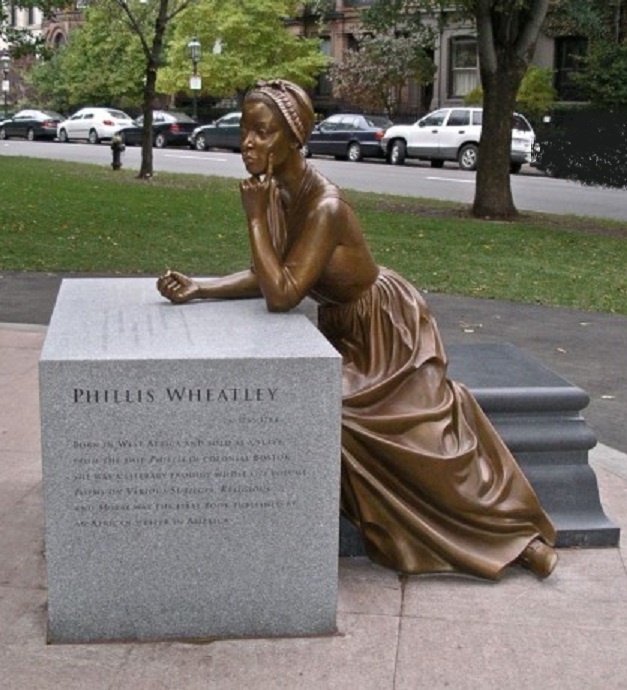

PHILIS WHEATLEY: THE GIRL WHO WROTE HER WAY OUT OF CHAINS

In the shadows of America’s founding years, where liberty was proclaimed from rooftops but denied to the enslaved, one black girl picked up a pen and rewrote her place in history.

Her name was Phillis Wheatley, a West African child stolen into slavery, sold in Boston at the age of seven. She was named Philis, because that was the name of the ship that took her away, and Wheatley, after the merchant who brought her.

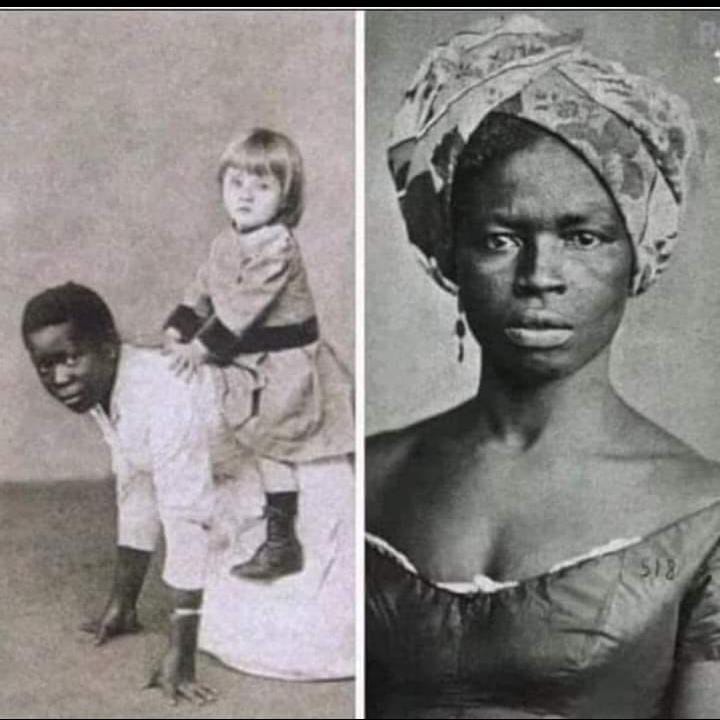

She was born in Senegal, according to historical reference, while other scholars argue she was born in Gambia. In Boston, slave traders put her up for sale:

“She is seven years old! She’ll make a good mare!” She was groped, naked, by many hands. In a world that denied her parenthood, she became something extraordinary: the first African American woman to publish a book of poetry.

Yet her legacy remains a footnote in many textbooks, her story forgotten in the folds of history she helped shape.

A PEN IN CHAINS

Image credit: Quora

Wheatley’s enslavers, the Wheatley family of Boston, Massachusetts, taught her to read and write, an unusual act in 18th-century America. By the age of twelve, she was reading Greek and Latin.

At thirteen, she was already writing poetry in a language that was not her own. No one believed she was the author of the poems she had written. She was writing poetry that stunned white audiences with its sophistication, but her talent alone wasn’t enough.

When she sought to publish her poems, Boston printers refused to believe an African girl could produce such refined work. A panel of 18 prominent white men, including governors and ministers, interrogated her to determine if she was truly the author. They needed proof. Not for her brilliance, but for her humanity.

She had to recite texts from Virgil and Milton and some passages from the bible, and she also had to swear that the poems she had written were not plagiarized. Sitting on a chair, she endured long examination until the tribunal accepted her: she was a woman, she was black, she was a slave, but she was a poet.

That she passed their scrutiny wasn’t a triumph; it was a tragedy of how deeply racism governed belief. Of how racism dictated how we related to each other. It was the gap between success, blacks, and whites.

A POET FOR THE EMPIRE, NOT HERSELF.

Her 1773 collections, poems on various subjects, Religious and Moral, were published in London. After being subjected to scrutiny and being doubted due to her origin and the color of her skin, she was finally allowed to make a publication.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

In it, Wheatley praises figures like George Washington and reflects on Christianity, morality, and death. But while her verses won her fame in the elite white circles, she was also criticized by her abolitionists for not directly condemning slavery in her work.

a woman who had lived all her life condemning the act of slavery. What they missed was this: her entire existence was protest. To be an enslaved African girl and publish in the 18th century was an act of rebellion, whether her words were wrapped in piety or poetry.

Her case was a situation of action speaks louder than words. She had rebelled against it by writing, learning, and being able to read. A quality that only the white elites possessed.

ERASED AFTER USE

.jpeg)

image credit: pinterest

Philis Wheatley was once invited to meet George Washington after she wrote to him in 1775. In her letter, she had expressed herself, showing her stance in British rule in North America, showing support for the rebellion against British rule that was ongoing in North America. She noted herself to be a liberator.

Voltaire praised her in France. But fame did not protect her. After gaining manumission(freedom), she married John Peters, a free black man, in 1778. She struggled financially, buried her 3 children in poverty, and died at the age of 31—largely forgotten by the world that once applauded her.

She had been celebrated as a symbol, but never supported as a woman. This has been the fate of many women across the nation. many notable women who have been required to prove themselves before they are recognised. Being black as a whole was already a problem.

WHY HER STORY STILL MATTERS

Image credit: Pinterest

In today’s world, where black women still have to prove they are “qualified” to sit at the tables they built, Philis Wheatley’s life is a mirror. She challenges our memory: who do we honor and who do we forget?

Her poetry defied the logic of her time. She published her first poem in 1767 and also went further to publish “An Elegiac Poem, On The Death Of The Celebrated Divine George Whitified” in 1770, which brought her great recognition. Another publication in 1773, under the financial aid of “The English Countess Of Huntingdon”, Wheatley travelled to London with her son to publish her first collection of poems; poems on various subjects, religious, and moral—the first book written by an enslaved black woman in America.

It included a forward, signed by John Hancock and other Boston notables, as well as a portrait of Wheatley, just to prove that the work was indeed written by her.

She was both a tool of empire and a silent disruptor of it. She was a black girl forced to humanize herself in verse. She reminds us that representation without liberation is not a victory, but a spectacle. A glory that should be sung for centuries to come; In classrooms, meetings, debates, and historical remembrance,

IN CONCLUSION

Philis Wheatley didn’t just write poems—she wrote herself into a world that wanted her invisible. She turned ink into resistance, verse into legacy.

Her life, though brief, was loud in a time that wanted her quiet. May we remember her not just as the “first”, but as one of many who resisted with intellect, with grace, and with fire in her pen.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...