The Bini Empire Had Streetlights Before London: What We Were Before We Were Colonized

When we were in primary school, we were taught that Africa was “discovered.” That we were nothing until ships arrived. That civilization began the day some white man planted a flag on our soil. That our history was in darkness, until the light of the West arrived.

But the thing about history is that it has a way of blinking at you when you finally open your own eyes.

Like when I accidentally heard from a radio programme that the Benin (or Bini) Empire had streetlights before London. Arranged along the city’s broad, clean roads were palm oil lamps that lit at night to guide residents of the Oba’s great city.

I remember being so shocked and perplexed, then almost crying. Because I realized something so simple yet so tragic: we had light. We had order and glory. And we had it long before colonizers came with their “civilization.”

A City of Walls and Wonders

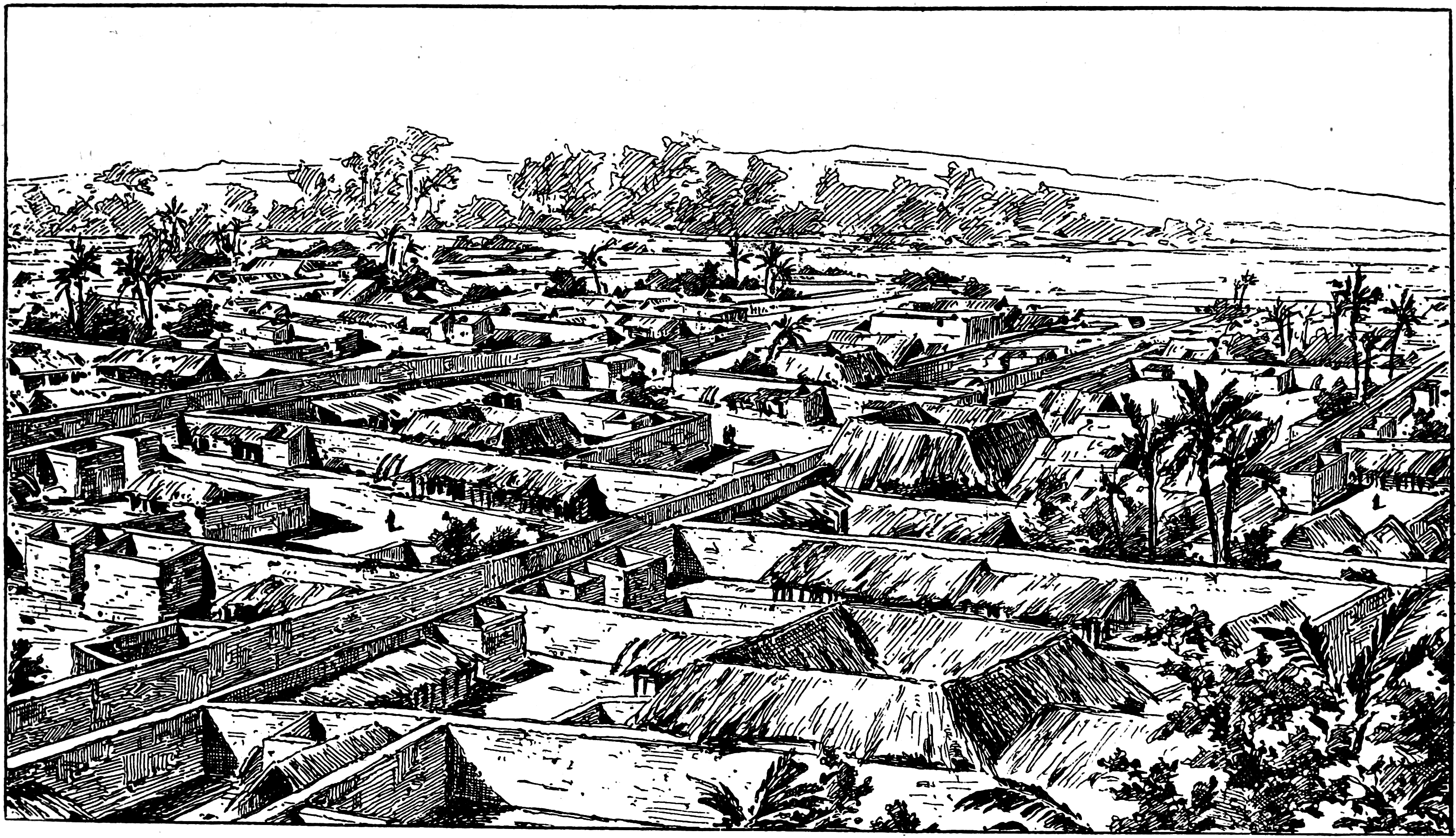

Let’s travel back in time: Benin City, not the modern-day capital of Edo State, but the ancient kingdom it once was, stood as one of the most sophisticated cities in the pre-colonial world.

According to early Portuguese explorers in the 15th century, it was “as well laid out as Amsterdam,” complete with neatly arranged streets, expansive moats, and massive walls that, taken together, are considered one of the largest man-made earthworks in history.

Think about that. While most of Europe was still fumbling through feudalism and bubonic plagues, the Bini people had already mastered urban zoning, with streets wide enough to accommodate traffic and spaces carefully divided for residences, markets, palaces, and spiritual centers. The Oba’s palace was a marvel, sprawling, majestic, and guarded by art, myth, and protocol.

This was not a loose collection of huts. This was a planned city. A living, breathing political and cultural engine. And it shone brightly.

Photo Credit: X

The Myth of Darkness

The palm oil lamps that lined major streets were not just decorative; they were symbolic. It served as a physical embodiment of order, protection, and prestige.

Elders still tell tales of how the streets glowed golden under the flicker of oil-powered lamps long before the first lightbulb came into existence in the West.

Contrast that with London, which didn’t install public street lighting until the 1700s, and even then, it was faint and gas-powered. Before that existed darkness and danger after dusk.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

But somehow, we are the ones remembered as "living in the dark."

This misremembering is not accidental. It is well-engineered. The colonial textbooks taught us to see Europe as our saviour and Africa as a wild, waiting land.

It is in the missionary stories that cast African religions as demonic and European Christianity as salvation. It is in the very phrase “before colonization,” which is used to imply a blank canvas when in fact, it was a canvas rich with colour, complexity, and creativity.

Politics, Power, and Precision

The Benin Empire was not just visually impressive; it was politically advanced. At its center was the Oba, not a dictator, but a monarch working within a system of carefully balanced powers. Everyone had a role; from the Uzama (kingmakers) to the Ogisos before them to the town chiefs and the guilds.

And speaking of guilds, the Bini were perhaps one of the earliest examples of specialized labour systems. We can find bronze casters, carpenters, ivory workers, spiritualists, war captains etc. Each group had clear functions, leadership, and rules. These were not just jobs, they were well established institutions.

It was a government, an economy, and a social order, long before Britain figured out how to file taxes properly.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Art That Told the Truth

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the Benin Empire is its art. The Benin Bronzes — now scattered in European museums after being looted during the 1897 British Punitive Expedition — are not just beautiful, they are historical records.

They document royal lineages, ceremonies, wars, beliefs, and social structures in such intricate detail that art historians still gasp at their technical mastery.

And yet, many Nigerians only learned about these bronzes when the conversation around restitution began. How tragic.

We should have grown up seeing them, understanding them, and drawing strength from them. Instead, we saw them behind glass, in institutions that claimed to be “preserving” them from us, protecting them from the same people who birthed them.

The Invasion That Tried to Erase Us

In 1897, the British Empire, under the guise of trade and diplomacy, launched a brutal assaulton Benin City. They burned it, looted it, desecrated sacred spaces, killed civilians and exiled the Oba.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

And then, as though destruction was not enough, they rewrote the story. Suddenly, Benin was not a shining city — it was a primitive backwater that needed taming. A place of "barbaric rituals" and "tribal wars." The city of light was recast as a jungle of darkness.

But even after the fire and the lies, fragments of greatness remain. The Oba's descendants still sit on the throne, upholding tradition in the face of modern confusion. The Igue Festival is still celebrated. The guilds still train new hands. And the people of Benin still walk streets where history hums just beneath the surface.

What We Lost And What We Still Carry.

The colonization of Benin was not just physical; it was psychological. We lost not only artefacts and land but also confidence. The belief that we were enough. The belief that our systems, our faiths, our philosophies, and our ways of life were valid.

And yet, even after centuries of being told we were nothing before colonization, the facts keep leaking through. Facts that tell a different story:

We had cities with better sanitation than those in 17th-century Europe.

That we had art so advanced it baffled European critics who thought Africans couldn’t possibly have made it.

That we had light before those who claimed to bring it to us ever lit a single streetlamp of their own.

Reclaiming the Narrative

Today, the movement to return the stolen Benin Bronzes is part of a larger project of reclaiming the African narrative. We are finally telling our stories not as footnotes in someone else’s history, but as chapters of human achievement.

We are insisting that history begins here, too. Before Lagos, there was Benin. Before skyscrapers, there were moats and masterpieces.

Before colonization, there was a light that burned brightly, not because it came from Europe, but because we lit it ourselves.

So the next time someone tells you that Africa was “discovered,” correct them.

Tell them about the palm oil lamps. Tell them about the moats. Tell them about the bronzes.

Tell them about the empire that glowed in the dark, way long before the West even knew where to look.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Because we were not waiting in the shadows for the world to find us. We were lit.

Recommended Articles

There are no posts under this category.You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...