The Mysterious Disease: How Smallpox Empowered a Tricky Cult in Nigeria

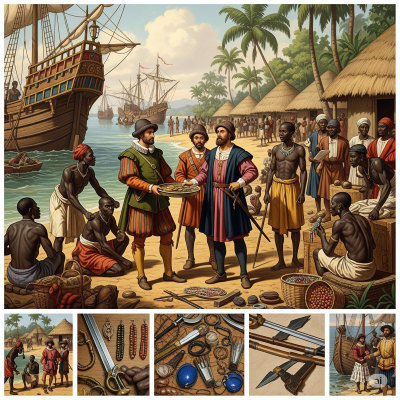

Chapter 1: Unexpected Exchanges

By the late 15th century, West Africa was deeply connected to regional and trans-Saharan trade networks. The coastal kingdoms — including Benin, Oyo, and various Ijo and Igbo communities — were already established, with political systems, organized religion, military capacity, and international commerce.

Around this time, Portuguese sailors became the first Europeans to establish sustained contact with the region. They came seeking gold, ivory, and eventually labour, and by the 1470s, they were anchoring ships along the coast of what is now Nigeria.

These early interactions opened the door to new trade — and to new biological andspiritual nightmares.

A New Strain Enters

Smallpox was not new to Africa. Old records and findings show that a kind of smallpox virus had been in some parts of Africa for hundreds of years. But the type of smallpox that appeared in coastal West Africa in the 1500s was different. It came with Portuguese sailors, traders, and returning enslaved people.

In Portugal, by contrast, smallpox had long been endemic. The disease was so common that most children caught it before age ten. While still deadly, its effects were somewhat blunted by partial immunity in the Portuguese population.

In Africa, where people had never been exposed to this strain before, up to 30 out of 100 people who got it could die.

What the Disease Looked Like

Smallpox crept in like a shadowy predator stalking its prey. First, it whispered through the body—a sudden blaze of fever that scorched the skin, bones aching as if crushed beneath an invisible hammer, waves of exhaustion dragging the soul into darkness, and relentless storms of gut twisting vomit. Then, as if the body itself betrayed its host, a sinister rash erupted like a cruel artist’s canvas—first painting the face and mouth with fiery, angry boils, then spreading like wildfire across arms, chest, and legs.

These cruel marks bubbled with dark, venomous fluid before hardening into jagged, lifeless scabs — a mask of torment that some wore forever. Survivors bore the scars like ghostly reminders etched deep into their flesh, and for others, the disease stole away their sight, plunging them into eternal darkness.

Chapter 2: The Association With a Deity

Before modern medicine, responses to smallpox varied across regions. In parts of West Africa, traditional healers used herbal treatments and isolation practices to manage symptoms. In Yoruba-speaking areas, smallpox was closely associated with the spiritual force Ṣọ̀pọ̀na, who was both feared and honored.

Remedies often combined medicinal plants, ritual practices, and social measures, such as temporary quarantines. In some communities, families would mark infected homes and avoid contact until the illness had passed. These responses weren’t always effective at stopping outbreaks, but they reflected a structured understanding of disease and contagion.

As the disease spread inland, it reached the Yoruba people, who lived in the city-states of Ife, Oyo, and Ogbomosho. The Yoruba, with their rich spiritual traditions, interpreted the outbreak through their religious lens.

They believed that smallpox was a manifestation of the wrath of Ṣọ̀pọ̀na, the god of smallpox. Worship of Ṣọ̀pọ̀na was highly controlled, with specific priests in charge of shrines dedicated to the deity. These priests were believed to have the power to cause and cure smallpox outbreaks. The Yoruba people, in their fear and reverence, turned to these priests for protection and healing.

Chapter 3: The Rise of the Sopona Worship

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Over time, the worship of Ṣọ̀pọ̀na evolved from scattered fear into a deeply entrenched institution. The Ogboni society—a secretive and powerful Yoruba fraternal order—emerged as the hidden guardians of the cult’s secrets. Their influence extended far beyond religion, shaping political power and social order. Among their ranks were keepers of ancient knowledge, including the mysterious rituals tied to smallpox.

These priests claimed a chilling authority: the ability to unleash or contain smallpox outbreaks at will. For the desperate people, caught between the horrors of the disease and the grip of tradition, the priests became both feared oppressors and indispensable protectors. In their eyes, only Ṣọ̀pọ̀na’s custodians could shield them from devastation—binding communities to a fragile and dangerous trust.

Chapter 4: The Arrival of Dr. Oguntola Sapara

In the shadowy streets of late 19th-century Lagos, a man walked a dangerous path few dared to tread. Oguntola Sapara—born Alexander Johnson Williams in Sierra Leone and one of the first Western-trained Nigerian doctors—had returned home after studying medicine in Europe. Appointed Assistant Colonial Surgeon in 1896, Sapara quickly confronted a terrifying reality: smallpox was ravaging communities, but something far more sinister lurked beneath the surface.

Whispers spoke of the Ṣọ̀pọ̀na cult, feared for their mysterious power over disease and death. Sapara’s instincts told him the priests were no mere bystanders—they were orchestrating the epidemic itself. To expose this dark secret, he took an unimaginable risk. Disguised as a devoted initiate, Sapara infiltrated the cult’s hidden ceremonies, witnessing chilling rituals that blurred the line between faith and malevolence.

What he uncovered was shocking: the priests were deliberately using infected materials to spread smallpox, weaponizing fear and sickness to maintain their grip on power. With this explosive revelation, Sapara faced a harrowing choice—would the colonial authorities believe him, and could they stop a deadly conspiracy that threatened to consume an entire nation?

Chapter 5: The Colonial Response

In 1907, based on Sapara's revelations, the British colonial government banned the public worship of Ṣọ̀pọ̀na. This was a significant blow to the Ogboni society and their control over smallpox outbreaks. However, the disease had already taken a firm hold in the region.

The British introduced vaccination campaigns using calf lymph from the British Lister Institute. These campaigns faced resistance, particularly in the northern regions where traditional beliefs were deeply rooted. The vast size of the Northern Province and inadequate health resources compounded the challenge.

Despite these obstacles, the vaccination efforts continued, and over time, smallpox cases began to decline.

Chapter 6: The Final Battle

In the 1960s, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched an intensified smallpox eradication program. Nigeria, a key player in West Africa, was at the forefront of this global effort. However, the outbreak of the Biafran Civil War in 1967 posed a significant challenge.

Remarkably, health officials from both the Nigerian government and the secessionist Biafran forces continued to collaborate during the war. Temporary ceasefires were arranged to allow vaccination teams to operate and to transport vaccines and patients between the two regions.

Despite the turmoil, the eradication program made significant progress. By 1970, smallpox was declared eradicated in Nigeria, marking a significant victory in the global fight against the disease.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

The story of smallpox in Nigeria is one of cultural conflict, scientific discovery, and resilience. It highlights the intersection of traditional beliefs and modern medicine, and the lengths to which individuals went to protect their communities. Today, smallpox remains the only human disease to have been eradicated through vaccination. The lessons learned from Nigeria's experience continue to inform public health strategies worldwide.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...