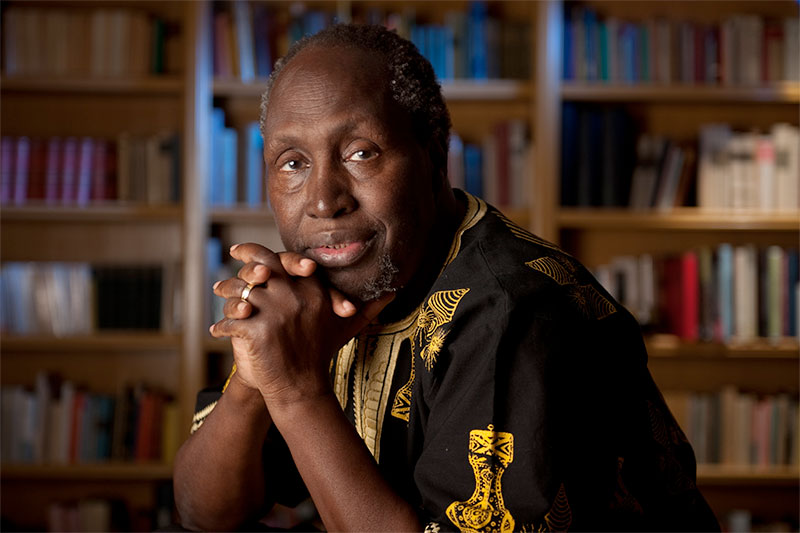

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: A Name History Won't Erase

Authors: Owobu Maureen & Ibukun-Oluwa Addy

Long before he became a literary giant, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was just a barefoot boy in rural Kenya, watching history unfold in the rustling of banana leaves and the whispers of war. Born on January 5, 1938, in Kamiriithu village, central Kenya, Ngũgĩ was the fifth child of his mother, Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ, one of his father’s four wives. His father, Thiong’o wa Nducu, was a farmer: strict, polygamous, and deeply rooted in Gikuyu traditions. No wonder Ngũgĩ was one of more than 20 children in their large, extended household.

Ngũgĩ’s world was split in two: the communal life of his ancestral village, full of oral storytelling, and the encroaching reality of British colonialism, which threatened to erase those very stories. Kenya was under British rule, and Ngũgĩ came of age during the turbulence of the Mau Mau uprising—a rebellion led by native Kenyans resisting colonial oppression and land seizure. That experience of cultural conflict, colonial violence, and identity crisis would become the spine of his life’s work.

Before the Spotlight: The Making of a Mind

Before the world knew his name, Ngũgĩ was a curious, observant child with a deep hunger for knowledge. Encouraged by his mother, who once told him to “go to school, even on an empty stomach,” he took education seriously—not as a path to privilege, but as a form of survival.

He attended Alliance High School, a prestigious missionary school where Shakespeare was sacred and African names were discouraged. There, he encountered English literature—Dickens, Shakespeare, the Bible—but also the alienation of a system that demanded the abandonment of African identity.

After high school, he went on to Makerere University in Uganda, one of East Africa’s intellectual powerhouses at the time. It was there, amid a wave of post-independence African consciousness, that Ngũgĩ began to write and interact with other young African intellectuals and writers. He later pursued postgraduate studies at the University of Leeds in the UK.

A Young Writer Steps Forward

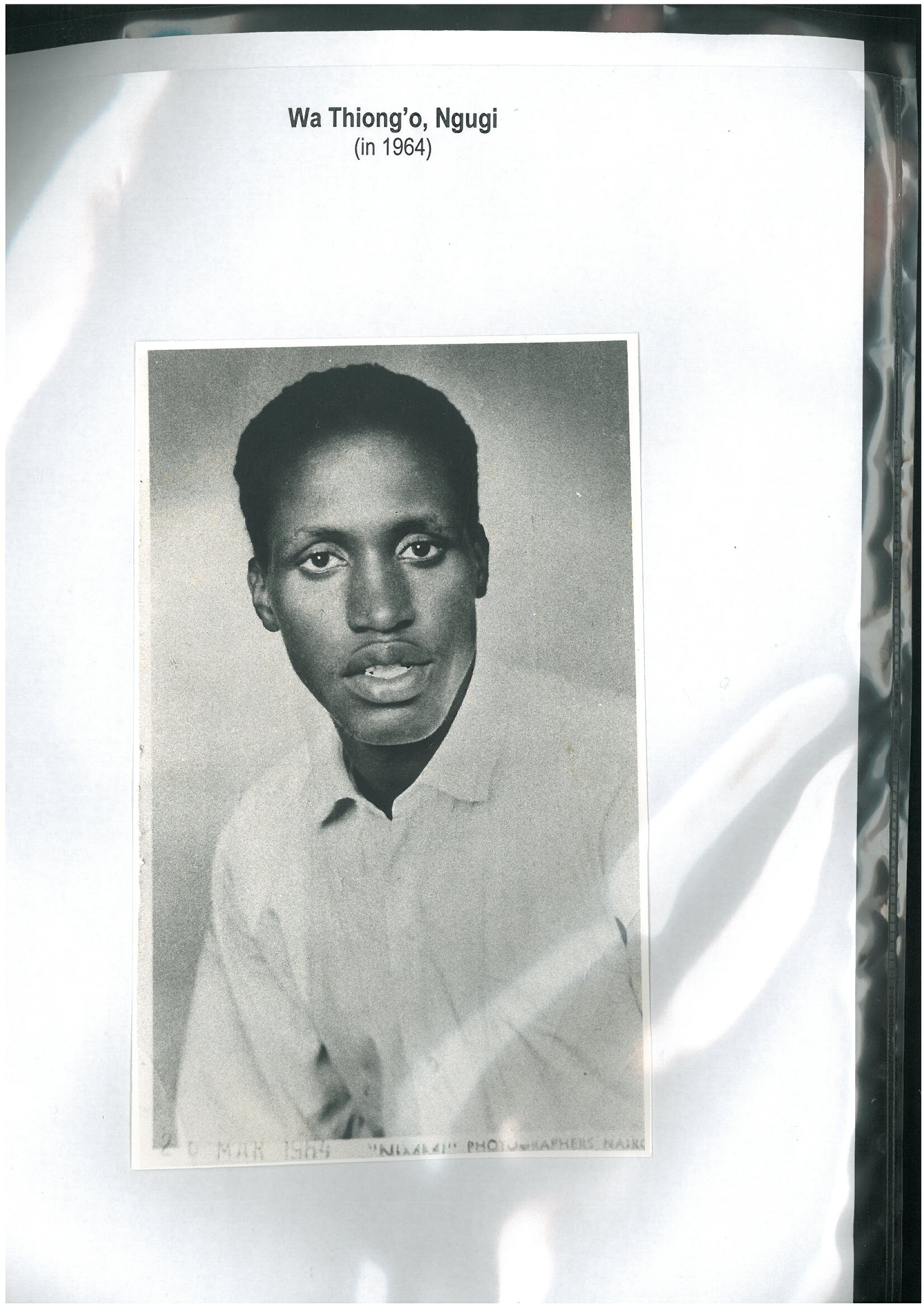

In the early 1960s, a young James Ngugi (as he was still known) sharpened his voice as a writer. His first major success came in 1964 with the publication of Weep Not, Child—the first English-language novel by an East African author. He was just 26.

The novel told the story of a boy growing up in colonial Kenya, caught between education, tradition, and the looming shadow of resistance. It was autobiographical, lyrical, and revolutionary. The world took notice.

He followed it with The River Between (1965), which explored tensions between Christianity and Gikuyu traditions, and A Grain of Wheat (1967), a powerful narrative about betrayal and liberation during Kenya’s independence struggle. These early works cemented him as a vital voice in African literature, unafraid to interrogate both colonial brutality and African complicity.

His Greatest Hits: Words That Roared

Ngũgĩ’s literary canon grew rapidly. With novels like Petals of Blood (1977) and Devil on the Cross (1980), he took a sharp turn toward political critique, targeting neocolonialism and the betrayal of independence ideals by African elites. These books weren’t just stories—they were indictments, bold enough to get him imprisoned by the Kenyan government.

His style evolved, too. Initially writing in English, Ngũgĩ made a radical decision in the late 1970s: he would abandon English altogether and write exclusively in Gikuyu, his mother tongue. This was more than a language switch—it was a rebellion against cultural imperialism, a reclaiming of voice.

The Forces That Shaped Ngũgĩ

“The courage of peasants and workers in the face of overwhelming odds,” he once reflected, “became my earliest lesson in the power of ordinary people.”

As a young man, Ngũgĩ’s intellectual world expanded through voracious reading. The works of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Mao Tse Tung offered him a framework for understanding class struggle and oppression. Philosophers like Hegel and novelists such as Tolstoy and Joseph Conrad also shaped his literary sensibilities, blending political urgency with narrative craft.

One of the most memorable facts about Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is that he wrote Devil on the Cross—the first modern novel in the Gikuyu language—on prison-issued toilet paper while incarcerated by Kenyan authorities in 1977. His crime? Co-writing a politically charged play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), which the government banned.

After his imprisonment, Ngũgĩ made the radical decision to no longer write in English. Instead, he embraced his mother tongue, Gikuyu, as an act of cultural reclamation and resistance. “Language, any language, has a dual character: it is both a means of communication and a carrier of culture,” he famously said.

A Global Legacy: Who Ngũgĩ Inspired

Ngũgĩ’s influence radiates far beyond Kenya. Alongside Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, he stands as a pillar of African literature. His insistence on linguistic self-determination inspired a movement among African writers to embrace indigenous languages—a stance that reshaped both literary expression and academic thought.

His works, including his short story The Upright Revolution, have been translated into more than 100 languages, making him one of the most widely translated African authors in history.

Recognition and Honors: A Life Celebrated

Ngũgĩ’s courage and creativity did not go unrecognized. In 2022, he received the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature. He also received the Nonino International Prize for Literature (2001), South Korea’s Park Kyong-ni Prize (2016), and the Catalonia International Prize (2019), among others.

In 2023, the Kenya Theatre Awards gave him the World Impact Award, honoring his literary achievements and groundbreaking playwriting. With 13 honorary doctorates and decades of global acclaim, Ngũgĩ’s legacy is secure, etched in books, in classrooms, and in the minds of readers still dreaming of freedom.

A Legacy Now Complete

On May 19, 2025, the world lost Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o at the age of 87. But his passing marks not an end, but the immortalization of a literary warrior whose pen never rested.

His last major work, Kenda Muiyuru (The Perfect Nine), was a Gikuyu-language epic that earned him a longlisting for the 2021 International Booker Prize, proving that even in his later years, Ngũgĩ never stopped pushing boundaries. It was a lyrical retelling of Gikuyu mythology—and a love letter to African languages, feminist storytelling, and oral traditions.

Ngũgĩ was never just a novelist. He was a cultural insurgent, a literary architect, and a decolonial thinker who saw the shape of power—and challenged it relentlessly. His writings critiqued both colonial and post-colonial regimes, from British brutality to African elites who mirrored the same oppressive systems.

His nonfiction, especially Decolonising the Mind (1986), became a foundational text in post-colonial studies, shaping global conversations about language, identity, and liberation. He fought to dismantle the dominance of English in African discourse and led efforts that saw Kenya’s University of Nairobi replace its English department with a Department of Literature focused on African texts.

Ngũgĩ’s influence stretched across the globe. His works have been translated into over 30 languages. He appeared frequently on lists of Nobel Prize contenders—though he never won, his impact far outshone the absence of that accolade. Even in his final years, he was translating his earlier English works into Gikuyu, restoring what colonization had taken—word by word, story by story.

Ngugi as a student in university, circa 1966

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...