Gen Z and millennial courage is the legacy of good education

[Collins Oduor/ Standard]

The youth are shaking the foundations of the status quo and demanding to be heard. We have witnessed with awe, and, I daresay, with a mixture of shock and trepidation, the remarkable political awakening of the youth. I think the Gen Z and millennial generations have risen, not merely to make noise or disturb the peace, but to demand accountability, justice, and a future they can believe in.

Their voices have reverberated across the land, shaking the foundations of impunity and arrogance in the corridors of power. The fundamental question that we are all asking is just what happened? Many have pondered the roots of this sense of agency and courage. Social media has, of course, played a vital role, offering a platform for connection and mobilisation. But to attribute this awakening solely to digital tools is to miss a deeper, quieter force that has been at work for years: the transformative power of literature.

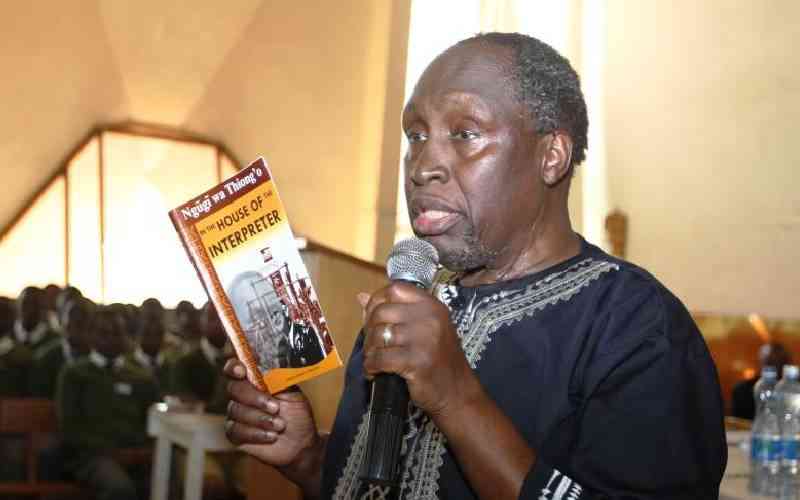

What is happening should convince the doubting Thomases about the powerful force of literature. Literature is just not for entertainment; it is a force for change. It awakens conscience, provokes thought, and inspires action. Through stories, plays, and poetry, it challenges injustice, nurtures empathy, and empowers us to imagine and work toward better futures. It shapes values, questions systems, and gives voice to the voiceless. It is a silent yet enduring engine of transformation in society.

Yes. I am saying literature is responsible for the reawakening. Those who imagine that books have little to do with the current consciousness of our youth have not been paying attention. These Gen Zs occupying public squares and interrogating authority were nourished intellectually and morally by the literature and fasihi texts they encountered in school. These texts, woven into the fabric of our secondary education curriculum, have shaped their values, sharpened their minds, and stirred their consciences. On this, the education achieved its purpose.

Let us consider Fathers of Nations by Paul B. Vitta. This text speaks profoundly to this generation. In its intricate narrative, the novel unpacks the complexities of governance, corruption, and the elusive dream of African unity. The youth who read it saw in its pages a mirror of their frustrations, with leaders who promise much and deliver little, and with systems designed to enrich the few at the expense of the many.

The Parliament of Owls by my friend Adipo Sidang offers a modern allegory of Kenya’s political realities. By casting the nation’s ills through animal characters, Sidang’ exposes greed, hypocrisy, and moral decay. The youth who studied this text found both satire and inspiration, a reminder that the fight for good governance is theirs to own. This is where the sense of agency was invoked. Let us also remember Blossoms of the Savannah by Henry Ole Kulet. This powerful novel speaks boldly to issues of gender justice and cultural oppression.

Equally significant is An Enemy of the People by Henrik Ibsen. The play’s protagonist, Dr. Stockmann, embodies the struggle of truth against popular falsehood and political expediency. The youth who engaged with this work learned that speaking out against corruption and danger, even when unpopular, is a moral imperative. They saw that the greatest enemy is not always the tyrant on the throne, but the cowardice of the majority and the betrayal of principles by the privileged few.

Consider Betrayal in the City by Francis Imbuga, a play that many of these young Kenyans encountered in their high school years. Through characters like Jusper, who dares to challenge the regime, students encountered the enduring struggle between tyranny and justice. The play taught them that silence in the face of injustice is complicity.

In the fasihi domain, texts like Kigogo by Pauline Kea and Chozi la Heri by Assumpta Matei have been equally influential. They address corruption, resilience, and the quest for truth in the face of brutal systems. Tumbo Lisilo Shiba by Ken Walibora is a compelling fasihi text that resonates deeply with the themes of corruption, greed, and moral decay in society.

For many students, this text has stirred critical reflection on governance, ethics, and personal responsibility. It challenges young readers to reject selfishness and embrace integrity as a foundation for meaningful change.

These literary works have done what great literature always does: they have nurtured empathy, provoked reflection, and emboldened action. They have given our youth a vocabulary for their discontent and a moral compass for their activism. The chants we now hear in the streets, calling for transparency, equity, and dignity, echo the lessons first encountered in these books.

It is fashionable in some circles to dismiss literature and the arts as luxuries in a nation grappling with economic and social challenges. But if ever there was proof that literature matters, that stories shape societies, it is to be found in the current wave of youth activism.

As a nation, we would do well to reflect on this. The clamour of Gen Z and millennials is not the noise of disobedience. It is the music of a generation awakened by the words of our greatest thinkers and storytellers.

The task before us now is to listen and to act. For as literature has taught us, the true betrayal is not in the failure of leaders alone, but in the failure of all of us to heed the call for justice.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter