A Forgotten Experiment Led to the World’s First Antibiotic

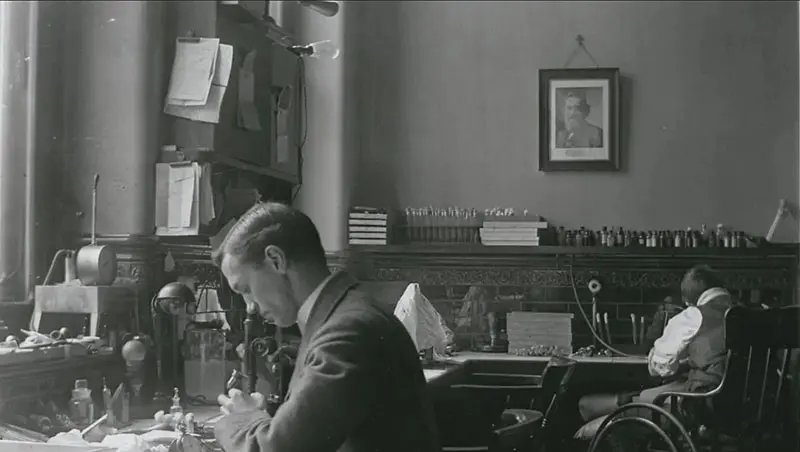

The Messy Lab That Changed Medicine

In 1928, St. Mary’s Hospital, Alexander Fleming stumbled upon something that changed the world. Fleming, a dedicated scientist and doctor, spent his days studying bacteria that caused serious infections in humans. These bacteria, especially Staphylococcus were feared because even small cuts or scratches could lead to life-threatening infections. Hospitals at the time had few tools to fight these infections and doctors often watched helplessly as patients succumbed to diseases that today seem easily treatable.

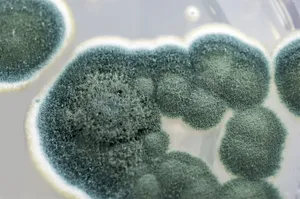

Fleming’s lab was far from pristine. Petri dishes filled with bacteria cluttered the benches, some neatly stacked, others forgotten in the rush of daily experiments. One day, Fleming returned from a short trip and noticed a dish that had been overlooked for several days. Unlike the others, this dish had a greenish-blue mold growing in the center. At first glance, most people might have thrown it away as a ruined experiment. But Fleming, curious by nature, saw something different. He noticed that the bacteria surrounding the mold had stopped growing, as if repelled by an invisible force.

What makes this moment remarkable is that it was an accident, an unplanned, almost trivial oversight but Fleming’s sharp eye turned it into a discovery. He didn’t dismiss the dish as contaminated or spoiled. Instead, he carefully studied the mold, realizing it produced a substance that killed bacteria.

The Discovery of Penicillin

Fleming quickly identified the mold at first as a mold juice which he later calledPenicillium notatum. He found that this mold released a substance that could destroy harmful bacteria without harming human cells, a property that was revolutionary for the time. In the 1920s, even minor infections could turn deadly because there were no effective drugs to combat bacterial diseases. Doctors relied on antiseptics, which could clean wounds but often failed to stop infections inside the body. Fleming realized that penicillin could do what no other treatment could, target bacteria directly and safely.

According to Lifecyclebio Fleming later reflected on this moment, writing: “One sometimes finds what one is not looking for. When I woke up just after dawn on Sept. 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I guess that was exactly what I did.”

In his lab notes, He described how the substance killed bacteria such as those causing pneumonia, scarlet fever and strep infections. The discovery was exciting but the implications were enormous. For the first time, there was a chemical agent capable of controlling infections that had haunted humans for centuries. In a way, Fleming had unlocked a new form of medicine, one that treated illness at its root rather than just managing its symptoms.

However, He faced a significant challenge. Penicillin was extremely fragile, breaking down quickly when extracted from the mold. Producing it in large quantities seemed nearly impossible. For over a decade, penicillin remained mostly a laboratory curiosity. Fleming published his findings but the scientific community did not immediately recognize the potential. It would take years and the collaboration of teams of dedicated scientists during World War II to transform Fleming’s discovery into a drug that could save millions of lives.

A Race Against Time: World War II and Mass Production

The world didn’t fully grasp penicillin’s potential until the 1930s and 1940s, when infections continued to claim lives at alarming rates. World War II created an urgent need for effective treatments, as soldiers in Europe and the Pacific were dying from infected wounds. The United States and Britain realized that mass-producing penicillin could save countless lives but the challenge was enormous. Extracting enough penicillin from mold for widespread use was not easy. The substance degraded quickly and large-scale production seemed almost impossible.

In response, a team of scientists including Howard Florey, Ernst Boris Chain and Norman Heatley developed innovative methods to produce penicillin in large quantities. They experimented with different molds, optimized growth conditions, and even used deep-tank fermentation to scale up production. The race was on, and time was critical, By 1944, penicillin became available to treat Allied soldiers,reducing deaths from infected wounds and transforming the way medicine was practiced. What had started as a forgotten experiment in a messy London lab had become a lifeline for millions in wartime.

Penicillin’s mass production marked the beginning of the antibiotic era. Suddenly, diseases that had killed thousands or even millions became treatable. Hospitals across the world adopted penicillin as a front line defense against bacterial infections and researchers began searching for other substances with similar powers. Fleming’s accidental discovery had sparked a revolution in medicine, creating new possibilities for science, public health and the fight against infectious disease.

The Era of Antibiotics and Its Impact

Penicillin didn’t just save lives during the war, it changed the way humans approached illness forever. Before antibiotics, small infections could lead to amputations or death. Now, doctors could treat conditions like pneumonia, gonorrhea, and scarlet fever effectively. Penicillin inspired the search for new antibiotics, eventually leading to drugs like streptomycin, tetracycline and erythromycin, which broadened the fight against bacteria. The discovery also paved the way for modern medicine, where bacterial infections are rarely fatal in countries with access to these treatments.

The impact of penicillin extended beyond hospitals and clinics. It transformed society by reducing the fear of common infections, allowed for longer lifespans, and enabled advances in surgeries and childbirth, where infection had previously been a significant risk. Scientists also learned an important lesson: sometimes, accidents and mistakes lead to the most profound discoveries. Fleming’s curiosity and careful observation made the difference. Without noticing the mold in a forgotten Petri dish, the world might have waited decades longer for a drug that saves millions of lives every year.

Even today, the story of penicillin inspires scientists and students alike. It demonstrates the power of curiosity, observation, and persistence. Modern antibiotics may be more complex, but the principle remains the same, pay attention, explore the unexpected and be willing to follow where evidence leads. Fleming’s forgotten experiment reminds us that sometimes the path to discovery is not neat or planned, it’s messy, surprising and filled with unexpected possibilities.

Lessons from a Moldy Dish

Alexander Fleming’s story is not just about medicine,it’s about the way humans approach discovery. Many breakthroughs in history have been accidental, from X-rays to the microwave oven. What sets successful scientists apart is not just luck but the ability to recognize something unusual, investigate it and imagine its potential. Fleming’s Petri dish could have ended up in the trash but he saw opportunity in what others would have dismissed.

Penicillin also teaches a lesson about patience and collaboration. Fleming discovered it, but it took years for others to figure out how to make it practical. Science is rarely a solo endeavor. It builds on observations, experiments and innovations over time. Fleming’s discovery ignited a chain of efforts that eventually led to a global medical revolution, showing that even a small, accidental finding can have profound, long-lasting consequences.

Finally, penicillin reminds us that the world often rewards curiosity. Fleming’s attention to a single, overlooked Petri dish changed medicine forever. It’s a story that continues to inspire generations of scientists, doctors, and students, the next world-changing idea might be hiding in a corner of a messy lab, waiting for someone to notice it.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...