Faith and Flag: Religion and the Foundations of Patriotism in African Societies

There’s a lot more to this whole story of faith, flag, and African identity than just a bunch of missionaries showing up and thinking they’re the main characters.

First off, you can’t overstate how much religion was already baked into the bones of African societies before anyone ever heard the word “missionary.” Seriously—every family, every clan, every king had their own spiritual playbook. Ancestor worship, divination, rituals—these weren’t just side gigs, they were the main event. Religion wasn’t some Sunday habit; it was how you made sense of the world, how you got along with your neighbors, even how you picked your leaders. It was law, order, and the unwritten constitution all rolled into one.

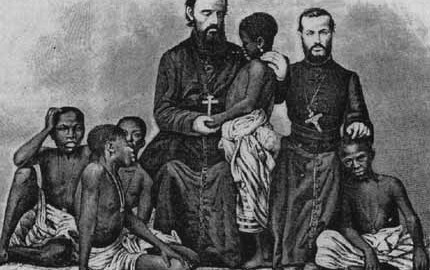

Now, enter the missionaries. Imagine a bunch of Europeans rolling into town, convinced they’ve got the ultimate upgrade for your soul and society. It wasn’t just about preaching Jesus; they were on a full-blown civilizing mission. They built schools, sure, but it wasn’t just reading, writing, and arithmetic. It was about turning Africans into, well, little Europeans—changing clothes, changing customs, changing everything.

But, here’s where it gets wild—while a lot of that “civilizing” stuff was straight-up cultural arrogance, the education that came with it was a double-edged sword. Mission schools didn’t just churn out obedient subjects; they created thinkers, writers, and rebels. Africans started to read the Bible for themselves, and, honestly, they picked up on all the parts about justice, freedom, brotherhood—stuff that the missionaries maybe didn’t want them to focus on too much. Whoops.

Think about it: you’re told “all men are equal before God,” but then you look around and see white missionaries and colonial officers running the show, while locals are treated like second-class citizens in their own land. So yes your guess is as good as mine, the people didn't stay quiet —they started asking the hard questions. Churches quietly became places where these ideas could take root and grow. Not exactly what the colonial powers had in mind.

So, by the time the twentieth century rolled around, you had a whole new generation of Africans who’d gone through the mission school system. They could read, write, argue, and organize. Churches and mission outposts turned into unofficial town halls, places where people could debate what it meant to be African—and what it would take to run things for themselves instead of being bossed around by outsiders.

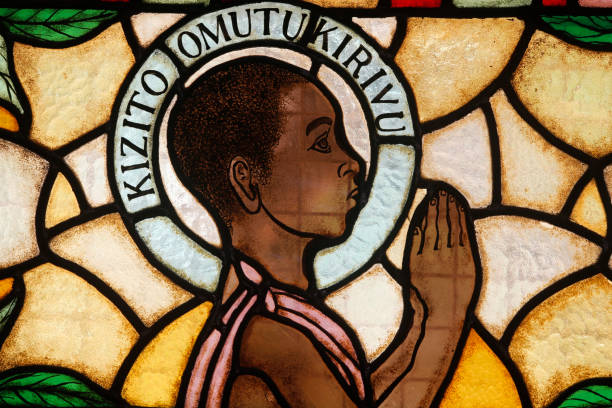

Let’s talk about some of the heavy hitters. Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther was a legend—more than being the first African Anglican bishop,he also insisted that African culture and Christianity could coexist. And was responsible for one of the earliest translations of the bible to Yoruba. That’s not just religious work; that’s about reclaiming language, identity, and pride. James Johnson in Sierra Leone was in the same league—preaching Christianity, but on African terms, not as a carbon copy of the British model. These men weren’t just spiritual leaders; they were early nationalists in their own right.

You see this pattern everywhere. Take Ghana, for example—those old-school Presbyterian and Methodist churches basically set the stage for brainy, bold leaders like Kwame Nkrumah. Flip over to Kenya, and you’ve got Jomo Kenyatta. Sure, he got less religious as he got older, but that early mission school vibe gave him a whole dictionary of moral lingo. South Africa? That’s a wild one. The church there wasn’t just about singing hymns and Sunday sermons; it became this defiant stronghold against apartheid. People like Albert Luthuli and Desmond Tututhose turned faith into a rallying cry, while somehow managing to talk about forgiveness and justice in the same breath. Which is not an easy feat.

Honestly, religion wasn’t just about soothing people’s pain. It gave folks a way to dream up freedom, like real, big-picture freedom—not just swapping one flag for another. Religion added a deep meaning to African nationalism. It wasn’t entirely political; it was a virtuous cause.

Fast-forward to, flags going up everywhere, and amongst the chaos and hope all mixed together in independence—mid-1900s. Suddenly, people had to figure out how to whip up a sense of “us” out of, like, fifty different languages and a wild patchwork of cultures. Guess what they reached for? Religion. What used to be a colonial thing started turning into something way more—like a kind of moral GPS and a badge of unity. Some leaders meant every word, some were just playing the crowd, but either way, they leaned hard on religious talk to call for honesty, sacrifice, a fresh start.

Take Nigeria. Islam and Christianity both got totally woven into daily life. Churches and mosques became way more than places to pray—think town halls where people hashed out justice, corruption, all the big stuff. Ghana? Their Christian Council and Catholic Bishops, those folks didn’t just hang back. They called the government out when it started to slide.

And of course, just like everything else religion can be used as a tool, to bring people together, and as well blow things apart if someone decides to play dirty. Some politicians can use religious tensions to win votes or to push others to the sidelines. That’s led to some really dark chapters—northern Nigeria, Sudan’s border zones, you name it. Still, even in the middle of all that mess, religious leaders are often the only folks people actually trust to help make peace.

Now? Religion as always continues to shape public life in ways that make total sense for the most part—and other times don’t. We have religious schools, hospitals and even soup kitchens,. standing up for the regular folks when the government decides to go silent. And when things fall apart, who do people look to? Not the politicians, that’s for sure. It’s the religious leaders—because, for whatever reason, people still believe they’re speaking from the heart, not just playing some cynical game.

There’s no shortage of wild examples, honestly. Just look at Desmond Tutu—dude basically became the face of forgiveness in South Africa, running the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and showing the world that faith can actually patch up a country that’s been torn to shreds. Hop over to Kenya and you’ll find Christian and Muslim leaders teaming up, telling everyone to chill out when elections get heated (which is, let’s be real, every time). And in Nigeria? Forget the government half the time; churches and mosques are the ones handing out food, giving people a roof, and just generally playing therapist for communities that got the short end of the stick.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

However, if zoomed out the bigger picture could be seen, religion’s been tangled up in Africa’s story from the jump. Missionaries rolled in with their own agenda, but somewhere along the way, that whole project flipped—faith turned into a weapon for freedom and something people could build an identity around. Those mission schools? Sure, they taught scripture, but they also opened up the world for a lot of folks.

After independence, religion didn’t just fade out. It stuck around, poking at everybody’s conscience and kicking off movements. Religion has since then become the soul behind patriotism.

So Faith has a place in every country that is more than just waving a flag—it has its place in a country that believes in its people and is rooting for a better tomorrow.

You may also like...

Be Honest: Are You Actually Funny or Just Loud? Find Your Humour Type

Are you actually funny or just loud? Discover your humour type—from sarcastic to accidental comedian—and learn how your ...

Ndidi's Besiktas Revelation: Why He Chose Turkey Over Man Utd Dreams

Super Eagles midfielder Wilfred Ndidi explained his decision to join Besiktas, citing the club's appealing project, stro...

Tom Hardy Returns! Venom Roars Back to the Big Screen in New Movie!

Two years after its last cinematic outing, Venom is set to return in an animated feature film from Sony Pictures Animati...

Marvel Shakes Up Spider-Verse with Nicolas Cage's Groundbreaking New Series!

Nicolas Cage is set to star as Ben Reilly in the upcoming live-action 'Spider-Noir' series on Prime Video, moving beyond...

Bad Bunny's 'DtMF' Dominates Hot 100 with Chart-Topping Power!

A recent 'Ask Billboard' mailbag delves into Hot 100 chart specifics, featuring Bad Bunny's "DtMF" and Ella Langley's "C...

Shakira Stuns Mexico City with Massive Free Concert Announcement!

Shakira is set to conclude her historic Mexican tour trek with a free concert at Mexico City's iconic Zócalo on March 1,...

Glen Powell Reveals His Unexpected Favorite Christopher Nolan Film

A24's dark comedy "How to Make a Killing" is hitting theaters, starring Glen Powell, Topher Grace, and Jessica Henwick. ...

Wizkid & Pharrell Set New Male Style Standard in Leather and Satin Showdown

Wizkid and Pharrell Williams have sparked widespread speculation with a new, cryptic Instagram post. While the possibili...