What’s the future of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, or DFC? A memo that circulated last week offers one potential vision, and an executive order signed the same day by U.S. President Donald Trump presents another.

The executive order signed on Thursday focuses on , invoking emergency powers to lessen U.S. reliance on foreign sources. It calls on DFC to help fund some of those projects. If that seems surprising, it might be because DFC’s mandate is to invest internationally to further development and foreign policy objectives.

Sign up to this weekly newsletter to get the insider brief on business, finance, and the SDGs in your inbox every Tuesday.

Another vision for DFC can be found in the memo, one of several proposals floating around for how to structure the future of U.S. aid. It suggests that the Millennium Challenge Corporation and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency . (I’ll note that this proposal’s authors are unknown, though Politico reported it was written by Trump’s aides. Several sources tell me they believe it’s likely not the administration’s position.)

There have also been rumors that for the U.S. — or become such a fund, or become home to other funds with specific objectives. The agency is also up for reauthorization this year — providing an opportunity to reshape it. But a recent congressional hearing featured mostly previously discussed ideas for how to tweak the agency.

Memo lays out plan to replace USAID with new humanitarian agency

Congressional hearing kicks off DFC reauthorization efforts

Under Trump’s executive order, DFC will be through the Defense Production Act. DFC will provide loans “that create, maintain, protect, expand, or restore domestic mineral production,” and it will also be able to provide loan guarantees and political risk insurance.

The order also gives 30 days for DFC’s CEO and the defense secretary to develop and propose a plan to . (While Benjamin Black has been nominated to be DFC CEO, he has not yet been confirmed.) DFC will manage those investments with U.S. Department of Defense funding and consultation with other parts of the government.

“DFC will now be pivoting much of its capacity to domestic minerals investments,” write Gracelin Baskaran and Meredith Schwartz in an analysis for the Center for Strategic and International Studies that posits DFC could change significantly, and the executive order .

“All of this is very peculiar” and is “so antithetical to the mission” of DFC, Clemence Landers, vice president and senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development, tells me. She has a number of questions: about the financial additionality of the investments, about staffing up a domestic focused arm of an already stretched agency, and why DFC and not other agencies. “It also kind of makes me wonder, is this one step in the direction of sort of making DFC into a sovereign wealth fund?”

In early February, Trump signed an executive order directing the treasury and commerce secretaries to come up with a plan to establish a sovereign wealth fund within 90 days. Reports also emerged that some in the administration were discussing turning DFC into a sovereign wealth fund. , Landers wrote at the time.

But it’s not the first time that DFC has been directed by the Trump administration to make domestic investments. And as it embarks on that journey again, it’s worth taking a look at how things went the first time around: .

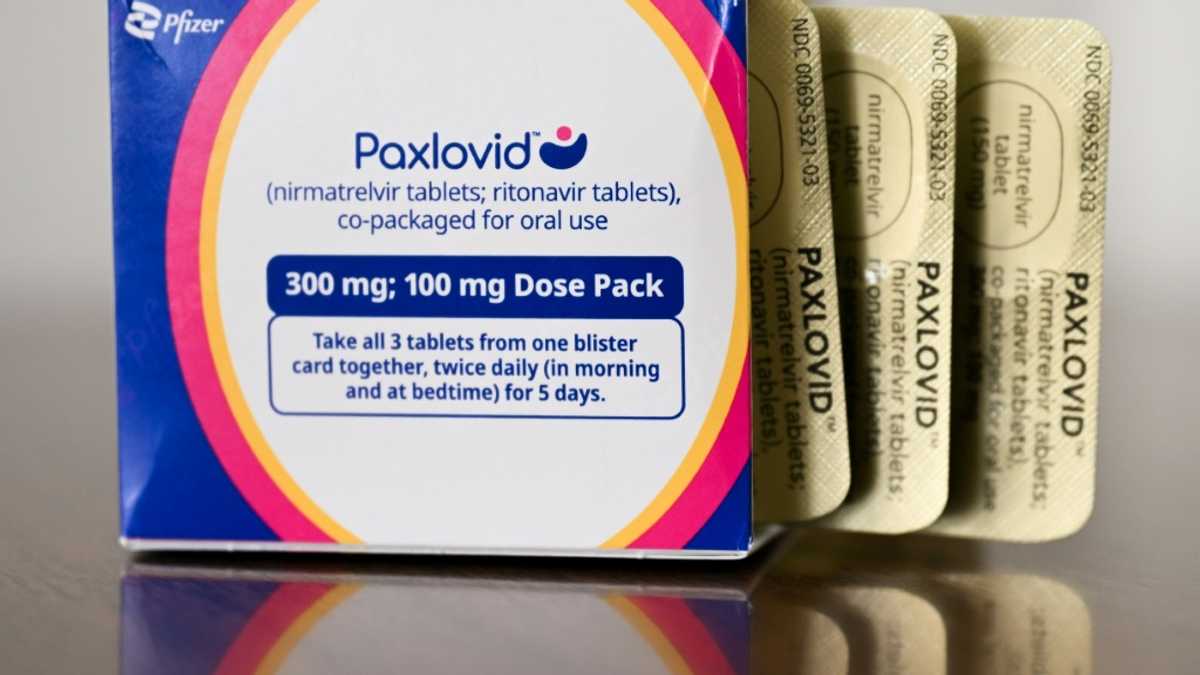

In May 2020, the first Trump administration gave DFC authority to invest in the U.S. to help build COVID-19 supply chains. Not long afterward, DFC signed a letter of interest to provide the Eastman Kodak Company with a $765 million loan to support the launch of the camera and film company’s new arm to produce pharmaceutical components. That letter resulted in investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the U.S. House of Representatives. Two people were eventually , which never resulted in a loan.

Other loans were announced — including $590 million to ApiJect Systems to develop a new factory in North Carolina that would produce syringes — but it’s unclear whether they ever materialized. In 2023, DFC announced that it had executed a $410 million loan to National Resilience, Inc. to support manufacturing and delivery of vaccines and critical minerals around the country as part of the Defense Production Act, or DPA, loan program. It also noted at the time that the commitment to provide Resilience with a loan in March 2022 “marked the end of DFC’s role in sourcing projects under the program,” which had a two-year authorization period.

The Government Accountability Office also investigated the program and released a report in November 2021 finding that the process was slow and complex and of carrying out the DPA Loan Program along with its primary mission.”

It offered two recommendations — that DFC develop a plan to evaluate the program’s effectiveness, and that it complete its systems for accounting for program costs. While DFC has implemented the accounting recommendation, it has not developed a plan to monitor the DPA program’s effectiveness. GAO has recently updated its report, saying “As of March 2025, DFC reported no additional actions to implement the recommendation,” adding that it will continue to monitor DFC’s actions.

GAO report assesses US DFC domestic loan program

The aforementioned memo offering a vision for how the Trump administration could restructure aid outlined a plan to bring MCC and USTDA into DFC with a “ via trade, investment, infrastructure (physical and digital), projecting America’s energy and technology dominance.”

It said that MCC and USTDA would retain their authorities and criteria for investment as separate divisions but work to pave the way for DFC-supported deals. It also set up the new entity as .

The potential blueprint also suggested the creation of a new development insurance facility that would prioritize returns on investment and create opportunities for U.S. businesses and consumers. Success would be measured by capital mobilized, financial returns generated, jobs created, and development outcomes.

New money would come to the agency from accounts that previously were funneled through USAID and the U.S. State Department. The proposal also suggested that the Office of Management and Budget would , which has constrained the agency’s ability to make equity investments since its creation.

The proposal to bring MCC and USTDA into one agency under DFC . In fact, it was floated in the first Trump administration when DFC was created, a former Trump administration official tells me. While it didn’t happen then, DFC’s board was structured in a way that mirrored MCC’s in order to allow them to work closely or someday merge, the former official says.

“It would get a little messy, but isn’t insurmountable with things being built from the ground up,” the former official tells me.

It’s unclear if this proposal will gain traction but to change statutes and funding allocations. The DFC reauthorization could provide an avenue to do so, though the recent hearing on the matter did not broach these broader changes.

How is this ‘reimagined’ proposal for USAID hitting the sector?

Unpacking proposals to overhaul US foreign aid

The World Bank , its president, Ajay Banga, says. [Bloomberg]

Former USAID chief economist on . [Devex Pro]

Viewpoint: Rethinking private capital for development and . [Impact Investor]

: A continued investment opportunity. [UBS]

Slashed aid budgets . [Professional Wealth Management]

Has U.S. aid been [Devex]