The unsung pedagogies behind Ngugi wa Thiong'o

The adage “Without the teacher, the storyteller remains unsung,” drawn from Luke 6:40, aptly frames the life and evolution of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o—Africa’s foremost literary icon. His artistic journey did not emerge in isolation; rather, it was cultivated in the rich soil of mentorship and literary institutions across East Africa and Britain.

To grasp Ngũgĩ’s rise from a village in Limuru to global literary eminence, one must retrace the educational and ideological spaces that shaped him—most notably Makerere University College in Kampala and the University of Leeds in the UK. These academic crucibles were more than formal institutions; they were intellectual nurseries where a generation of East African writers, including Ngũgĩ, found voice, vision, and validation.

Ngũgĩ enrolled at Makerere in 1959, at a time when the university stood as East Africa’s cultural and intellectual capital. Makerere birthed what Simon Gikandi later termed the “Makerere Tradition,” a literary movement rooted in realism and social engagement. The Department of English at Makerere, which nurtured luminaries like Rebecca Njau and Jonathan Kariara, gave structure and sophistication to Ngũgĩ’s early narrative impulse.

Central to this formative phase was Professor David Cook, a British literary critic and academic who joined Makerere in the early 1960s. More than a teacher, Cook was a mentor who believed in the power of African stories. His creative writing classes were radical spaces of experimentation and critique, where Ngũgĩ penned early works like The Black Hermit—the first East African play to be professionally staged.

Cook’s role extended beyond the classroom. As patron of Penpoint and The Makererean, student journals of creative writing, he provided young writers with platforms for public engagement. Through this, he encouraged Ngũgĩ to grapple with themes like colonial injustice, identity, and displacement. Born in 1938 and coming of age during the Mau Mau uprising, Ngũgĩ’s political sensibilities found narrative form in these literary spaces.

The literary awakening of the 1960s was further marked by key publications like Origin East Africa (1965), Short East African Plays (1968), and Poems from East Africa (1971), all edited by Cook. These anthologies became cornerstones of East African literature, giving lasting visibility to voices that would shape the region’s literary landscape.

Ngũgĩ’s creative growth did not end at Makerere. In 1964, he proceeded to the University of Leeds, where he studied English literature under Professor Arthur Ravenscroft, another key figure in postcolonial literary criticism. Ravenscroft, remembered today through the annual Ravenscroft Lectures at Leeds, was deeply committed to African literature. He treated his students not as mere learners, but as fellow thinkers. Alongside fellow Makererean and Ugandan writer Peter Nazareth, Ngũgĩ developed foundational drafts of later works at Leeds.

At Leeds, Ngũgĩ encountered radical postcolonial discourse and Marxist thought. The ideological friction of post-war Britain, combined with his exposure to thinkers like Frantz Fanon and George Lamming, gave Ngũgĩ’s writing a new urgency. His novels began to reflect the ideological underpinnings of resistance, class struggle, and cultural reclamation, evident in later works such as A Grain of Wheat, Petals of Blood, and Devil on the Cross.

His symbolic decision in the 1970s to drop his English name, “James Ngugi,” and embrace “Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o,” was more than a personal statement. It was a rejection of colonial naming systems and an affirmation of African identity. Language became both a tool of resistance and a site of struggle. His pivot toward writing in Gikuyu was informed by the very mentors who had challenged him to interrogate the politics of language.

The myth that great writers are born without formal education is here disproven. Ngũgĩ’s life story affirms that literary talent, when coupled with structured mentorship and academic engagement, can blossom into revolutionary art. As a literary critic and educator myself, I recognize this truth in my own work of mentoring budding talents—many of whom have gone on to careers in publishing, media, and theatre.

Indeed, many celebrated African writers—Wole Soyinka (Ibadan), Ebrahim Hussein (Dar es Salaam), Micere Mugo (Nairobi and Makerere), and Ama Ata Aidoo (Ghana)—benefited from similar academic environments. These institutions—often collectively referred to as the “Ibadan School of Writing” and the “Makerere Tradition”—were not simply sites of learning; they were sites of literary production, dialogue, and cultural affirmation.

Ngũgĩ’s own success must be seen in this context. Scholars like Carol Sicherman, in her biographical study Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: The Making of a Rebel (1990), and the late Professor Chris Wanjala, in his foundational lecture The Growth of an East African Literary Tradition (2003), have mapped out these intellectual genealogies. Wanjala, a former student of Ngũgĩ, emphasized that literary traditions are not born spontaneously—they are cultivated through mentorship, critical engagement, and institutional support.

Ngũgĩ’s own trajectory—from Limuru’s ridges to the halls of Leeds and beyond—is a powerful testament to the powerful potential of education and mentorship. Without the editorial hand of Cook or the critical challenge of Ravenscroft, it is doubtful that The River Between or Weep Not, Child would have emerged in the form they did.

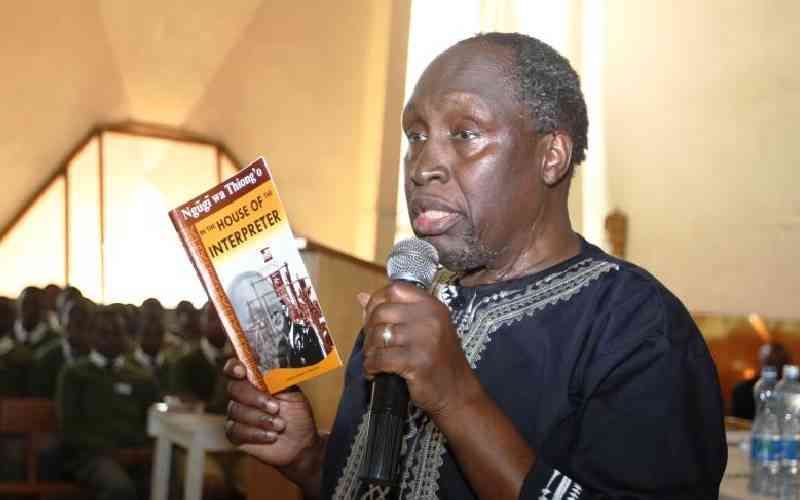

Ngũgĩ did not end the chain of mentorship. He became a torchbearer himself, mentoring writers, students, and scholars across continents. Through lectures, essays, and public engagements—including email exchanges and social media posts—he extended the same generosity that once shaped him. His story illustrates how mentorship doesn’t just create writers—it creates writer-builders.

It saddens me that he won’t be present at the forthcoming launch of a commemorative book in honour of his former student and my colleague, the late Wasambo Were. Ngũgĩ had been keen to contribute to this festschrift, having acknowledged Wasambo as his first class representative at the University of Nairobi. Yet his absence only affirms his legacy—his life continues to inspire those of us committed to literary education and cultural stewardship.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

As we reflect on his journey, we are reminded that the next Ngũgĩ may already be sitting in a classroom in Nairobi, Eldoret, Dodoma, or Gulu. The question is: will they find their David Cook, their Arthur Ravenscroft—or even their Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o?

A luta continua! Rest in peace, teacher of teachers. Go forth well, Mwalimu.

Dr Justus Makokha teaches Literature and Theatre Arts at Kenyatta University.