BMC Medical Ethics volume 26, Article number: 96 (2025) Cite this article

Advance care planning (ACP), a cornerstone of ethical end-of-life care, upholds patient autonomy. However, its practice in Confucian-influenced societies, like China, is significantly shaped by cultural norms where family preferences often precede individual choice. This study explored cultural and ethical barriers to ACP implementation among oncology nursing professionals, focusing on tensions between patient-centered care and deeply rooted social norms.

A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted on open-ended responses from oncology hospitals across 22 provinces, 4 municipal cities, and 5 autonomous regions in China. Data were collected via a cross-sectional online survey and analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s framework to identify patterns in cultural, ethical, and communicative challenges.

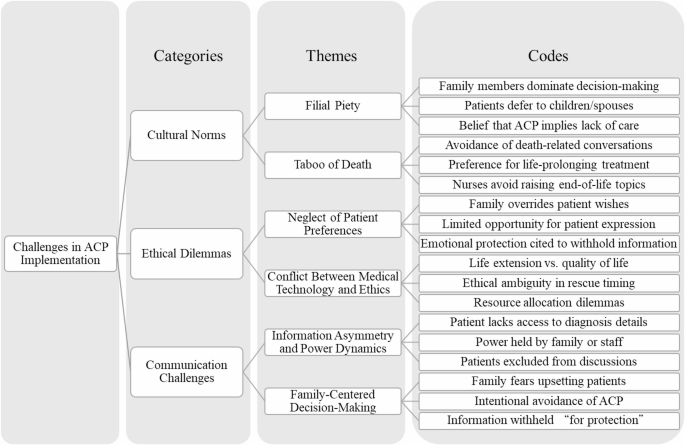

A total of 838 oncology nursing professionals participated in the study. Three main interdependent barriers emerged: (1) Cultural norms, including filial piety (15.6% of codes) and death-related taboos (11.0%), often led to family-mediated decision-making (33.1%) over patient autonomy; (2) Ethical dilemmas involved neglecting patient preferences (24.3%) and conflicts between life-prolonging treatments and quality-of-life considerations (8.1%); (3) Communication challenges arose from information asymmetry (7.9%) and power imbalances, which often silenced patient voices. These factors collectively created systemic obstacles to ACP implementation.

Context-specific ACP strategies in China should integrate Confucian ethics into nursing education, support ethics consultation, and develop culturally sensitive communication models. Future research must assess these interventions’ impact on balancing cultural values and patient autonomy, advancing equitable end-of-life care in culturally diverse healthcare systems.

Not applicable.

Advance care planning (ACP) has emerged as fundamental component of quality end-of-life care, with profound implications for patient autonomy and dignity [1,2,3]. By enabling the explicit articulation of future healthcare preference, ACP not only ensures alignment between care delivery and personal values, but also substantially mitigates the moral and emotional burden on families and nursing professionals during critical periods [4]. Beyond guiding medical decision-making, ACP plays a critical role in upholding ethical integrity and protecting patient rights within healthcare systems [5].

Despite its recognized importance, ACP implementation varies markedly across cultural contexts, reflecting diverse approaches to healthcare decision-making and distinct conceptions of patient rights. While Western healthcare systems predominantly prioritize individual autonomy and direct patient engagement in decision-making [6, 7], many Asian cultures, particularly those influenced by Confucianism, embrace a family-centered approach [8]. These cultural distinctions present substantial challenges to ACP implementation, as traditional values intersect with modern medical ethics and patient-centered care models. In this complex landscape, nurses, due to their continuous and intimate contact with patients and families at the bedside, are uniquely positioned to initiate and facilitate ACP discussions [9]. They serve as primary communicators and educators, making their role pivotal in navigating these culturally sensitive conversations.

Within Confucian-influenced societies, two cultural dimensions significantly influence ACP implementation: filial piety and death-related taboos. Filial piety, a cornerstone of Chinese family values, often overrides the patient’s personal preferences [10]. Concurrently, deeply ingrained cultural taboos surrounding death discussions create profound obstacles to initiating ACP conversations [11, 12], complicating efforts by healthcare professionals to facilitate patient-centered planning. These factors collectively contribute to ethical dilemmas in ACP, as nursing professionals must navigate tensions between respecting familial authority and safeguarding patient autonomy. Their frontline position means they are often the first to encounter these ethical conflicts [13], bearing the direct responsibility of mediating between conflicting values while delivering compassionate care.

While existing research has illuminated key aspects of ACP implementation globally, significant knowledge gaps persist, particularly regarding the ethical challenges nurses face in culturally complex healthcare environments. Most critically, there is a marked absence of research examining how nurses navigate the intersection of traditional cultural values and modern bioethical principles in ACP implementation [6, 8]. While international studies have extensively examined the ethical and practical dimensions of ACP, empirical research in Chinese healthcare contexts remains severely limited, particularly in understanding how nurses mediate between institutional expectations and cultural realities. The lack of systematic research on nurses’ lived experiences with cultural-ethical tensions in ACP represents a significant knowledge gap that hinders the development of culturally responsive frameworks. As key advocates, cultural interpreters, and emotional support providers—not merely ACP implementers—nurses’ insights are essential for effective and ethical practice [14]. Addressing this research shortage is critical for generating evidence-based strategies that bridge ethical requirements with cultural realities, ultimately improving ACP outcomes and nursing standards in multicultural healthcare systems. Therefore, this study aims to analyze nurses’ experiences of ethical challenges in ACP implementation within Chinese healthcare contexts, focusing on how cultural norms, ethical dilemmas, and communication barriers intersect to shape nursing practice. By developing a conceptual framework, this research provides a foundation for culturally sensitive ACP strategies informing nursing education and healthcare policy.

To explore and analyze the cultural and ethical challenges faced by nursing professionals implementing ACP in China, with a focus on how cultural norms and professional practices influence end-of-life decision-making.

The study employed a qualitative analysis to explore the responses to three open-ended questions from a nationwide cross-sectional online survey conducted among nursing professionals [15] and the questionnaire has been published elsewhere [16]. This study was conducted between December 2021 and January 2022, utilizing an electronic questionnaire administered via an online survey platform. The study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines [17], with detailed information provided in the supplementary file.

Nursing professionals from oncology hospitals across 22 provinces, 4 municipal cities, and 5 autonomous regions in China participated in the study.

Inclusion criteria included hold a valid nursing qualification, have at least one year of experience in an oncology hospital, and be willing to voluntarily participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included nursing students, visiting scholars in oncology hospitals, and individuals with speech or language impairments.

Participants responded to three open-ended questions designed to capture their perspectives on ACP implementation: (1) Does hospital policy influence your practice of communicating ACP documents with inpatients? (2) How does communicating ACP with oncology patients differ from communicating with other patients? (3) Based on your experience, please list 3–5 major barriers to ACP discussions. The responses to these inquiries constituted the core focus of this study.

The research team consisted of five researchers collaborating on data analysis. The primary researcher, a female PhD specializing in qualitative methods, oncology nursing, and advance care planning consultancy in Taiwan, conducted the text transcription. A female nursing professor and a male physician, both expertise in qualitative research. The coding process was independently performed by the primary researcher and the physician, while the professor cross-validated the codes through discussion. An external lecturer in qualitative methodology provided oversight and critical feedback from outside the end-of-life care context, enhancing reflexivity and minimizing bias. Independent reviews and analyses were conducted to ensure consistency and accuracy, enriching the study with diverse perspectives.

Data collection utilized an online questionnaire distributed via quick response codes (QR codes) to 32 oncology hospitals’ nursing departments, with support from the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association Oncologic Nursing Committee, aiming to include institutions across geographic and administrative diversity (provincial, municipal, and autonomous regions). Following institutional approval, department heads disseminated QR codes and instructions through WeChat work groups. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling across oncology hospitals and professional nursing networks. Electronic informed consent was obtained prior to participation, and participants were informed of the study’s purpose and researchers’ affiliations. There was no prior relationship between researchers and participants. The open-ended questions were designed to elicit participants’ perceptions of cultural, ethical, and communicative challenges in ACP. The three open-ended questions were developed based on a review of relevant literature, expert consultation, and the clinical experience of the research team. The questionnaire was previously pilot tested with a small group of oncology nurses (n = 28) to ensure clarity and relevance. Detailed items have been published elsewhere [16]. All questions required completion before submission. The online format ensured privacy, with no non-participants present during completion. Responses were text-based; no interviews, recordings, or field notes were taken. The survey took approximately 15–20 min to complete. Data on non-participation (e.g., survey views without completion) were not captured by the online platform and thus could not be reported.

All questionnaire responses were initially exported from the online platform and screened for completeness. Data cleaning was performed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Version 2019) to identify and resolve any inconsistencies or anomalies in the dataset. Open-ended responses were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s six-step thematic analysis framework [18]. Thematic analysis was selected for its methodological rigor, flexibility, and systematic approach to identifying patterns in large qualitative datasets [19]. Widely applied in healthcare research, this method enables theoretical adaptability while elucidating cultural and ethical dimensions of ACP implementation, aligning with the study’s objectives. Two independent researchers (YAS and CW) conducted the initial coding process to identify preliminary themes. They first familiarized themselves with the data through repeated reading, then generated initial codes independently. The codes were subsequently collated into potential themes, which were reviewed and refined through iterative discussion between the researchers. Themes were continually refined through review of raw data excerpts to ensure coherence and representativeness.

To ensure analytical rigor, discrepancies in coding and theme identification were resolved through consensus meetings with a third researcher (QL). The final themes were defined and named through collaborative discussion. Data saturation was continuously assessed throughout the analysis process; no new themes or significant new insights emerged from the data analysis, indicating that theoretical saturation was achieved. To enhance trustworthiness, member checking was conducted with a subset of participants to validate the interpretation of their responses.

Interrater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. A kappa value of 0.85 was achieved, indicating strong agreement between coders. Representative quotes were selected to illustrate each theme, and these were translated from Chinese to English by a bilingual researcher (JHD), with back-translation performed to ensure accuracy.

Data saturation was assessed during the coding and theme refinement stages by the core analysis team. Saturation was considered reached when no new codes or themes emerged from the final 10% of responses reviewed independently by two coders (YAS and CW).

The Peking University biomedical ethics committee approved of the study (IRB00001052-21069). Participation was completely optional, with interested nurses accessing the survey link and providing informed consent.

A total of 838 (46.6%) out of 1800 invited participants completed both the demographic questionnaire and the open-ended questions. Most participants were female (97.4%, n = 816), and the main workplace was medical wards (38.5%, n = 323). Very few (15.0%, n = 126) participants reported receiving ACP training. Table 1 contains further information on the demographic and professional characteristics of the participants. From the analysis, three categories and six themes emerged from the data. Table 2 shows the ethical challenges identified by nurses. Fig. 1 reveals a coding tree illustrating the hierarchical relationship between categories, themes, and codes.

The finding revealed that cultural factors, particularly “filial piety”, significantly influenced ACP decisions. Among all open-ended responses, 15.6% (n = 291) mentioned filial piety as a key influencing factor in decision-making. The traditional concept of filial piety often led families to dominate medical decision-making, thereby limiting patient autonomy. Specifically, 141 responses mentioned that “families (children) were reluctant to discuss these issues with the patient”, reflecting a deep-rooted belief in the duty to provide all possible care. Some responses (n = 38) suggested that initiating ACP discussions implied a failure to provide adequate care. This belief further led to 73 responses mentioning that “patients were often unaware of their true medical condition”, as families believed that protecting patients from the “shock” of their illness was a sign of filial piety. Additionally, N325 response indicated that “patients often delegated medical decision-making to their families (such as spouses or children), prioritizing family harmony over personal involvement.”

The “taboo of death” emerged as another significant cultural barrier to ACP decision-making. The responses revealed a widespread avoidance of death-related discussions among families (n = 62), with a prevalent preference for life-prolonging treatments (n = 56). This behavioral pattern reflects a cultural sensitivity and avoidance of death-related topics rather than being solely based on the patient’s actual preferences. Furthermore, 23 responses indicated that nursing professionals themselves were influenced by the “taboo of death,” avoiding initiating discussions about death-related issues. This phenomenon may be attributed to the permeation of cultural norms into professional practices or may reflect deficiencies in nursing professionals’ communication skills or institutional support. Notably, the “taboo of death” was not merely about avoiding discussions; it also manifested as a strong belief in the sanctity of life. N129 response mentioned the Chinese saying “it’s better to live a miserable life than to die,” reflecting a cultural belief that prioritized life preservation, even at the expense of quality of life. Consequently, families were more inclined to opt for aggressive treatments rather than pursuing palliative care options that might align more closely with the patient’s true wishes.

A significant ethical dilemma in decision-making is the “neglect of patient preferences.” Responses indicated that healthcare teams and families often prioritize aggressive medical interventions over the patient’s expressed wishes. As stated in 32 responses, families were “reluctant to discuss these issues with the patient,” resulting in the patient’s voice being marginalized in decision-making. Additionally, 3 responses highlighted that even at the end of life, families often pursued “aggressive life-prolonging measures,” indicating a strong desire to prolong life that often superseded the patient’s actual wishes. Furthermore, patients’ ability or opportunity to express their preferences was limited, as evidenced by 18 responses indicating that patients were unable to articulate their preferences due to their medical condition, cultural background, or lack of information.

Another significant ethical dilemma is the “conflict between medical technology and ethics.” Respondents highlighted the critical challenges healthcare teams encounter when navigating end-of-life medical interventions, particularly the complex decision-making processes surrounding “uncertain rescue timing” and “appropriate moments for patient-family discussions”. This inherent uncertainty underscores the ambiguous boundaries between technological application and ethical deliberation in clinical practice. Specifically, seven responses critically examined whether “medical interventions genuinely respect patient quality of life”, emphasizing potential ethical dilemmas arising from excessive technological dependency. Moreover, three responses addressed “end-of-life medical resource allocation”, illuminating the profound ethical considerations required when deploying technological capabilities to make resource utilization decisions.

A significant practical challenge in patient-provider communication is the “information asymmetry and power dynamics”. As indicated by 26 responses, the authoritative stance of nursing professionals often limits patients’ and their families’ access to information. This power dynamic not only undermines patients’ right to know but also weakens their proactive involvement in decision-making. The direct consequence of such information asymmetry is evident in 58 responses highlighting patients’ “insufficient understanding of their own medical condition,” and N525 even replies: “Some Times, doctors only talk to the family in a separate room; we are not even invited.” This may be attributed to inadequate information provision by nursing professionals or deliberate concealment by families. Furthermore, 42 responses mentioned “poor communication among physicians, nurses, patients, and families,” indicating a breakdown in multi-party communication that exacerbates information asymmetry. Additionally, 16 responses pointed out the “inability of nursing professionals to communicate with patients in a timely and appropriate manner,” suggesting a reliance on unidirectional information transmission rather than interactive and transparent communication.

The “family-centered decision-making” (33.1% of codes) further complicated boundary ethics in nursing practice, as nurses had to navigate conflicting expectations.179 mentioned “fearing that discussing the situation would upset the patient,” while 106 noted families were hesitant to discuss sensitive topics to avoid “burdening the patient.” Furthermore, 86 responses mentioned that “families were reluctant to discuss these issues with the patient,” often motivated by a desire to “protect” by withholding information or minimizing discussions. This protective behavior sometimes extended to information control, as seen in 29 responses where families explicitly stated that they “did not want the patient to know about their cancer diagnosis.” This highlights the systemic issue of power imbalances in ACP discussions, where patients’ voices are often marginalized.

The thematic analysis of nurse responses revealed a dynamic interplay among cultural norms, ethical dilemmas, and communication challenges in the implementation of ACP within the Chinese healthcare context (Fig. 2). This figure illustrates the interaction and overlaps of these three domains, generating specific implementation challenges at their intersections.

The cultural norms domain encompasses two primary themes: filial piety and death-related taboos. These deeply ingrained cultural values significantly influence attitudes towards end-of-life discussions among families and healthcare professionals. The ethical dilemmas domain highlights two core challenges: the disregard for patient preferences and the conflict between medical technology and ethical principles. The communication challenges domain focuses on information asymmetry, power dynamics, and family-centered decision-making, all of which complicate transparent communication.

Furthermore, based on participant responses, the researchers identified key areas where these domains intersect. At the intersection of cultural norms and ethical dilemmas, the tension between familial decision-making authority and patient autonomy is paramount. When cultural norms meet communication challenges, death-related taboos pose significant barriers to open dialogue. Between ethical dilemmas and communication challenges, information control practices conflict with patients’ rights to understand their medical condition.

At the core of this dynamic interaction diagram lies the convergence of all three domains, representing the central challenge for nurses implementing ACP in the Chinese context: developing culturally sensitive ethical nursing practices that balance respect for traditional values with the protection of patient rights. This conceptual framework provides a foundation for developing targeted interventions that address these specific intersections, rather than treating each challenge in isolation.

This study revealed three interrelated domains—cultural norms, ethical dilemmas, and communication challenges—that shape nurses’ ACP implementation experiences in China (Fig. 2). These findings, while culturally specific, parallel challenges in other Asian societies.

Family-centered decision-making, rooted in Confucian filial piety, represents the predominant cultural barrier challenging Western ACP frameworks and creating tension between collective family responsibility and individual patient autonomy. Within this framework, familial interests and emotional considerations are paramount, directly influencing healthcare and end-of-life choices [20]. This cultural paradigm fundamentally transforms the nurse’s therapeutic relationship and redefines advocacy roles in collectivist healthcare settings. This aligns with Zhai et al. [21] that oncologists commonly discuss disease progression and treatment options with families rather than patients, leading to a form of ‘closed awareness of dying’. However, distinct from Glaser and Strauss’s concept, this lack of communication often stems from familial control over medical information and decisions [22]. The resultant information gatekeeping creates a complex ethical landscape where nurses must navigate between respecting cultural values and fulfilling professional obligations to patient advocacy [23]. This practice creates resistance to ACP, which inherently emphasizes truth-telling and patient autonomy [24]. These findings suggest the need for culturally adapted ACP models that can accommodate family-centered values while preserving opportunities for patient input. This model creates boundary conflicts for nurses experiencing dual loyalties between institutional autonomy policies and family demands for information withholding, highlighting neglected mediator roles and necessitating boundary management strategies in nursing education and supervision.

Death taboo, prevalent across Western and Asian cultures, represents a fundamental obstacle to ACP implementation beyond mere communication barriers—it challenges the philosophical foundations of ACP. This reflects traditional Chinese values discouraging life-death discussions due to perceived inauspicious consequences [11]. The taboo creates institutional environments systematically avoiding death preparation [25], potentially compromising end-of-life care quality. Consequently, practitioners defer to families in condition disclosure [10], marginalizing patients in end-stage decisions and compromising their autonomy [25]. These findings necessitate institutional policy changes. Death taboo requires systematic interventions including multidisciplinary death education for healthcare professionals and communities [26]. Institutions should implement standardized documentation protocols capturing patient preferences through family mediation and establish ethics review mechanisms for cases were traditional values conflict with modern healthcare ethics.

The intersection of cultural norms with communication challenges reveals the complex dynamics that nurses must navigate in ACP implementation. Patient autonomy in end-stage decision-making is understood differently across cultures, especially in Asian contexts. Rather than viewing these cultural differences as barriers to overcome, our findings suggest the need for a paradigmatic shift toward culturally responsive ACP models that can accommodate diverse conceptualizations of autonomy while maintaining ethical integrity. The prevalence of overtreatment in end-stage care is partially attributable to unrealistic familial expectations regarding disease progression [27], which complicates healthcare professionals’ efforts to facilitate ACP. Concurrently, healthcare professionals, irrespective of their practice location, often encounter ethical dilemmas in balancing respect for familial wishes with the imperative to safeguard patient autonomy [14, 25]. These dynamics underscore the need for structured ethical decision-making frameworks that can guide nurses through culturally complex scenarios. From a boundary ethics perspective, nurses frequently navigate ethical gray areas where institutional regulations, professional codes of conduct, and cultural norms diverge. This ethical ambiguity requires comprehensive support systems that acknowledge nurses’ unique position as cultural mediators and equip them with practical tools for ethical decision-making in multicultural contexts. These findings have practical implications for nursing education and institutional policy. Nursing curricula should incorporate training in ethical decisionmaking across cultural contexts, and hospitals should implement support mechanisms for nurses managing boundary dilemmas in ACP communication.

The study’s results highlight the global imperative to enhance public understanding of advance care planning and end-of-life ethical considerations. Based on the conceptual model, the conceptualization of the challenges of implementing advance care planning (ACP) provides a practical framework for understanding and responding to the complex dynamics that nurses encounter in clinical practice. The intersections of the model represent critical intervention points where targeted strategies can have the greatest impact. Future interventions must adopt a systems-level approach that addresses cultural competency across institutional policies, educational curricula, and clinical practice guidelines.

In terms of promoting patient-centered communication, the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines recommend culturally appropriate communication strategies to facilitate ACP [28]. Flexible communication balances patient autonomy with cultural expectations, reducing family resistance and building trust between healthcare professionals, patients, and families. Research shows family involvement in collective decision-making effectively balances ethical obligations with cultural norms [29]. This approach aligns with the model’s central recommendation for culturally sensitive nursing ethics, honoring Chinese family decision-making traditions while protecting patients’ medical decision rights.

This study highlights ACP implementation specificity in Chinese cultural context compared to Western studies. Family decision-making models have stronger influence in Chinese societies, necessitating cultural adaptations when adopting Western approaches. Future research should validate and refine the conceptual model, exploring integrating family participation while maintaining patient autonomy, and develop culturally appropriate ACP implementation models.

This study’s focus on the Chinese cultural setting limits the generalizability of findings to other regions. Ethical challenges in ACP implementation vary across healthcare systems and cultural norms, requiring further cross-cultural research. Several methodological limitations warrant acknowledgment. This study lacks methodological triangulation, as it relies on a single data source without integrating multiple methods, perspectives, or frameworks, which may limit the comprehensiveness and validity of the findings. While the conceptual model identifies key relationships among cultural norms, ethical dilemmas, and communication challenges, it may not capture the complexity of these interactions. The use of open-ended survey responses, though suitable for broad data collection, may constrain the depth of insight; this methodological approach limits the ability to explore nuanced experiences and underlying mechanisms that drive nurses’ ACP implementation challenges; future studies should consider in-depth interviews or focus groups. Furthermore, the study lacks member checking or participant validation of findings, which could have enhanced credibility and ensured accurate representation of nurses’ experiences. The absence of longitudinal data collection also limits understanding of how ACP implementation challenges evolve over time or vary across different clinical contexts. Moreover, given the voluntary and anonymous nature of online survey distribution, self-selection bias may have occurred, potentially overrepresenting nurses with stronger interest or familiarity with ACP.

This study elucidates the intricate interplay among cultural values, healthcare systems, and patient autonomy within ACP. The conceptual model of cultural norms, ethical dilemmas, and communication challenges provides a framework for understanding the systematic barriers to ACP implementation in the Chinese context. Cultural contexts profoundly influence end-of-life decision-making, posing challenges to the universal application of Western bioethical principles. Nursing educators should integrate cultural competence, ethical reasoning, and communication training into curricula. Healthcare administrators should develop policies that clarify nurses’ roles in ACP and support ethical consultations. Policy makers should promote ACP frameworks that align with cultural values while protecting patient autonomy. As the model suggests, culturally sensitive implementation requires flexible strategies that address the intersections between decision-making processes, family roles, and belief systems. Future research should explore actionable interventions that align ethical imperatives with cultural traditions, informing inclusive and effective ACP practices.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors would like to thank the Oncology Nursing Professional Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association for their tremendous support of this study, as well as every participant who took part in this study.

This work was supported by the “National Natural Science Foundation of China (72174011)”. National Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (2023QN08002), Inner Mongolia Medical University General Project (YKD2022MS005), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region High-Level Talent Research Support Fund (186), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region talent development Fund (2023), Introduction of High-level Talents Foundation of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China (2024), and Inner Mongolia Medical University Affiliated Hospital High-level Talent Project-Continuation Fund (2025).

The study was approved by the Peking University Biomedical Ethics Committee (IRB00001052-21069) and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study rigorously adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Shih, YA., Wang, C., Ding, J. et al. Cultural and ethical barriers to implementing end-of-life advance care planning among oncology nursing professionals: a content analysis of open-ended questions. BMC Med Ethics 26, 96 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-025-01261-x