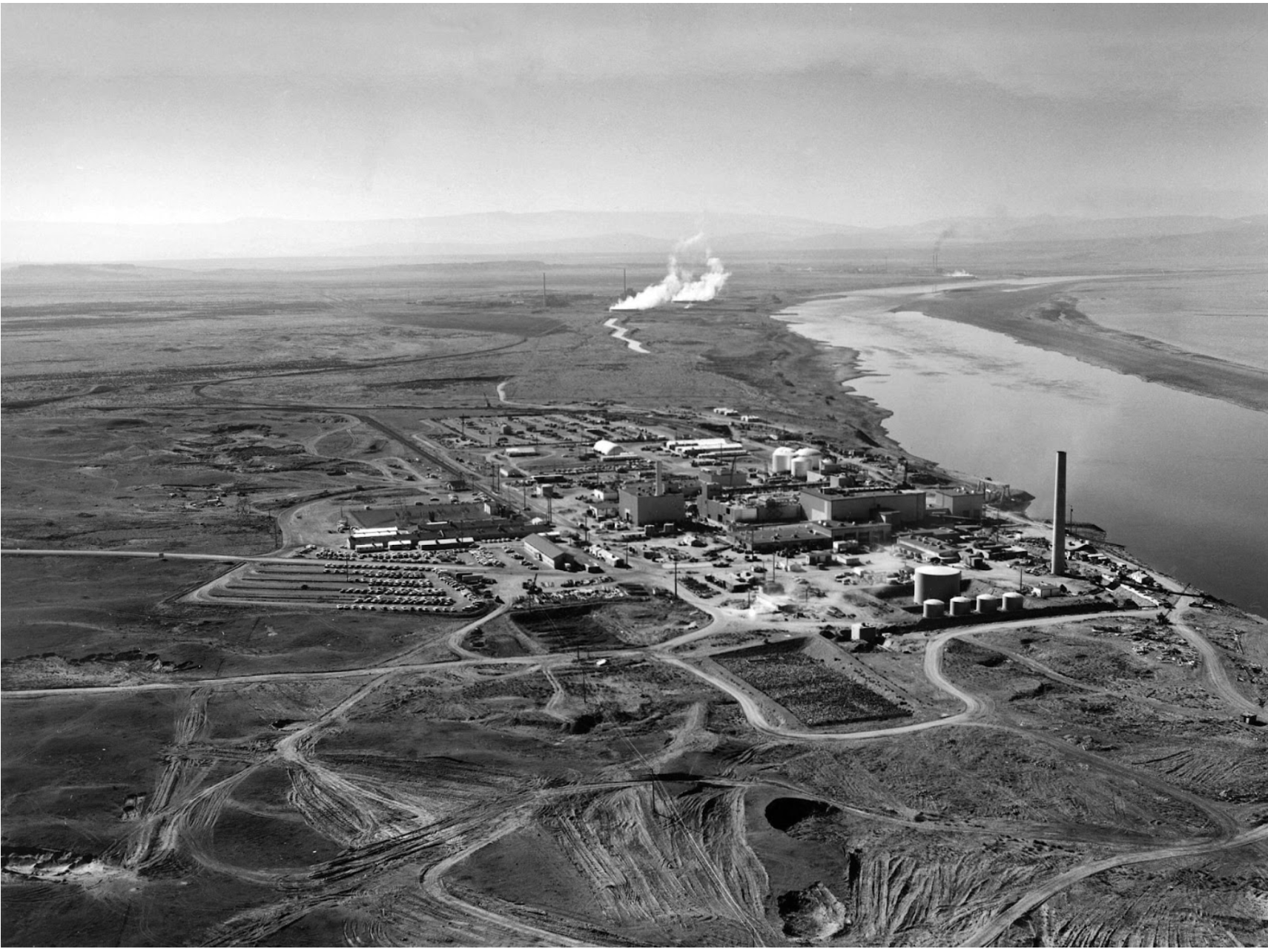

Iron Teeth and Hidden Cargo

Image Credit: Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility

In 1944, shipments of pitchblende — the radioactive rock containing uranium — were loaded into wooden wagons and burlap sacks. Each shipment was heavily guarded. Soldiers and spies made sure the ore did not fall into enemy hands. There were fears the Germans might try to steal it or that the Soviets could take it during the Cold War.

By the end of the war, over 8,000 tons of uranium oxide from the Congo had been delivered to the United States. Canadian mines supplied some uranium, but more than 70 percent came from Shinkolobwe.

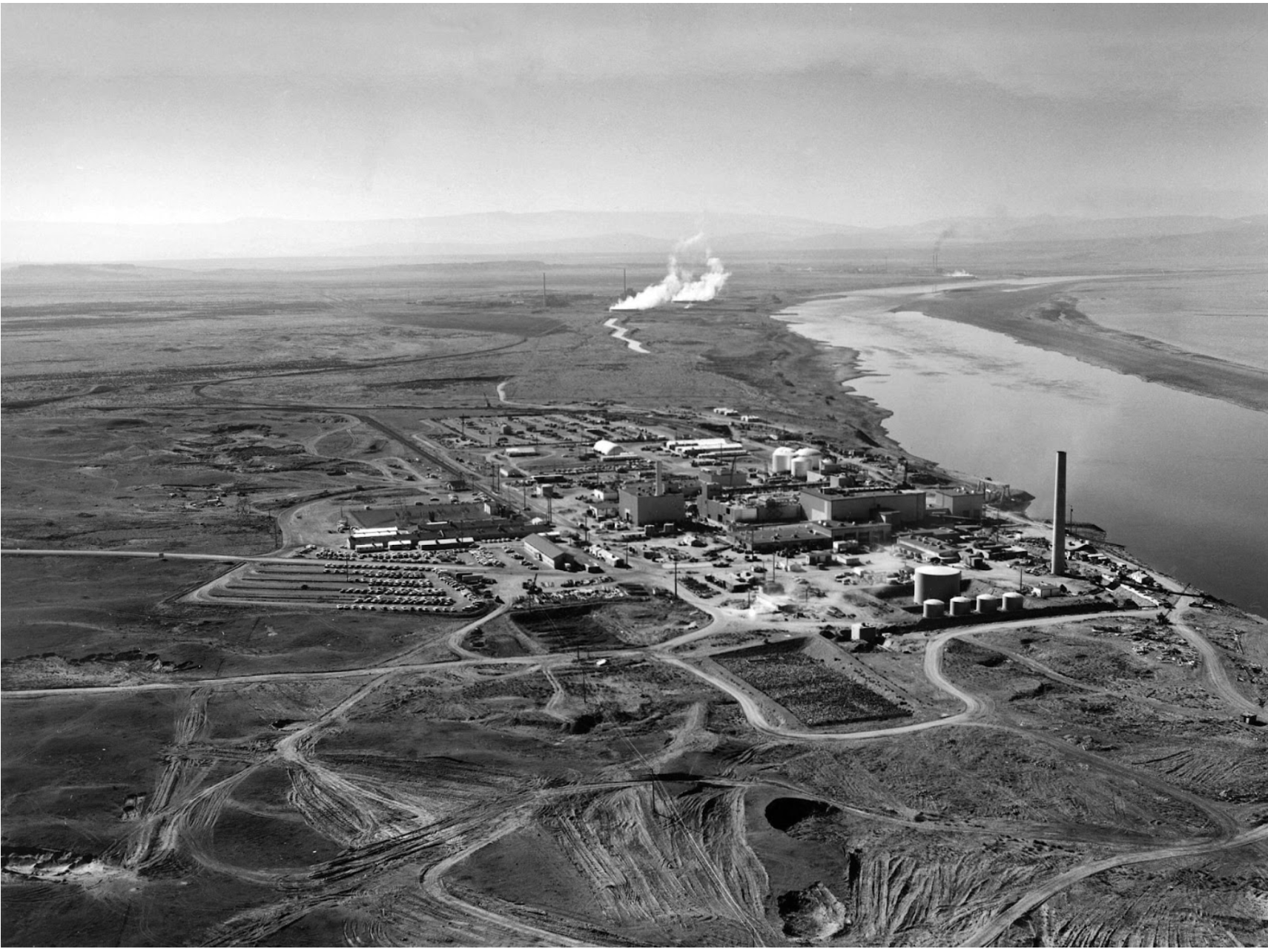

In July 1945, deep in the New Mexico desert, scientists at Los Alamos, such as those depicted in Oppenheimer, examined the uranium that had arrived months earlier. They understood exactly what it could do, and within weeks, their theories would turn into fire.

On August 6, 1945, a bomb called Little Boy fell on Hiroshima. Three days later, Fat Man devastated Nagasaki. The core ingredients for those bombs — uranium and plutonium — included highly concentrated uranium ore mined from the hills of Shinkolobwe in the Congo. It had traveled across oceans under armed guard, its origins buried in silence.

Today, this remains one of World War II’s most overlooked truths. While the world remembers the science and the scientists, few remember the African mine that powered it. A remote, forgotten corner of Congo provided the fuel for the most destructive weapons ever used.

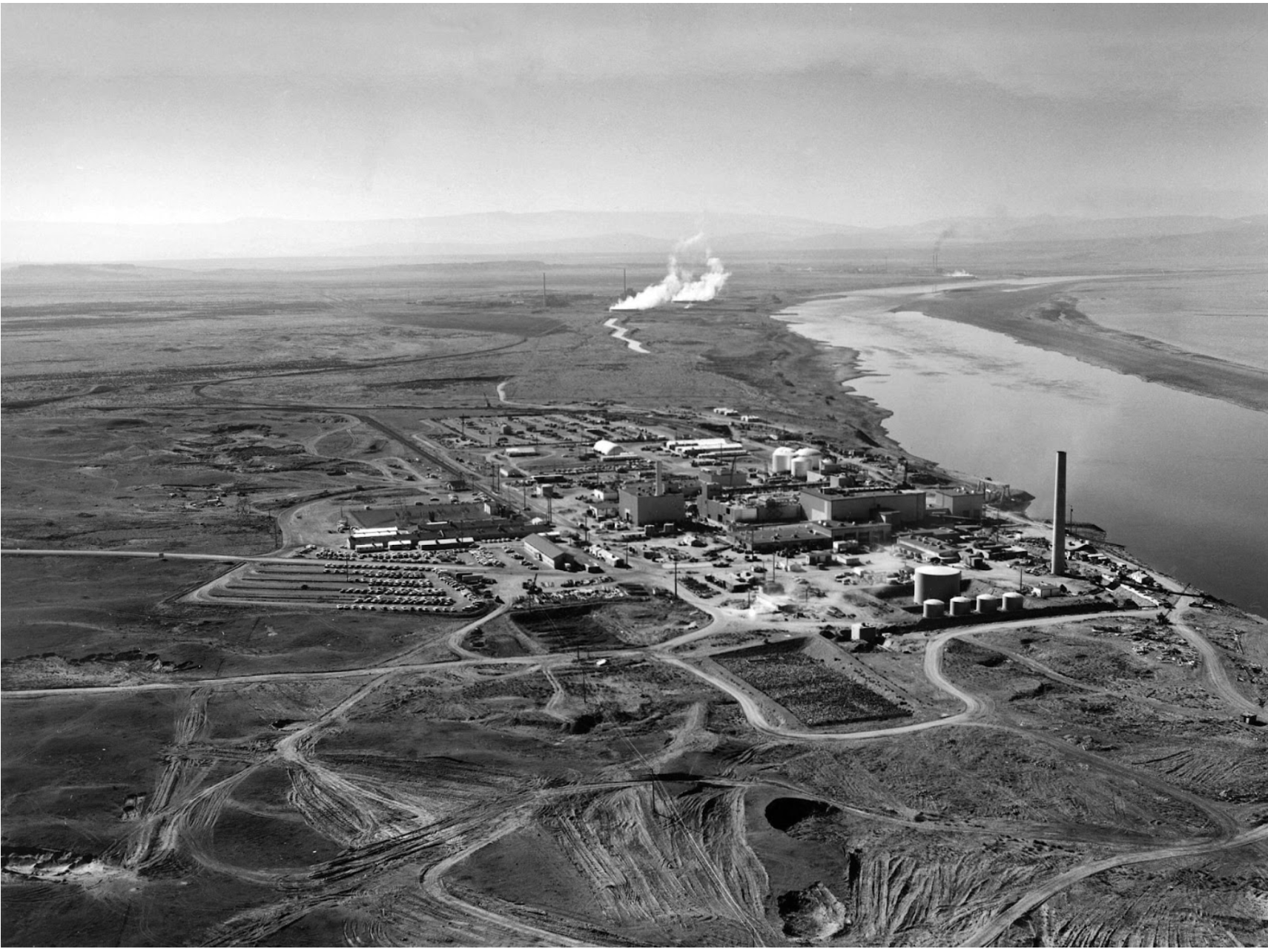

The Flesh Suffers

Image Credit: The Wired.

The human cost remained hidden behind layers of secrecy and silence. Congolese miners, often exploited and poorly paid, were sent deep into the earth with little more than cloth wraps and bare hands. They handled radioactive ore with no protective gear, no warnings, and no understanding of what it was doing to their bodies.

Many began to fall ill. Skin lesions. Chronic fatigue. Breathing problems. In some cases, cancers that appeared far too early. There were no health studies, no medical support, and no official recognition. What they had been mining was uranium — and prolonged exposure to its radioactive particles is known to damage organs, weaken immune systems, and cause genetic mutations.

These workers were not protected, and many were not even willing. Some were forced into labor under harsh colonial rule. They worked long hours under threat of violence. Historians would describe the operation as near-enslavement.

This Was Not Congo’s Last Decimation

The story did not end in 1945. During the Cold War, Shinkolobwe stayed a prize in global politics. Western powers guarded access carefully, fearing Soviet influence. The U.S. government negotiated to reopen the mine. Engineers drained shafts and improved infrastructure, all under strict secrecy. The mine’s location vanished from maps and few journalists were allowed inside.

Thankfully, In 1960, as Congo moved toward independence, the mine was officially closed, and the shafts were sealed with concrete. On paper, the danger was buried. In reality, it was only hidden.

Over time, informal miners began returning to the site. Most were searching for cobalt, a metal used in modern batteries and electronics. Without knowing it, they often disturbed uranium-rich rocks still buried underground.

Clouds of dust carried radioactive particles into their lungs. Water sources near the mine became tainted. Locals cooked, bathed, and drank from rivers that flowed through contaminated soil.

The Blood Always Suffers Too

The long-term effects did not stay in the mine. They crept into the bodies of families, into the bloodstreams of children born years later.

Health clinics nearby lacked the resources to diagnose radiation exposure. Most villagers never knew the source of their pain. There were no compensation programs. No formal studies to track disease clusters. No global headlines.

Environmental damage also became clear. Crops grown near the old mine site often failed. Wildlife disappeared from nearby forests. The soil remained radioactive in some areas decades after the last official extraction.

In 2004, the Congolese government issued a presidential decree banning all mining in and around Shinkolobwe. Despite this, illegal mining still occurs, driven by poverty and desperation. Cobalt and copper are in global demand. People risk exposure for a chance at survival.

Today, the scars remain. Radiation lingers, and communities live in poverty. The mine may be quieter now, but its legacy is not. It lives on in sick bodies, polluted land, and unanswered questions.

More Articles from this Publisher

1986 Cameroonian Disaster : The Deadly Cloud that Killed Thousands Overnight

Like a thief in the night, a silent cloud rose from Lake Nyos in Cameroon, and stole nearly two thousand souls without a...

The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb

The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb.

Why A Company's Networth Doesn't Predict Success in Africa

There’s a familiar buzz every time an African startup announces a big funding round—“$80 million secured!” It feels like...

Why Hustle Culture Kills Career Growth in Africa

Is your future really safe with hustle?

LuisaViaRoma Shakes Up Business: CEO Reveals Major Restructuring & Milan Unit Closure

LuisaViaRoma is undergoing a major reorganization, including the closure of its Milan office, to streamline operations a...

Border Breakthrough: Singapore & Malaysia Unveil High-Speed RTS Link, Redefining Cross-Border Travel

The first train for the Singapore-Malaysia Rapid Transit System (RTS) Link has been unveiled, marking a pivotal step tow...

You may also like...

1986 Cameroonian Disaster : The Deadly Cloud that Killed Thousands Overnight

Like a thief in the night, a silent cloud rose from Lake Nyos in Cameroon, and stole nearly two thousand souls without a...

Beyond Fast Fashion: How Africa’s Designers Are Weaving a Sustainable and Culturally Rich Future for

Forget fast fashion. Discover how African designers are leading a global revolution, using traditional textiles & innov...

The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb

The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb.

TOURISM IS EXPLORING, NOT CELEBRATING, LOCAL CULTURE.

Tourism sells cultural connection, but too often delivers erasure, exploitation, and staged authenticity. From safari pa...

Crypto or Nothing: How African Youth Are Betting on Digital Coins to Escape Broken Systems

Amid inflation and broken systems, African youth are turning to crypto as survival, protest, and empowerment. Is it the ...

We Want Privacy, Yet We Overshare: The Social Media Dilemma

We claim to value privacy, yet we constantly overshare on social media for likes and validation. Learn about the contrad...

Is It Still Village People or Just Poor Planning?

In many African societies, failure is often blamed on “village people” and spiritual forces — but could poor planning, w...

The Digital Financial Panopticon: How Fintech's Convenience Is Hiding a Data Privacy Reckoning

Fintech promised convenience. But are we trading our financial privacy for it? Uncover how algorithms are watching and p...