How 1970s Nigerian Newspapers Fought Against Military Censorship

Photo Credit: Punch Newspaper

Picture a newsroom in Lagos, 1974. The clack of typewriter keys punctuates the thick, dusty air. A junior reporter rushes in, a statement in a brown envelope from a “reliable source” in hand. The editor scans it, brows furrowed. The story is explosive, allegations of corruption involving a top military officer.

But before the presses can roll, a phone call comes in from the Ministry of Information. A familiar voice, calm yet laced with menace, instructs: “Drop it. Or else.”

This was the daily reality of Nigerian journalists in the 1970s. This was a decade when military regimes tightened their grip on power and saw the press as both a threat and a tool. Yet, despite decrees, intimidation, and arrests, newspapers fought back, fiercely.

Photo Credit: Google

The Iron Grip of Military Rule

The Nigerian Civil War had ended in 1970, but the country’s political life was far from peaceful. General Yakubu Gowon’s government, and later the short but intense regimes of Murtala Mohammed and Olusegun Obasanjo, were determined to project strength and maintain order.

For the press, “order” often meant silence. A batch of decrees clipped the wings of journalists and the press, at large. Decree No. 11, for instance, protected public officers from “false accusations” which was just a vague phrase that conveniently protected them from any critical reporting.

Sedition laws could land a journalist in prison for stories deemed to “incite disaffection.” Detention without trial was a real and terrifying possibility.

Government-owned outlets like the Daily Times, which was once proudly independent, were increasingly assimilated. Ministries pushed for uniform narratives, particularly on issues of corruption, human rights abuses, or policy failures. In this climate, dissenting voices had to either submit, shut down, or get creative.

The Newspapers That Refused to Bow

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Several papers became known for pushing the limits. The Nigerian Tribune, with its deep ties to southwestern political thought, continued to publish editorials that shook the military authoritarianism. The Punch, a relatively young publication then, adopted a lively, satirical style that disguised critique in humour.

In the north, the New Nigerian often walked a fine line, voicing concerns over governance while avoiding direct confrontation with power. And though the Guardian did not debut until the late 1970s, its founding vision was already brewing. A press that js guided by intellectual rigor and social responsibility.

What united these outlets was not just a desire to report the news, but to defend the right of Nigerians to hear it and that even means taking calculated risks.

Strategies of Resistance

1. Coded Language and Satire

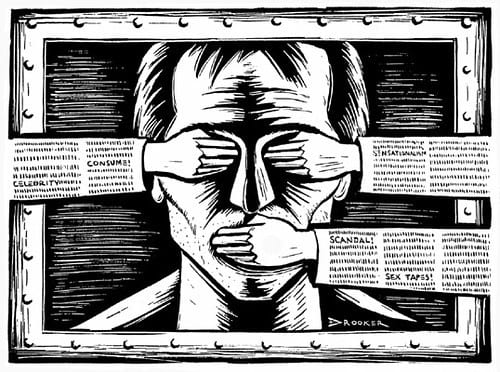

Directly accusing a general of misconduct could earn a swift arrest. Instead, journalists mastered the art of implication. Editorials used fables, proverbs, and allegory which seemed harmless.

You would encounter stories about a “chief in the village” whose “yam barn was mysteriously full” after a poor harvest. Readers understood the subtext.

Political cartoons became weapons of subversion. A single image of a bloated soldier blocking a ballot box could say what 1,000 censored words could not.

2. Playing with Layout

Some editors developed a sly habit: placing a controversial piece next to harmless news. For example, a corruption exposé beside an article on yam prices, making it less likely to be flagged by censors skimming proofs.

Others crafted headlines with double meanings. On the surface, they complied while between the lines, they mocked.

A phrase like “New Era of Discipline” could refer both to the government’s slogan and to the rigid, joyless reality people faced.

3. Editorial Defiance

Certain journalists refused to be subtle at all. Opinion columns boldly criticized policy failures, sometimes using the safety of collective editorial boards to avoid singling out one writer for retaliation. The Nigerian Tribune, for instance, occasionally published fiery editorials that drew direct government warnings but rallied public sentiment.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

4. Underground and Alternative Press

When the military clamped down hardest, shutting down presses or seizing entire editions, alternative networks sprang up. Leaflets and pamphlets circulated through campuses and markets.

These underground publications, often anonymous, could be blunt where mainstream outlets had to be clever. They were the unfiltered whispers of the street, amplified in print.

5. International Leaks

Some journalists quietly passed stories to foreign correspondents from the BBC, Reuters, and The Times of London. Once published abroad, these stories could make their way back into Nigeria to be read over radio, often beyond the reach of local censors.

Photo Credit: Google

Flashpoints and Confrontations

The 1970s were dotted with high-profile clashes between the press and the military.

Journalists faced harassment, arrests, and detentions and sometimes for stories they had not even published, but had edited or approved. Newspapers were suspended for “security reasons,” a catch-all excuse that often meant they had embarrassed the wrong officer.

One infamous episode involved a paper that printed a seemingly harmless piece about food shortages. The government saw it as an insult to its “progress” narrative and ordered the presses stopped. The editors responded by reprinting the article in coded form the next week, tucked into a “letter from a concerned farmer.”

The Public Kept Listening

Despite the constant threats, these acts of resistance had an effect. Ordinary Nigerians learned to read between the lines, interpreting satire and metaphor as fluently as straight reporting.

The public grew more politically literate, understanding that silence in the papers often meant trouble behind the scenes.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

In many ways, censorship sharpened the relationship between journalists and readers. It became a shared puzzle, a game of clues against the backdrop of oppression.

The Legacy of the 1970s Press

When Nigeria returned to civilian rule in 1979, the press had already been tempered by nearly a decade of military intimidation. This resilience would prove crucial during later crackdowns in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly under General Sani Abacha.

The strategies of the 1970s like coded writing, alternative publications, and international alliances, would resurface whenever press freedom came under threat again. The journalists of that era became mentors, teaching younger reporters that truth could survive even in the most hostile climates.

Lessons for Today

In an age when censorship often takes digital forms like blocking websites, flooding social media with propaganda, the lessons from the 1970s remain relevant.

The courage to question power, the creativity to evade suppression, and the solidarity between journalists and their audiences are still the lifeblood of free expression.

Modern reporters in Nigeria and across Africa can look back on this period as proof that even under the harshest regimes, the truth finds ways to leak through.

You may also like...

Explosive Racism Claims Rock Football: Ex-Napoli Chief Slams Osimhen's Allegations

Former Napoli sporting director Mauro Meluso has vehemently denied racism accusations made by Victor Osimhen, who claime...

Chelsea Forges Groundbreaking AI Partnership: IFS Becomes Shirt Sponsor!

Chelsea Football Club has secured Artificial Intelligence firm IFS as its new front-of-shirt sponsor for the remainder o...

Oscar Shockwave: Underseen Documentary Stuns With 'Baffling' Nomination!

This year's Academy Awards saw an unexpected turn with the documentary <i>Viva Verdi!</i> receiving a nomination for Bes...

The Batman Sequel Awakens: Robert Pattinson's Long-Awaited Return is On!

Robert Pattinson's take on Batman continues to captivate audiences, building on a rich history of portrayals. After the ...

From Asphalt to Anthems: Atlus's Unlikely Journey to Music Stardom, Inspiring Millions

Singer-songwriter Atlus has swiftly risen from driving semi-trucks to becoming a signed artist with a Platinum single. H...

Heartbreak & Healing: Lil Jon's Emotional Farewell to Son Nathan Shakes the Music World

Crunk music icon Lil Jon is grieving the profound loss of his 27-year-old son, Nathan Smith, known professionally as DJ ...

Directors Vow Bolder, Bigger 'KPop Demon Hunters' Netflix Sequel

Directors Maggie Kang and Chris Appelhans discuss the phenomenal success of Netflix's "KPop Demon Hunters," including it...

From Addiction to Astonishing Health: Couple Sheds 40 Stone After Extreme Diet Change!

South African couple Dawid and Rose-Mari Lombard have achieved a remarkable combined weight loss of 40 stone, transformi...