Report Details 'Trump's New Lair' Inside the Oval Office

The world has frequently encountered demagogues and fools, yet often, the responses have matched the challenges. In 1990, during his global thank-you tour, President Nelson Mandela, when questioned in Harlem, New York, about his friendships with Muammar Gaddafi, Yasser Arafat, and Fidel Castro, asserted South Africa's autonomy in choosing its allies. He emphasized their support during South Africa's struggles and refused to betray them, earning a standing ovation. Similarly, when British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher advocated for "constructive engagement" to dismantle apartheid, President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, in 2004, countered her duplicity by highlighting how "constructive engagement" primarily benefited England, implicating Thatcher's son, Mark, in continental gunrunning and coup plots, leaving Thatcher without a response.

Fidel Castro famously accused President George Bush of possessing a "pirate mentality." This was not a flippant remark. Illustrating this, Joseph Desire Mobutu, one of Africa’s most notorious kleptocrats with an estimated worth of $5 billion in the 1980s, received a warm welcome from President Bush in 1989. Despite Mobutu's egregious record, Bush publicly lauded Zaire as one of America’s oldest friends and Mobutu as one of its most valued, a sentiment Martin Meredith captured in 'The Fate of Africa.' Echoing Castro's intolerance for foolishness, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo once memorably challenged BBC HARDtalk anchor Stephen Sackur, asking if Sackur would dare pose a similarly perceived rude question to his own prime minister.

There is a considerable history of leaders who have confronted bullies unflinchingly. However, this crucial quality, now more in demand than ever, appears to be diminishing, as evidenced by recent high-profile encounters at the White House since President Donald Trump’s second term. The White House, particularly the Oval Office, has transformed into a metaphorical lion’s den for visiting dignitaries. Following Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s tense exchange with Trump, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa became the latest to face this challenging environment.

From the outset of Ramaphosa's visit, it was evident that Trump had a singular agenda. He showed no interest in resetting trade negotiations, addressing bilateral concerns, mending US-South Africa relations, or understanding alternative perspectives on the alleged genocide against white farmers. Trump was not interested in conciliation; his sole aim appeared to be to dominate and metaphorically 'have Ramaphosa for lunch,' an encounter described as painful and difficult to observe.

Trump's disdain for his visitors was palpable. This was demonstrated through actions such as questioning Ramaphosa about how he obtained Trump's phone number, overtly valuing the presence of golfers Ernie Els and Retief Goosen in Ramaphosa's entourage more than the president himself, presenting fake documents to the South African leader, and turning the Oval Office into a cinema while Ramaphosa was still speaking. This treatment made Zelenskyy’s earlier visit seem almost amicable by comparison.

While some contend that the host’s discourteous behavior—berating a guest with false and discredited materials—reflects more negatively on Trump and the US than on Ramaphosa, who maintained his composure and rationality, this view is only partially accurate. Ultimately, Ramaphosa bears significant responsibility for the shambolic treatment he received, largely for having ignored numerous prior warnings, or 'yellow flags'.

These warnings were abundant: an Executive Order in February halting all US financial aid to South Africa, accusations of “white genocide,” the expulsion of Ambassador Ebrahim Rasool, and the offer of “refugee” status to white farmers. Trump, reportedly influenced significantly by Elon Musk, had consistently displayed his misguided animosity towards South Africa. Additionally, South Africa’s decision to take Israel to the International Court of Justice over the Gaza war and its prominent role in BRICS, which potentially threatens the dollar's influence, were unspoken catalysts for Trump’s anger. Given these clear indicators, Ramaphosa's decision to proceed with the visit, armed with a golfing picture book as a peace offering instead of a more symbolic gesture like a luxury Boeing 747 jetliner, seemed ill-advised.

Despite the evident diplomatic fallout, President Ramaphosa described the visit as “a great success.” This assessment might only hold true if interpreted as a narrow escape from further humiliation. There has been no official confirmation or evidence of the “reset” Ramaphosa had sought. Disturbingly, a fake video depicting crosses on a roadside, purported to be memorials for approximately 1,000 murdered white South African farmers, continued to circulate on the White House’s X handle, indicating no change in stance. Ramaphosa’s optimistic portrayal of the visit has sharply divided opinions within his own country and across a largely subdued African continent.

Femi Badejo, a diplomat and Professor of Political Science, employed a safari metaphor to illustrate the continent's reaction: “If a lion grabs an antelope, what do you think will happen to the rest of the herd?” South Africa is not merely another African nation; it is a leader. Although many African diplomats publicly frame Ramaphosa’s visit as measured and dignified, privately, they are alarmed by the potential implications for themselves and the continent, particularly with the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) set to expire in September.

For various reasons, predominantly economic, the Africa that once resolutely stood up to bullies or was considered a worthy ally seems to be a relic of the past. While leaders like Egypt's Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi might still receive ceremonial welcomes at the White House due to their strategic importance, and figures like Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traore, perceived as a Russian ally, might be feted in the Kremlin, others are left to fend for themselves. Grappling with internal security threats, widespread discontent, and fragile economies, these nations navigate a hostile and deeply polarized world. It may be a considerable time before another African leader ventures to the White House, assuming Trump hasn't already closed half of the US embassies in Africa within his first year in office. If African leaders cannot find solidarity among themselves during these challenging times, they might be better served by remaining at home.

Recommended Articles

Madagascar : Antananarivo hopes for Washington reprieve on AGOA and customs tariffs

After submitting his counter-proposal to the US Department of Commerce, Minister David Ralambofiringa hopes that the dea...

Trade Minister calls for renewal of AGOA due to expire September

The Minister of Trade and Agribusiness, Mrs Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, has called for the renewal of the African Growth a...

Ghana to renew AGOA agreement with USA amid 10% import tariffs

The Minister of Trade, Agribusiness and Industry, Elizabeth Ofosu-Adjare, has made a passionate appeal for the renewal o...

Ghana engages US on AGOA renewal, tariffs and trade balance amid 'America First' push

Ghana has affirmed its commitment to strengthening economic cooperation with the United States, as Trade, Agribusiness a...

Ghana engages US on AGOA renewal, tariffs and trade balance amid 'America First' push | Ghana News Agency

Accra, June 9, GNA – Ghana has affirmed its commitment to strengthening economic cooperation with the United States, as ...

You may also like...

1986 Cameroonian Disaster : The Deadly Cloud that Killed Thousands Overnight

Like a thief in the night, a silent cloud rose from Lake Nyos in Cameroon, and stole nearly two thousand souls without a...

Beyond Fast Fashion: How Africa’s Designers Are Weaving a Sustainable and Culturally Rich Future for

Forget fast fashion. Discover how African designers are leading a global revolution, using traditional textiles & innov...

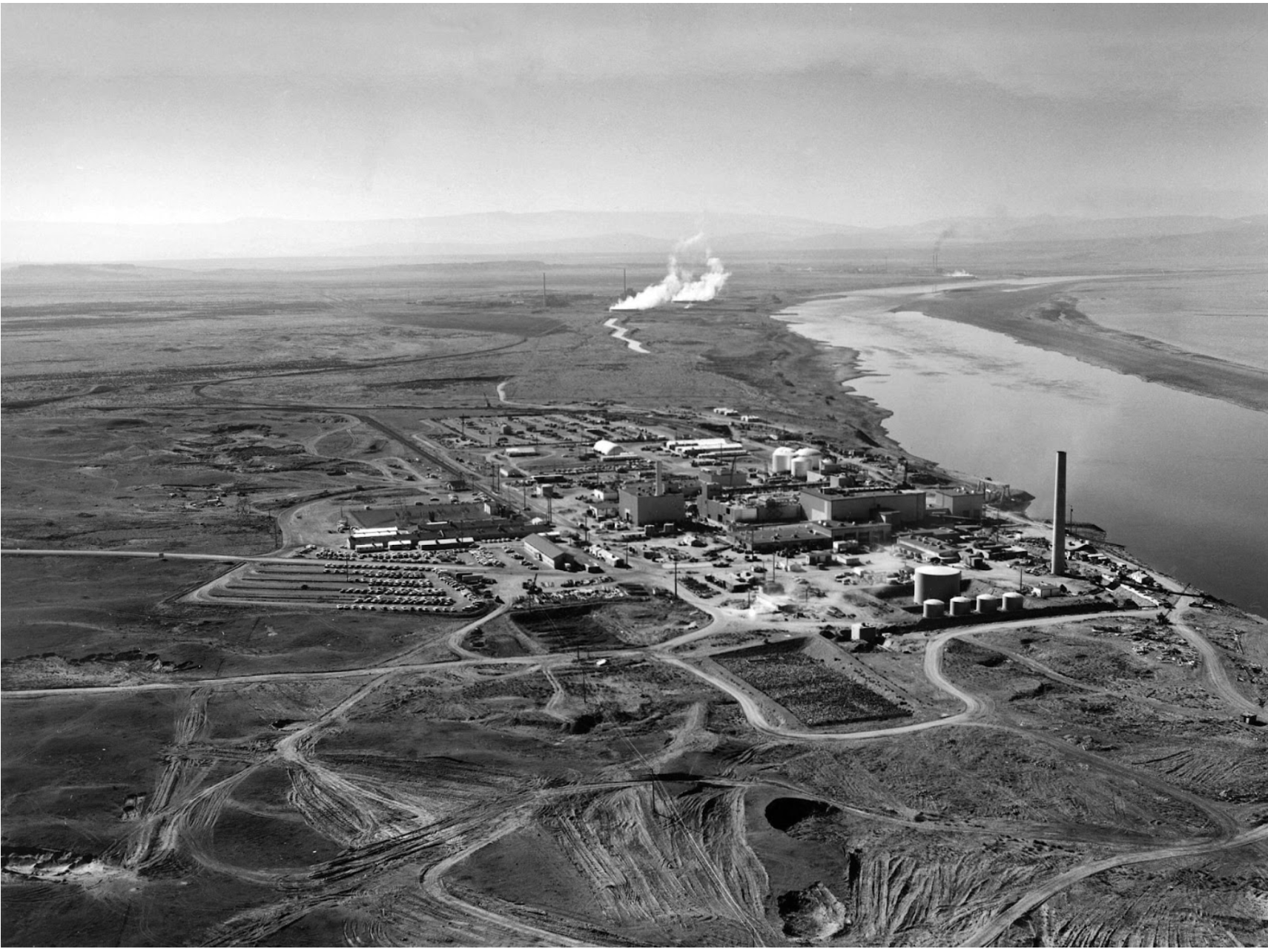

The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb

The Secret Congolese Mine That Shaped The Atomic Bomb.

TOURISM IS EXPLORING, NOT CELEBRATING, LOCAL CULTURE.

Tourism sells cultural connection, but too often delivers erasure, exploitation, and staged authenticity. From safari pa...

Crypto or Nothing: How African Youth Are Betting on Digital Coins to Escape Broken Systems

Amid inflation and broken systems, African youth are turning to crypto as survival, protest, and empowerment. Is it the ...

We Want Privacy, Yet We Overshare: The Social Media Dilemma

We claim to value privacy, yet we constantly overshare on social media for likes and validation. Learn about the contrad...

Is It Still Village People or Just Poor Planning?

In many African societies, failure is often blamed on “village people” and spiritual forces — but could poor planning, w...

The Digital Financial Panopticon: How Fintech's Convenience Is Hiding a Data Privacy Reckoning

Fintech promised convenience. But are we trading our financial privacy for it? Uncover how algorithms are watching and p...