African Women at the Negotiation Table: The Forgotten Female Diplomats Who Shaped Post-Independence

The political history of Africa’s independence is often told through the speeches, decisions, and handshakes of its founding fathers. Figures like Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, and Jomo Kenyatta dominate historical narratives, their images fixed in black-and-white photographs from the 1960s. Yet this telling is incomplete.

Alongside these men were women who were diplomats, negotiators, advisers, whose contributions were equally critical to the shaping of post-independence African politics.

These women were present at negotiation tables in capitals. They lobbied for recognition of new nations, brokered trade and peace agreements, and represented their countries in forums that determined Africa’s place in the global order.

Despite their influence, their names have too often been footnotes in the historical record, overshadowed by the male-dominated political culture of their time.

Independence and the Gendered Nature of Diplomacy

The decades between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s marked an unprecedented wave of African independence. More than 40 nations emerged from colonial rule during this period, each facing the urgent task of establishing stable governance and forging diplomatic ties.

Diplomacy was not a ceremonial duty; it was essential for survival in a world still shaped by the Cold War, where aligning with the right partners could mean economic aid, security guarantees, or international legitimacy.

Yet, the structures of both colonial and postcolonial governance were deeply patriarchal. Diplomatic services and foreign ministries were male-dominated, often excluding women outright or confining them to administrative roles.

For an African woman to occupy a negotiating seat during these years meant challenging cultural norms, political skepticism, and global prejudices simultaneously.

The Women Who Sat at the Table and Sometimes Led It

Photo Credit: Google

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

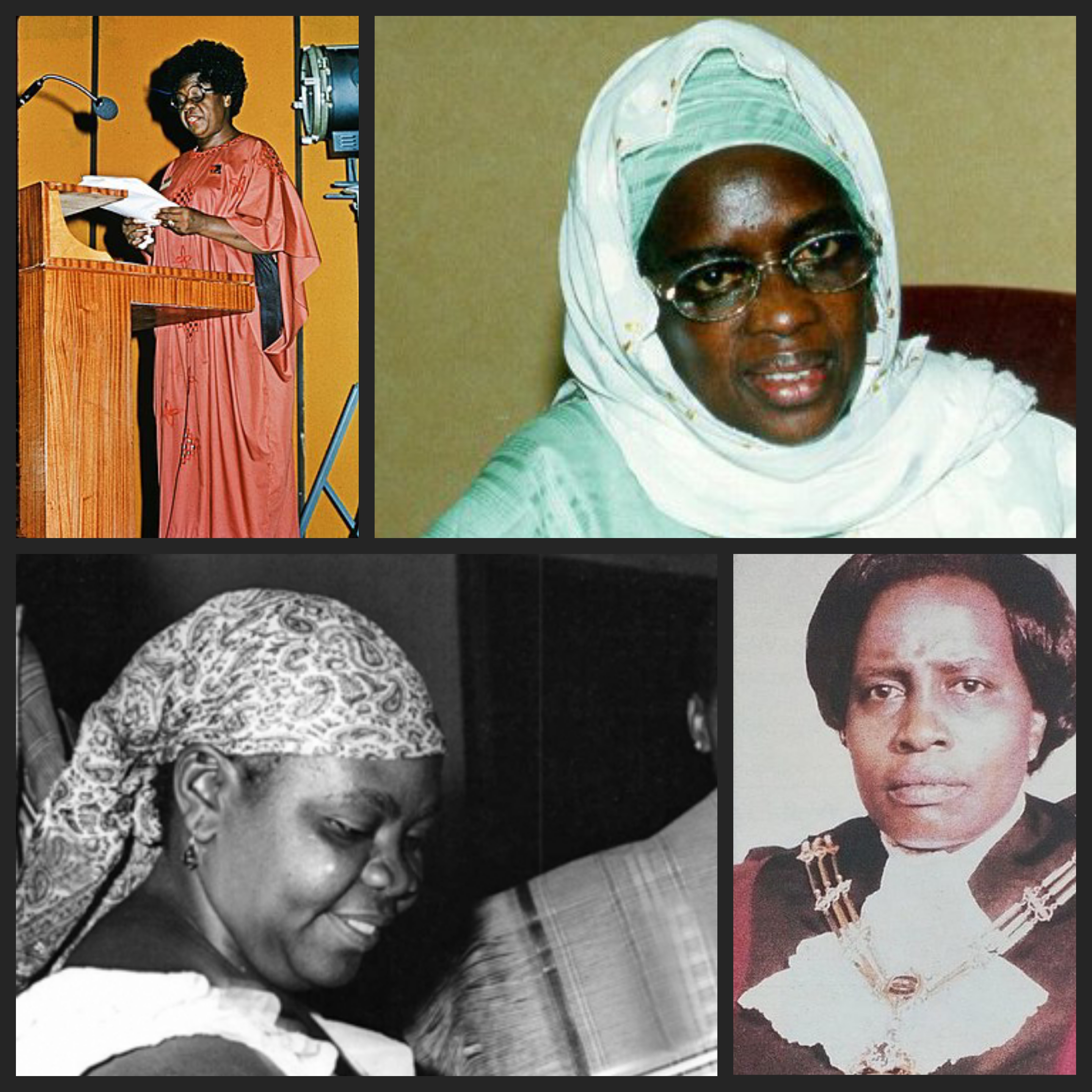

Angie Elizabeth Brooks (Liberia)

One of the most remarkable African diplomats of the 20th century, Angie Elizabeth Brooks

broke multiple barriers. In 1969, she became the first African woman to serve as President of the United Nations General Assembly.

Representing Liberia, Brooks worked at the highest levels of diplomacy during a period when newly independent African states were navigating Cold War pressures.

She was a vocal advocate for African unity, the dismantling of apartheid, and the right of nations to chart their own paths without external interference. Her leadership at the UN elevated Africa’s diplomatic profile and demonstrated that African women could command the same respect as their male counterparts in global politics.

Photo Credit: Google

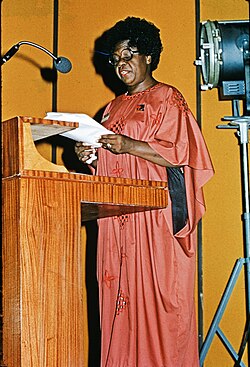

Aïssata Kane (Mauritania)

Aïssata Kane was Mauritania’s first female minister and an early champion of women’s education and political participation. Her diplomatic influence extended beyond her ministerial duties as she represented Mauritania in international negotiations on development and trade in the 1960s and 1970s.

Kane’s work was often met with resistance, particularly from male colleagues who saw her role as symbolic rather than substantive. Yet she consistently proved her strategic value, steering discussions that helped integrate Mauritania into the broader African and Arab political spheres.

Photo Credit: Google

Bibi Titi Mohamed (Tanzania)

While Bibi Titi Mohamed is often remembered for her role in Tanzania’s independence movement, her diplomatic contributions after independence are less recognized. As a close political ally of President Julius Nyerere, she played an informal but important role in shaping Tanzania’s foreign policy, especially in relation to liberation movements in southern Africa.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Though she did not hold a formal ambassadorial post, Bibi Titi acted as an intermediary in regional discussions, helping to build solidarity between Tanzania and anti-colonial movements in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and South Africa.

Photo Credit: Google

Margaret Kenyatta (Kenya)

Margaret Kenyatta, daughter of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, was appointed as Kenya’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations in the late 1970s. Her diplomatic work focused heavily on gender equality, global peace initiatives, and development policy.

She was instrumental in preparations for the 1985 UN World Conference on Women in Nairobi, which became a milestone in the international women’s rights movement. Her tenure at the UN strengthened Kenya’s image as a leader in advocating for gender and development issues on the world stage.

The Invisible Work of Women in Diplomacy

Not all influential female diplomats of the post-independence period had official titles. Many worked behind the scenes as advisers, speechwriters, translators, and cultural envoys.

Some were the wives of political leaders, using their access to foreign dignitaries to shape perceptions and smooth negotiations.

This invisible labour was particularly significant in contexts where formal diplomacy excluded women. These roles allowed women to influence decisions without appearing to threaten male political authority which served as a delicate balance in conservative political cultures.

Challenges in a Male-Dominated Arena

The path for African women in diplomacy was steep and often isolating. They faced gender bias not only within their home governments but also in the international community. Diplomatic events were often spaces of exclusion, where women’s presence was treated as an anomaly.

Additionally, women in diplomacy carried the burden of representing both their countries and the broader cause of women’s political participation. Every misstep was magnified, interpreted not as an individual failing but as proof that women were unsuited for political leadership.

History

Rewind the Stories that Made Africa, Africa

A Journey Through Time, Narrated with Insight.

Their Legacy Today

The work of these women created precedents that allowed later generations to participate more fully in African and global diplomacy. By occupying negotiation tables in the 1960s and 1970s, they challenged stereotypes and demonstrated the strategic advantage of inclusive diplomacy.

Today, African women such as Amina Mohamed (Kenya), Naledi Pandor (South Africa), and Fatou Bensouda (The Gambia) occupy prominent diplomatic positions. Their achievements are part of a legacy built by the women of the independence era.

Yet, despite these advances, women remain underrepresented in Africa’s foreign ministries and ambassadorial posts. The historical contributions of early female diplomats are still insufficiently recognized in academic research, public commemorations, and political discourse.

The Story Continues

The story of Africa’s post-independence diplomacy cannot be told in full without acknowledging the women who shaped it.

From Angie Elizabeth Brooks at the UN to Aïssata Kane in Mauritania and Margaret Kenyatta in New York, these women were not symbolic participants, they were negotiators, strategists, and visionaries.

Their presence at the negotiation table challenged entrenched gender norms and set a foundation for the gradual inclusion of women in African politics and diplomacy. Remembering their work is not just an act of historical justice, it is a reminder that inclusive diplomacy strengthens nations.

In rewriting the story of African diplomacy, these women deserve to be moved from the margins of history to its center where they always belonged.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...