'Demonstration Of Craze' And The Burden Of Activism, By Abdul Mahmud | Sahara Reporters

On Thursday, 29th May 2025, a book presentation was held in Abuja to mark the 26th anniversary of Nigeria’s return to civil rule. The book, 'Demonstration of Craze: Struggles and Transition to Democracy' by Abdul Oroh, is a timely reflection on a journey that has staggered rather than soared. The hall was filled with familiar names and faces. From Olisa Agbakoba, Ayo Obe, Tunji Abayomi, Adebayo Bodunrin, Omoyele Sowore, Chris Uyot, Chido Onumah, Uche Onyeagocha to Adams Oshiomhole. All veterans of the struggle against military dictatorship and younger activists disillusioned by what has become of the “democracy” they were promised. It was more than a book presentation. It was a convocation of disappointments. A reunion of warriors, many of whom are in their winter years, turned watchers. It was also an opportunity, albeit missed in some regards, to interrogate the long and painful arc of our country's post-military experience.

Omoyele Sowore, a comrade-in-struggle who emerged from the students movement, threw the first grenade. He accused the political class of squandering the promise of civil rule. He went further. He blamed the activist movement for walking away from the political transition programme of General Abdulsalami Abubakar in 1999. In his view, that singular act created a vacuum that allowed what he described as “bandits” to hijack power.

That is a weighty charge that many members of the activist movement have consistently made at one time or the other.

Sowore merely re-echoed it.

But he didn’t speak to the cool air filtering from the airconditioners in the hall. He spoke to comrades, witness-participants of that era of the struggles against military dictatorship. Olisa Agbakoba, SAN, one of the leading titans of the movement, responded. He accused Sowore and other activists of having championed the very purist ideals that kept the activist movement from engaging the transition process. In other words, they helped orchestrate the political marginalisation of the activist movement.

That’s a serious rebuttal.

Yet, Agbakoba’s rebuttal, pointed though, lacked the nuance that the moment demanded. In countering Sowore’s position, he overlooked the historical schisms that fractured the pro-democracy movement in the turbulent aftermath of the June 12 annulment. By doing so, he inadvertently cast the entire movement under a single, damning brushstroke, which tarred its legacy with the charge of collective miscalculation.

The reality, however, was far more complex.

At the heart of the movement’s crisis was a deep ideological divide of two irreconcilable tendencies which battled for the soul of the resistance. One camp, pragmatic in outlook, advocated for direct participation in the political transition programme following the betrayal of politicians mainly from the NADECO who jumped readily on Abacha's train. Don't forget that Kingibe who was Abiola's vice presidential candidate joined the train. These activists sought to transform the Campaign for Democracy (CD) into a political party that could contest for power. They believed that true transformation required not just agitation from the margins, but active engagement within the political. This group was largely composed of activists associated with the Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO), the Socialist Congress of Nigeria (SCON), and other progressive formations like Women-in-Nigeria (WIN) that believed in leveraging the available political space, however flawed. The opposing camp, however, viewed such participation as sacrilege. For them, any involvement in General Abdulsalami's short political transition amounted to a betrayal of the June 12 mandate; a sacred covenant that must not be compromised. They saw the elections of June 12, 1993, won by Chief M.K.O. Abiola; and annulled by General Babangida as the people’s mandate. And any political process that failed to restore that mandate was illegitimate. This group, anchored mainly activists from the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights (CDHR), as well as some activist-lawyers from the chambers of Gani Fawehinmi and Femi Falana, clung to their defiance.

The ideological rifts resulted in the historic and bitter factionalisation of the Campaign for Democracy at its national convention in Ibadan late 1994. The pro-participation activists would go on to establish a political party of their own - the Democratic Alternative - a vehicle through which they hoped to enter the emerging democratic space. They applied for registration in 1998. But the party was never granted recognition by the National Electoral Commission (NEC), effectively excluding it from the process.

Gani Fawehinmi, unyielding as ever, would later found the National Conscience Party (NCP). He refused to participate in the transition. Femi Falana echoed that posture. Together, Gani and Falana denounced the pro-transition activists as ideological apostates, accusing them of abandoning the core principles of the struggle. They saw the quest to participate in the transition programme as an unacceptable accommodation with authoritarianism; a betrayal of June 12.

There was yet a third tendency within the broader pro-democracy coalition: the emergent bloc that found kinship with the Democratic Alternative which was rooted in Port Harcourt. This group, composed of environmental rights campaigners, militants, and fragments of the motley M23 formation, projected a different rhythm in the dance of resistance. Their struggle was shaped not just by ideological abstraction, but by the visceral realities of environmental devastation of the Niger Delta. Led by the late Oronto Douglas and Jaye Gaskia, this Port Harcourt tendency seemed more open to engaging with the military’s transition programme. Chima Ubani, a respected voice in the Lagos cell of the Democratic Alternative, was dispatched to broker alignment or at least understanding. But what followed was not the harmonisation of strategy; but an ambush. The encounter in Port Harcourt degenerated into chaos. Hostilities flared. The ideological fault lines that ran through the broader movement were laid bare in that moment, not merely as theoretical divergences, but as lived antagonisms. Emotions boiled over. And in a deeply regrettable episode, some Port Harcourt-based activists unleashed physical violence on their supposed comrades from the Democratic Alternative. It was a jarring reminder that even among those who claimed the language of justice, the tools of intolerance could still be wielded.

The incident was more than a disruption of a meeting. It symbolised the deeper crisis of cohesion that haunted the Nigerian resistance movement in the 1990s. Unity proved elusive, not because the struggle lacked passion or courage, but because it lacked consensus on strategy, on vision, on the contours of the future being fought for. In that combustible mix of principled conviction, puritanism, wounded egos, and ethno-regional grievances, the seeds of mutual alienation were sown. And the cracks that emerged then widened over the years, making the task of building a post-military democratic project all the more fragile. This internal rupture in the pro-democracy movement was more than a strategic disagreement. It was a philosophical divergence about the nature of power, legitimacy, and resistance. One side believed in incremental engagement; the other in uncompromising fidelity to a stolen mandate.

Ironically, and perhaps inevitably, those who had once stood resolutely against participation in the General Abdulsalami's transition programme eventually found themselves drawn into the very structures they once denounced. Time, as ever, had a way of unmasking the limits of puritanism in the face of political reality. When the dust settled and the so-called transition had been completed, not with activists at the helm; but with opportunists and career politicians occupying the corridors of power, many from the old vanguard were forced to reckon with the consequences of absence. By then, the die had been cast. The gates of governance had been shut; and bandits, metaphorical and literal, had seized the nation-state. Femi Falana would later test his popularity in the ballot box in Ekiti State. He lost woefully. Gani Fawehinmi ran for the presidency on the platform of the National Conscience Party. But he, too, was rebuffed. The citizens, weary and wary, chose otherwise. And Oronto Douglas would, in the fullness of time, serve as a Special Assistant and later commissioner to Governor Diepreye Alamieyeseigha of Bayelsa State, a man who would later become the poster face for the corruption of the Fourth Republic.

All of this was so much a betrayal as it was a belated and tragic accommodation with the political terrain as it existed. What began as refusal ended in embrace. The activists who had once vowed to never dine at the table of power found themselves, years later, negotiating for a seat, even if at the fringes. History is not without its ironies. The very system they had resisted absorbed some of them, slowly and subtly. And in that absorption, the lines between resistance and compromise began to blur.

Agbakoba, therefore, missed an opportunity to acknowledge the dialectic of that moment, the high stakes, the conflicting choices, and the conflicting moral obligations. By glossing over the small details of this history, he inadvertently erased the legitimate anxieties that informed the positions taken by both sides. It is important to state that neither side emerged vindicated. The movement’s fragmentation weakened its leverage. Its inability to present a unified front allowed military actors to manipulate the transition process with minimal resistance. Worse still, the ideological fragmentation sowed seeds of mutual suspicion that lingered long into the Fourth Republic. And yet, from the ashes of that division arose hard questions that continue to haunt civil rule in our country today.

So, what then is the role of activists in transition? Should they remain moral voices outside it, or become political actors within it? At what point does engagement become co-option? And when does purity become paralysis? The story of our country's faltering democracy cannot be told without confronting these questions and without acknowledging the historical fault lines within the very movement that fought to birth it. That is the complexity which any honest reckoning must engage. But the Sowore-Agbakoba exchange only scratched the surface. Nobody fully addressed the deeper question because the microphone wasn't passed round: why has civil rule, twenty-six years after its return, continued to flounder in our country?

The answers lie somewhere between complicity, complacency, and contradiction.

Here is my take: what our country returned to in 1999 was civil rule and not democracy. The military handed over power to civilians, but the substance of governance remained deeply authoritarian. Yet, the ceremony of elections gave the illusion of choice. This civil rule, wrapped in democratic robes, quickly became a parody of democracy. Those who fought for democracy were not necessarily the ones who came to power. Many chose to stay out. Those who joined got co-opted. A few opted out, disgusted by the compromises required.

The result? Those who assumed leadership were products of the very forces the activists fought against: moneybags, ex-military officers, and political jobbers. Worse still, some of the activists who entered politics quickly became indistinguishable from the political class. Power diluted their ideals. Privilege numbed their sense of outrage. A few became ministers, commissioners, lawmakers, and governors. But instead of reforming the system, they conformed to it. These activists know themselves.

That’s part of the tragedy.

The Sowore-Agbakoba exchange also brings another contradiction into sharp focus. The older generation of activists is torn between regret and justification. The younger generation is angry. And our fellow citizens are disillusioned. Activism has always played a central role in shaping our country's political landscape. From the anti-colonial struggles to the battles against military dictatorship, activist movement has often been the conscience of the nation. But post-1999, that role has become acute. The consciences of the nation have become hatchet men, the undertakers of the Republic. This is part of the reasons why civil rule remains hollow today.

It’s not enough to blame the political class. The activist movement must also interrogate its role. The decision to boycott the 1999 transition process, as Sowore pointed out, left the field open to opportunists. But Agbakoba’s response partly reminds us that this was not a unanimous decision. It was a contested moment. One side capitulated to the blackmail and ethnic whistling of the other side. But the decision to boycott masked a bigger problem that many within the activist movement refused to acknowledge: the activist movement lacked an agreeable political strategy. It had moral capital, but lacked institutional framework for power. It knew how to resist, but didn't know how to organise itself for power. Professor Odion Akhaine made similar points in our private conversation on Democracy Day in 2024.

Power abhors a vacuum. And in 1999, the vacuum was quickly filled. This absence of political infrastructure among activists is still a problem today. Many activists remain outside the formal political process, leaving it to be dominated by career politicians. Yet, activism without political influence becomes mere protest. If democracy is to be more than a "demonstration of craze", pro-democracy actors must rethink their strategy. They must build movements that can win power. And use it differently.

Another issue that was not explored at the book presentation was the complicity of some former activists who joined the military’s transition train. These ones, far from being democratic apostles, became undertakers of civil rule. Some became governors. Others became legislators, commissioners, or advisers. But their conduct betrayed everything they once stood for. This betrayal has deepened public cynicism as citizens now view activists-turned-politicians with suspicion. And rightly so. When those who once chanted “aluta” now chant “allocation,” trust is broken. When those who once marched for justice now scheme for contracts, the struggle is emptied of meaning. The complicity of some activists in the decay of civil rule deserves scrutiny. Many of the individuals who were once at the forefront of the struggle against military tyranny, who risked their lives and livelihoods for a freer country, eventually entered government after 1999. But instead of bringing the values of the barricades with them, they adopted the vices of the establishment. They didn’t just betray the cause, they de-legitimised it. They confirmed the fears of ordinary folks that politics is not a place for principle, but for plunder.

But not all is lost.

There remains a generation of activists, old and young, still committed to genuine change. What they need is coherence, coordination, and courage. They must develop clear political goals. They must build alliances beyond civil society. They must learn to contest elections, shape policies, and reform institutions. Street protests are important. But structural transformation requires political engagement. More importantly, they must reconnect with the people. One reason civil rule has failed is that it is disconnected from the governed. Democracy, to be meaningful, must be participatory. It must be inclusive. It must deliver dividends. So far, it hasn’t. The task now is to close that gap. That means rethinking the politics of the activist movement. It also means confronting the uncomfortable truth that our democracy is broken - and activists must earnestly begin the task of fixing it.

Book presentations like Abdul Oroh’s are important. They help us remember our struggles against inimical power. How did Milan Kundera put it again? Aha, we must pitch memory against forgetting! We must move to action. It’s not enough to gather, reminisce, and bemoan. The transition to democracy is not a date on a calendar. It is a daily struggle. The struggle that ensures that civil rule becomes truly democratic. That power is accountable. That citizens matter. For now, our civil rule remains a demonstration of craze, a circus of politicians in agbada, pretending to serve, while they loot and lie. That must change. And it won’t change on its own. It will take new thinking. New alliances. New courage. And yes, new activism; one that remembers the past but is not trapped in it. One that learns from its mistakes. One that dares to dream again.

The road ahead is hard. But if activists who once faced bullets for freedom cannot face ballots for change, then the activist movement has truly lost the plot. Democracy must not be reduced to anniversaries and ceremonies. It must be lived. And fought for. Every day. By all of us.

This is our burden.

You may also like...

The Names We Carry: Why Africa’s Many-Name Tradition Shouldn’t Be Left Behind

"In many African communities, a child's birth is marked with a cascade of names that serve as fingerprints of identity, ...

WHY CULTURAL APPROPRIATION ISN’T ALWAYS OFFENSIVE

In a world of global fusion, is every act of cultural borrowing theft—or can it be respect? This thought-provoking essay...

Africa’s Health Revolution: How a New Generation is Redefining Global Wellness from the Ground Up

Move beyond the headlines of health challenges. Discover how African youth and innovators are using technology, traditio...

Kwame Nkrumah: The Visionary Who Dreamed of a United Africa

(13).jpeg)

Discover the powerful legacy of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president and a pioneer of Pan-Africanism, whose vision for...

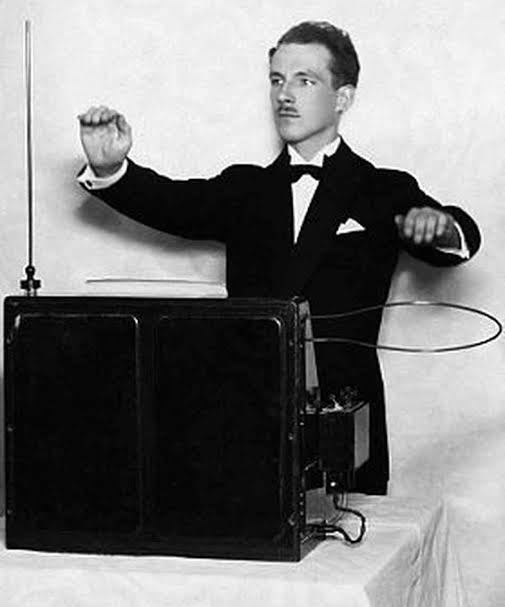

Meet the Theremin: The Weirdest Instrument You’ve Never Heard Of

From sci-fi movies to African studios? Meet the theremin—a touchless, ghostly instrument that’s making its way into Afri...

Who Told You Afro Hair Isn’t Formal?

Afro hair is still widely seen as unprofessional or “unfinished” in African society. But who decided that coils, kinks, ...

1986 Cameroonian Disaster : The Deadly Cloud that Killed Thousands Overnight

Like a thief in the night, a silent cloud rose from Lake Nyos in Cameroon, and stole nearly two thousand souls without a...

How a New Generation is Redefining Global Wellness from the Ground Up

Forget fast fashion. Discover how African designers are leading a global revolution, using traditional textiles & innov...