A World Unwell: Unpacking the Systemic Failures of Global Health

Despite monumental advancements in medical science and technology, the global health system appears increasingly fragile and fundamentally unequal.

Recent crises, from the COVID-19 pandemic to persistent disease outbreaks, have exposed the deep cracks in its foundation.

SOURCE: Google

This systemic health crisis, characterized by underfunded infrastructure, stark inequities in access to care, and a struggle to adapt to new threats.

These failures disproportionately affect vulnerable populations and pose a significant threat to collective human security and economic stability. A new era of collaborative and equitable health solutions is urgently needed.

Primary Indicators of Systemic Strain

The global health system exhibits multiple primary indicators of strain, revealing a system that is struggling to cope. Vaccine inequity stands out as a stark example.

SOURCE: Google

The recent pandemic highlighted a "vaccine apartheid," where high-income countries secured the vast majority of vaccine doses while low-income nations struggled for access.

This disparity prolonged the pandemic's economic and social impact, underscoring a critical failure of global governance. In a similar vein, persistent outbreaks of diseases like Ebola and measles continue to challenge health systems, often in regions with weak infrastructure.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has noted a concerning rise in measles cases due to a decline in routine vaccinations, a clear sign of systemic fragility.

Furthermore, the global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is a growing crisis. NCDs like cardiovascular disease, cancer, and diabetes now account for over 70% of all deaths worldwide.

This rising burden puts immense pressure on health systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries that lack the resources for long-term care. Simultaneously, a global mental health crisis is unfolding, exacerbated by economic stress, social isolation, and conflict.

The World Health Organization estimates that approximately one in eight people worldwide live with a mental disorder, yet mental health services remain severely underfunded and inaccessible in many parts of the world.

These interconnected crises are a clear sign that the current global health architecture is failing to meet the needs of the population.

Socio-Economic and Geopolitical Disparities

Socio-economic disparities and geopolitical dynamics are not just factors in health inequality; they actively exacerbate it. Within nations, wealth and education levels are directly linked to health outcomes.

SOURCE: Google

Lower-income communities often have limited access to quality healthcare, nutritious food, and safe housing, leading to a higher prevalence of chronic diseases and shorter life expectancies.

The economic stress resulting from poverty can also contribute to a higher burden of mental health issues and substance abuse. This inequity is a key driver of health disparities.

On a global scale, geopolitical dynamics play a crucial role. Conflicts, trade policies, and political instability can disrupt health supply chains, displace populations, and destroy essential infrastructure.

A report by The Lancet highlights how geopolitical tensions can hinder international cooperation, leading to delays in humanitarian aid and vaccine distribution.

These dynamics also influence research and development priorities, often favoring diseases prevalent in high-income countries while neglecting tropical or neglected diseases that primarily affect low-income regions.

The result is a system where a person's health is often dictated more by where they live and their economic status than by their inherent needs.

Underfunding, Governance, and Infrastructure

Underfunding, weak governance, and inadequate infrastructure are the foundational cracks hindering effective health responses, particularly in low-income regions.

SOURCE: Google

Many nations allocate a disproportionately low percentage of their GDP to healthcare, leading to a chronic shortage of doctors, nurses, and medical supplies.

This underfunding is a major reason why basic health services, like routine vaccinations and maternal care, are not universally available.

A 2023 study found that many low-income countries need to increase their health spending by at least 150% to meet basic healthcare targets.

Beyond a lack of funds, weak governance and corruption can cripple health systems, leading to inefficient resource allocation and a lack of accountability. Inadequate infrastructure is another critical challenge.

Many health facilities in low-income regions lack reliable electricity, clean water, and the necessary equipment to treat patients effectively. This systemic weakness means that even when a new medical technology or treatment is developed, it often cannot be effectively implemented in the regions where it is most needed.

The combination of these factors creates a vicious cycle of poor health outcomes and stunted economic development.

Emerging Threats and Unprecedented Pressure

Emerging global challenges are putting unprecedented pressure on already-strained health systems worldwide. Climate change is a major threat, impacting human health through extreme weather events, the spread of infectious diseases via new vectors, and food and water insecurity.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has documented how rising temperatures are expanding the geographic range of diseases like malaria and dengue fever, placing new populations at risk.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is also a silent pandemic, with drug-resistant infections becoming a leading cause of death.

The overuse of antibiotics in both humans and agriculture is accelerating the evolution of superbugs, threatening to render common infections untreatable and reversing decades of medical progress.

SOURCE: Google

Increasing urbanization presents another set of challenges. While cities can be centers of economic growth, rapid and unplanned urbanization can lead to overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and air pollution, all of which contribute to the spread of infectious diseases and the rise of NCDs.

The concentration of people in urban centers also makes them hubs for disease outbreaks, with the potential for rapid global dissemination.

These emerging threats are a reminder that the health system must become more resilient, proactive, and interconnected to handle a new era of complex, multi-layered risks.

Economic and Social Consequences

The potential long-term economic and social consequences of a failing global health system extend far beyond immediate mortality rates. Economically, a persistent state of poor health can lead to a significant decline in labor productivity and a reduction in a nation's human capital.

The World Bank has estimated that the economic cost of the COVID-19 pandemic alone, including lost output and increased poverty, will be substantial and long-lasting.

Chronic illnesses and disease outbreaks can divert resources from other critical sectors, like education and infrastructure, stifling economic development.

Socially, a failing health system erodes public trust in institutions and can exacerbate social inequalities, as the wealthy can afford to access private care while the poor are left with inadequate options. This deepens social divisions and can contribute to political instability.

A society that cannot protect the health of its citizens is ultimately a fragile one. The mental health crisis, in particular, has long-term social consequences, impacting family stability, educational attainment, and a sense of community well-being.

A resilient global health system is therefore a prerequisite for both economic prosperity and social cohesion.

Urgently Needed Policy Shifts and Innovative Models

To build a more equitable, resilient, and proactive global health architecture, innovative models and bold policy shifts are urgently needed.

A key shift involves moving away from a reactive, crisis-driven approach to a proactive one focused on pandemic preparedness and prevention.

This requires significant investment in public health infrastructure at the local level and the establishment of a global health security fund to rapidly respond to outbreaks.

Furthermore, international collaborations must be strengthened. The creation of a new Pandemic Treaty under the WHO is a step in the right direction, aiming to improve international cooperation on health crises and ensure more equitable access to vaccines and treatments.

Innovative financing models, such as impact bonds and blended finance, are also needed to attract private capital for health infrastructure in low-income regions.

The integration of technology, like AI for disease surveillance and mobile health platforms for last-mile care, offers a path to leapfrog traditional infrastructure barriers.

Finally, a greater focus on community-led initiatives and social justice is required to address the root causes of health inequalities and ensure that a healthy future is accessible to everyone, not just a privileged few.

You may also like...

How Technology, Equity, and Resilience are Reshaping Global Healthcare

The global healthcare system is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by technological leaps, a renewed focus on ...

A World Unwell: Unpacking the Systemic Failures of Global Health

From recurring pandemics to glaring inequities, the global health system is under immense strain. This article explores ...

Sapa-Proof: The New Budget Hacks Young Nigerians Swear By

From thrift fashion swaps to bulk-buy WhatsApp groups, young Nigerians are mastering the art of sapa-proof living. Here ...

The New Age of African Railways: Connecting Communities and Markets

(5).jpeg)

African railways are undergoing a remarkable revival, connecting cities, boosting trade, creating jobs, and promoting gr...

Digital Nomadism in Africa: Dream or Delusion?

For many, networking feels like a performance — a string of rehearsed elevator pitches and awkward coffee chats. But it ...

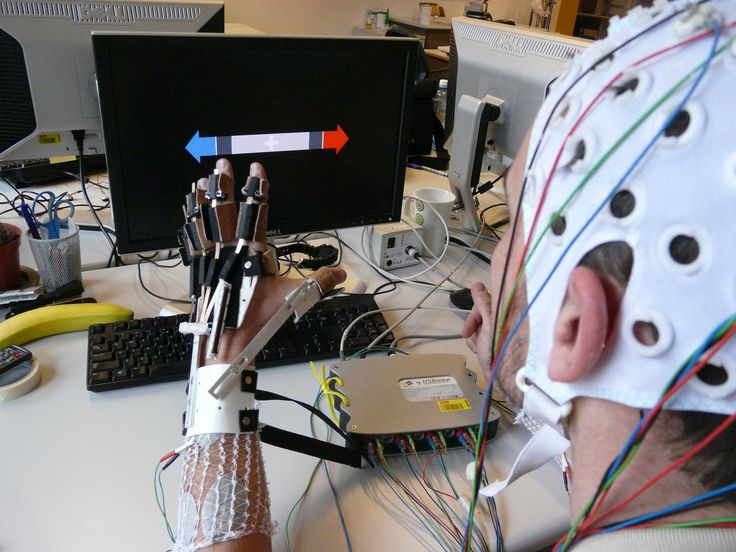

The Ethics of Brain-Computer Interfaces: When Technology Meets the Mind

This piece redefines networking as a practice rooted in curiosity, generosity, and mutual respect, sharing stories from ...

Carthage: The African Power That Challenged Rome

Long before Rome became the undisputed master of the Mediterranean, it faced a formidable African rival whose power, wea...

Africa’s Oldest Seat of Learning: The Story of al-Qarawiyyin

Long before Oxford or Harvard opened their doors, Africa was already home to a seat of learning that would shape global ...