You may also like...

Do You Know That A Flight of Stairs Could Be a Mini Workout for Your Brain and Body?

Climbing the stairs isn’t just about fitness, it boosts heart health, strengthens muscles, and sharpens brain function. ...

Lagbaja Didn't Need a Face to Become a Voice

From Abacha-era Nigeria to today’s Afrobeats boom, Lagbaja built a cultural legacy without ever revealing his face—provi...

Crisis Brews: Thomas Frank Fights for Spurs Job Amidst Relegation Threat

Tottenham Hotspur head coach Thomas Frank is under severe pressure after a 2-1 defeat to Newcastle United, with fans cal...

Catastrophic Failure: 2026's Major Horror Release Implodes by Week 3

The film adaptation 'Return to Silent Hill' has faced severe criticism and a dismal performance at the U.S. box office s...

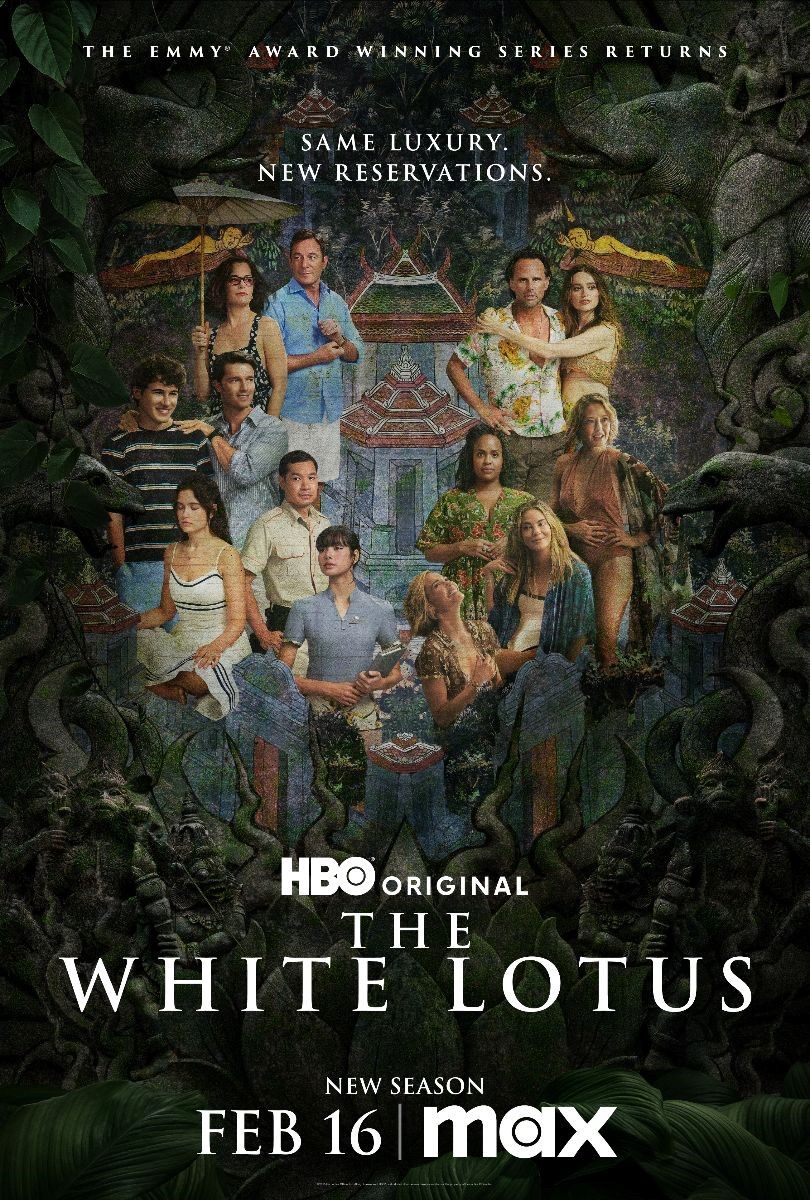

White Lotus Season 4 Lands A-List Talent, Adding 'Severance' Star

The White Lotus Season 4 is set to welcome actor and comedian Sandra Bernhard to its cast, joining other notable names f...

Music History in the Making: ARIA Unveils Landmark Standalone Hall of Fame Event

The ARIA Awards will celebrate its 40th anniversary in 2026 with a special stand-alone Hall of Fame induction ceremony o...

Adam Sandler Honored with Prestigious ASCAP Founders Award for Songwriting Genius

Adam Sandler, renowned for his comedy, is set to receive the ASCAP Founders Award for his groundbreaking contributions t...

Travel Alert: Table Mountain National Park Implements New Visitor Entry Rules

Table Mountain National Park is implementing new mandatory indemnity forms and an ID scanning system from February 10, 2...