Rez: K. Antweiler: Memorialising the Holocaust in Human Rights Museums

Katrin Antweiler’s “Memorialising the Holocaust in Human Rights Museums” captures the global proliferation of museums that seek to teach the lessons of the past, namely the Holocaust, in order to strengthen a culture of human rights and democracy in the present. Antweiler calls this intersection the “Holocaust-human rights nexus,” which she argues seeks to shape visitors into “historically aware human rights advocates” vis-a-vis a Western (European) neoliberal concept of democracy. While Holocaust and memorial museums are well-covered in the scholarly literature and there is a growing body of research on human rights museums, Antweiler adds an important new dimension. She interprets the work of these museums using Foucault’s concept of governmentality, demonstrating how the booming field of global Holocaust-human rights education in spaces like museums is deeply political and is ultimately intended to maintain the neoliberal status quo.

The book is based on an analysis of three case studies, Germany’s Memorium Nuremberg Trials, the Canadian Museum of Human Rights (CMHR) and the Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Center (JHGC), but it is Antweiler’s extensive theoretical framework, laid out in the first four chapters out of ten, that is perhaps most critical to her analysis. In chapters one and two, she interweaves literature from memory and decolonial/postcolonial studies with Foucault’s concepts of governmentality and “techniques of the self” to lay out her argument that public memory – such as that found in human rights and Holocaust museums – is a “discourse of knowledge” (p. 49) that ultimately “prop[s] up modes of coloniality” (p. 56). In chapters three and four, she traces the emergence and global spread of Holocaust memory, human rights discourses and global education around human rights, demonstrating the emergence of the Holocaust-human rights nexus as a mode of governmentality that tends to not only avoid sustained engagement with the causes and effects of the historic events (p. 68), but also places the burden of responsibility – both for the violence and for the promotion and maintenance of human rights – on the individual, rather than acknowledging the systemic, structural causes and ongoing consequences of violence. In this way, Antweiler not only critiques Holocaust and human rights education but also, and especially, how within the neoliberal project “memory politics might uphold racial and colonial power structures” (p. 211).

In chapters five through seven, Antweiler presents “biographies” of her case studies, giving social and political context for each museum and presenting the “emplotment of Holocaust memory into the [museum’s] story of progress towards the rule of law and a human rights culture” (p. 163). The first case study, Memorium Nuremberg Trials, differs from the others in that it is located at the historic site of the International Military Tribunal and tells a relatively narrow story of the trials, which did not actually address the Holocaust (or genocide) as such. It is also conceived as a documentation center that avoids an “emotive” approach to storytelling, which is very different from other Holocaust and memorial museums around the world, including the other two case studies. While these divergences make it an interesting, if sometimes puzzling, case to include, Antweiler demonstrates how the museum presents an “over simplified transition from Nazism to a culture of human rights” (p. 100) that comports with her overarching critique of the Holocaust-human rights nexus’ teleological lesson: as Antweiler writes in her conclusion, in these museums the “narrative of human rights only has one possible ending, which is liberal democracy” (p. 210).

The second case study, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, is the only of Antweiler’s cases that explicitly refers to itself as a human rights museum. As a national, “ideas” museum, the CMHR takes a universal approach to exhibiting the concept of human rights and laying out not only historical examples of human rights abuses, but also a call to action for individual visitors to protect and promote human rights. However, the museum was initially conceived as a Holocaust museum and an exhibit on the Holocaust is its centerpiece. Presenting the Holocaust as an extreme case of the cost of human rights “neglected” (p. 126), the exhibit also suggests teleological progress in that the Holocaust led to the UN Declaration on Human Rights. Further, this emphasis on the Holocaust-human rights nexus allows the CMHR to avoid confrontation with Canada’s own human rights violations vis-a-vis its Indigenous populations, both in the past, such as in the residential boarding schools, and present.

The final case study, the Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Centre similarly uses the Holocaust as “entry point” to difficult issues closer to South Africa’s own history, not just apartheid, but ongoing inequality and economic and structural violence (p. 152). The JHGC also draws parallels between the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide, demonstrating the costs of ignoring the Holocaust’s historical lessons that should have been learned by the international community. In many ways, because South Africa a relatively new democracy, the JHGC places a stronger emphasis on “citizenship education” in the effort to strengthen and sustain the nascent democratic society (p. 153). But like the other two case studies, the intersection of the Holocaust and human rights education in South Africa demonstrates that it is generally much easier to critique other nations than one’s own, and easier to critically engage a more distant history than the recent past or present.

Through these case studies, Antweiler introduces the compelling concept of “exhibitionary atonement [...] which suggests that it’s possible to make up for past wrongs by simply putting them on public display” (p. 131). Certainly the proliferation of Holocaust and memorial museums around the globe suggests that there is a deep-seated belief in the notion of exhibitionary atonement. However, perhaps the most critical contribution of Antweiler’s work is her sharp reminder, supported by a strong theoretical foundation, that very often this kind of attempt at “morally charged closure [...] pointing us in the direction of universal human rights” (p. 210) actually forestalls the kinds of questions, confrontations and unsettlement that might actually contribute to dismantling structures of colonialism, inequality and violence that continue to marginalize and oppress sweeping portions of the world’s population today. Rather, the Holocaust-human rights nexus in museums like those analyzed by Antweiler “does not intend to fundamentally change the worlds we live in” (p. 208), but to shore up neocolonial liberal democracy and its “(global) power relations” (p. 209).

As much as I agree with Antweiler’s critical assessment of the global proliferation of Holocaust memory and human rights education, as I watch the democratic backslide in the US (and around the globe) and the sharp turn toward a “post-human rights age,” I find myself second guessing our scholarly rush to condemn liberal democracy. As the current Trump administration politicizes and weaponizes antisemitism in the service of its illiberal agenda, whitewashes US history in cultural institutions, undoes societal efforts to right historical wrongs, and dismantles democratic institutions, the neoliberal “prescriptive visions for the future” Antweiler describes (p. 208) seem quaint and relatively benign. Nevertheless, in the midst of these rapid and frightening societal upheavals, Antweiler’s groundbreaking work gives us an excellent conceptual framework for analyzing future, possibly illiberal, iterations of memorial, human rights and other museums that seek to teach the lessons of past violence in the service of governability and citizenship education.

You may also like...

Diddy's Legal Troubles & Racketeering Trial

Music mogul Sean 'Diddy' Combs was acquitted of sex trafficking and racketeering charges but convicted on transportation...

Thomas Partey Faces Rape & Sexual Assault Charges

Former Arsenal midfielder Thomas Partey has been formally charged with multiple counts of rape and sexual assault by UK ...

Nigeria Universities Changes Admission Policies

JAMB has clarified its admission policies, rectifying a student's status, reiterating the necessity of its Central Admis...

Ghana's Economic Reforms & Gold Sector Initiatives

Ghana is undertaking a comprehensive economic overhaul with President John Dramani Mahama's 24-Hour Economy and Accelera...

WAFCON 2024 African Women's Football Tournament

The 2024 Women's Africa Cup of Nations opened with thrilling matches, seeing Nigeria's Super Falcons secure a dominant 3...

Emergence & Dynamics of Nigeria's ADC Coalition

A new opposition coalition, led by the African Democratic Congress (ADC), is emerging to challenge President Bola Ahmed ...

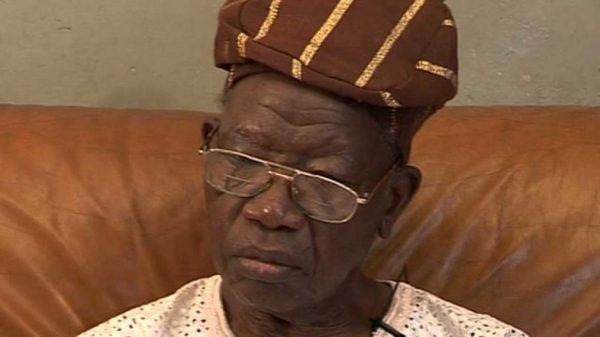

Demise of Olubadan of Ibadanland

Oba Owolabi Olakulehin, the 43rd Olubadan of Ibadanland, has died at 90, concluding a life of distinguished service in t...

Death of Nigerian Goalkeeping Legend Peter Rufai

Nigerian football mourns the death of legendary Super Eagles goalkeeper Peter Rufai, who passed away at 61. Known as 'Do...