Africa vs. Vaccines: A Tale of Fear or Wisdom?

Imagine the solemn state of Kano in northern Nigeria in the mid‑1990s. Parents carry their feverish children to clinics, hoping for relief. At the same time, a devastating meningitis epidemic sweeps through the region. There is fear, loss, and a sense of abandonment.

In this context, Pfizer arrives with an experimental antibiotic called Trovan. It is said that families were told little. Doctors did not formally receive consent from families. In many cases, the standard treatment offered by Doctors Without Borders was ignored. Soon after, there were deaths and children left with paralysis, brain damage, hearing loss and other lifelong disabilities.

A Nigerian expert panel later concluded the trial was illegal, conducted without real government approval or meaningful parental consent. Five children in the Trovan group died. Six in the control group also died. Many more were severely harmed.

As details became known, outrage spread. In 2007, Kano State sued Pfizer for billions. The case dragged on.

A diplomatic scandal emerged when leaked cables suggested Pfizer had hired investigators to pressure officials through threats of corruption exposure.

Eventually, in 2009, Pfizer settled with Kano State for around $75 million, funding family support and healthcare programs. The company denied wrongdoing.

The widely reported Trovan clinical trial took place not in a remote village but in the city of Kano, specifically at the Infectious Disease Hospital (IDH) in Kano State, Nigeria

Rumors Become Reality: Vaccine Boycotts and the Polio Resurgence

Image Credit: Unsplah

Fast forward to 2003. Memories from the Trovan tragedy are still fresh. In Kano and other northern Nigerian states, religious leaders warn families not to vaccinate children for polio. Rumors spiral that the vaccine is contaminated with anti‑fertility agents, HIV or cancer-causing viruses. The faith leaders, politicians and a general distrust in medicine converge.

Three states, including Kano, Kaduna and Zamfara, suspend polio immunisations entirely. Rates of polio rise dramatically, and Nigeria becomes the epicentre of a plague that spreads to over a dozen African countries as far away as Togo and Ethiopia.

Public health teams are compelled to respond. Vaccines are tested independently. A mass campaign involving 23 countries and 40 million children was launched in early 2005. Southern health authorities work tirelessly to regain trust. It took until the end of 2004 for Kano to relent. By 2016, Nigeria reported its last wild polio case. In 2020, WHO declared Africa polio‑free.

Vaccine Rumors as an Ecosystem

The anthropologist Heidi Larson spent months in Nigeria gathering women’s stories. She listened as mothers asked why authorities seem interested only in certain vaccines when their villages lack clean water, electricity or food.

Some suspect a hidden agenda because rumors of sterilization ring true to them after years of neglect. Others accept vaccination privately, but lack the boldness within patriarchal households to take children to clinics.

Larson describes these rumors as part of a broader ecosystem rather than isolated misinformation. She argues that health interventions must consider those emotional and social roots, not just fact-check scientific claims.

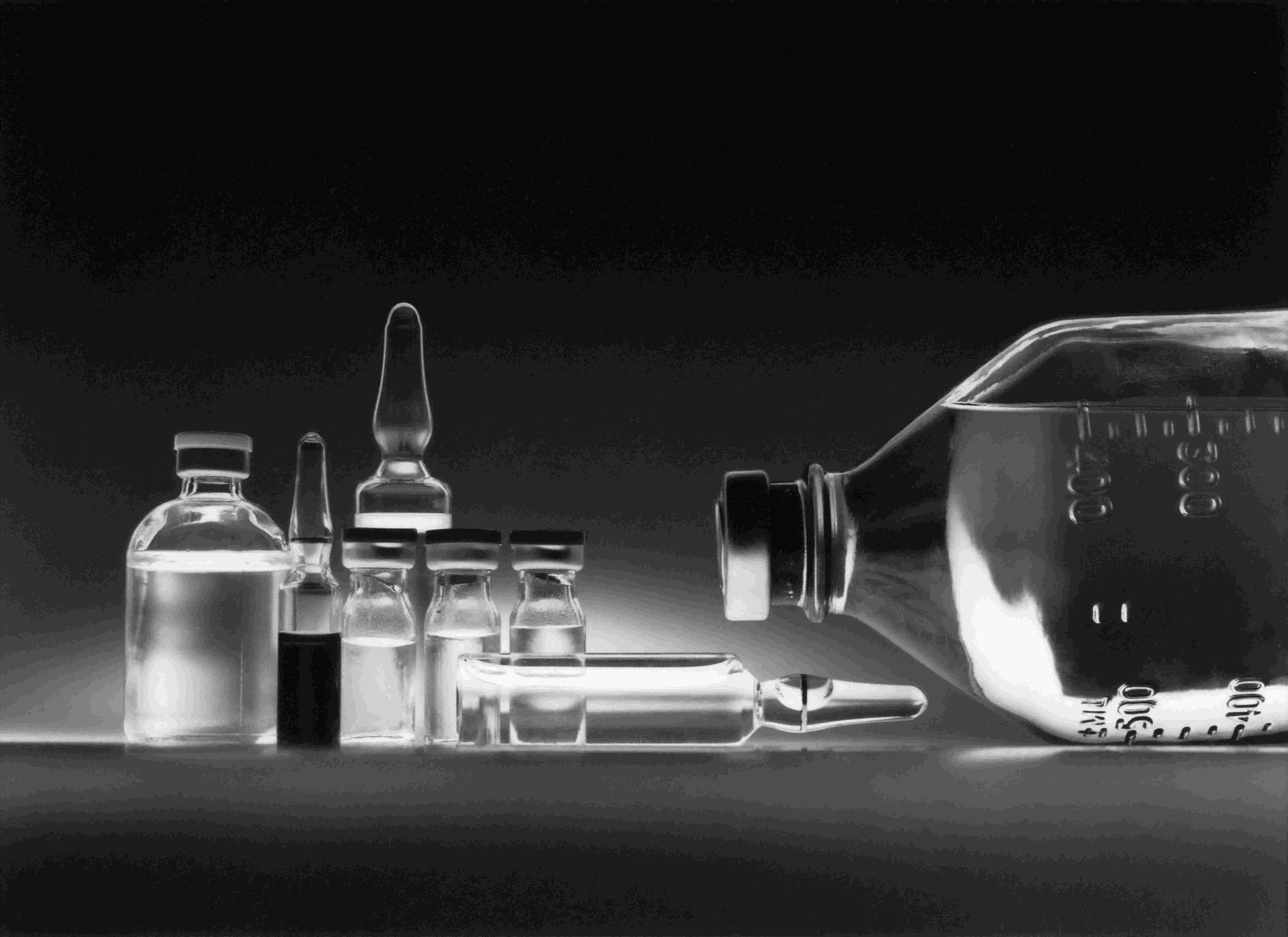

What Has Actually Caused Harm? Known Vaccine Side Effects

Across Africa, most vaccines used are said to be safe. Mild side effects such as injection-site pain, low fever or local swelling are common and expected. However, a few known awry cases include:

The oral polio vaccine can, in very rare instances, cause vaccine-associated paralytic polio, at a rate around one case per 2.7 million doses.

Yellow fever vaccine, used broadly across Africa, has led to a small number of serious neurologic events globally—dozens of cases among hundreds of millions of doses.

COVID‑19 vaccines such as the viral-vectored AstraZeneca vaccine saw reports of clotting complications in some countries, prompting temporary pauses and enhanced safety messaging.

Nevertheless, such reports fuel hesitance.

Why Hesitance Persists

History shapes perception

When children were harmed while being treated for meningitis by Western doctors, suspicion planted deep roots. That legacy fueled the vaccine hesitancy narrative in 2003.Basic needs unmet

Community members questioned why the government and international agencies seemed to prioritize vaccination while failing to address basic necessities such as clean water, nutrition, or healthcare.Political and religious dynamics

Religious leaders and state governments held motives rooted in political distrust. The northern states’ vaccine boycott reflected deeper divisions within a fragile federal system.Communication breakdown

Official announcements were often made in English, an unfamiliar language to many, with a tone that lacked empathy and follow-through. As a result, rumors filled the silence and mistrust grew.

Building Trust Takes Time

Listening matters. Acknowledging past harms, sharing stories, and validating concerns can open dialogue.

Partnerships with local leaders and health workers rooted in respected community networks can improve acceptance.

Safety systems must be transparent. Strong surveillance for adverse events and accessible compensation programs help to rebuild confidence gradually.

Tackling misinformation means engaging online and offline, providing context, and humanizing science.

Conclusion

Image Credit: Unsplash

Modern medicine, as we know it today, is the product of a rich tapestry woven from knowledge and innovation across every corner of the world. The mathematical theories and astronomical insights from the scholars of the Middle East laid the groundwork for modern diagnostics and treatment calculations. Africa’s ancient herbal medicine traditions contributed invaluable knowledge about natural remedies and healing practices that continue to inspire new pharmaceuticals.

The manufacturing expertise and meticulous craftsmanship of China have long enabled the production and distribution of medical instruments and medicines on a vast scale.Without the invention of the microscope—thanks to pioneers in Europe—our understanding of pathogens and cells would remain limited.

Each breakthrough, discovery, and practice builds on the wisdom and effort of countless cultures and peoples. Medicine is truly a global endeavor, one that could not exist without the collective contributions of humanity across time and geography.

Vaccine hesitancy in Africa is not a matter of ignorance but of deeper wounds, systemic neglect, and fragmented trust. Yet the real crisis has been broken trust—the sense that health interventions come without explanation or accountability.

And so that raises another question: Why can’t we make our own vaccines?

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

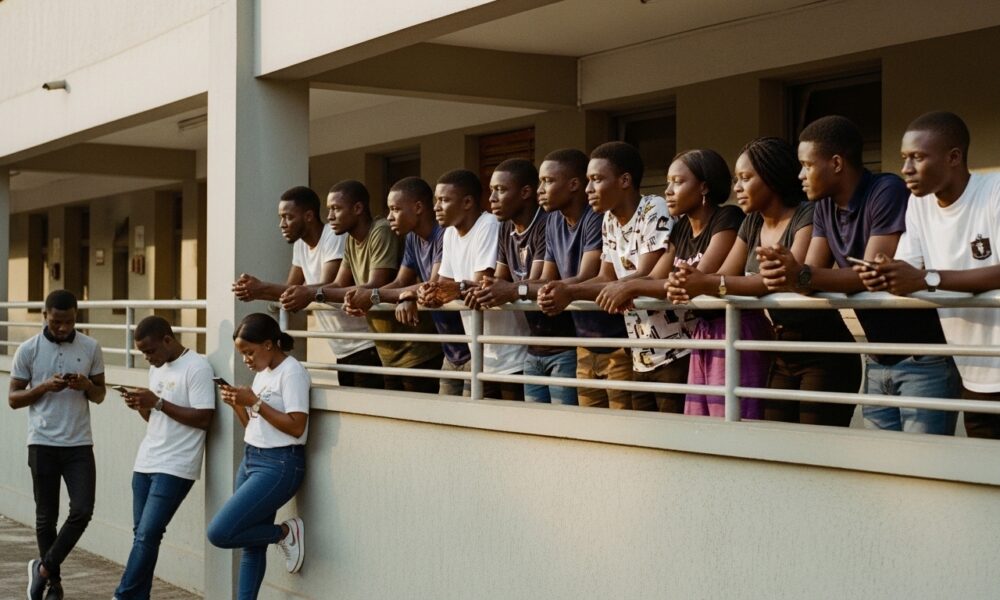

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...