Your Body on Stress: What Cortisol Really Does

Stress is often portrayed as the enemy, a force we must eliminate to live fully. But at its core, stress is not an adversary. It is a biological signal, a messenger hormone called cortisol, designed to prepare our bodies for challenges, to sharpen focus and to help us survive. It is only when stress persists and the signals refuse to switch off, that it becomes a problem. Across Africa, people navigate complex urban and rural pressures, from congested cities to economic instability, from academic competition to climate uncertainties, they often carry invisible cortisol burdens that influence health, behaviour and wellbeing.

Understanding cortisol offers a lens into this daily negotiation between biology and environment. Yet when stress becomes chronic rather than fleeting, when cortisol levels stay elevated for days, weeks, or even months, the body and mind begins to pay a heavy price. So, what happens when the very system designed to protect us starts to wear us down?

The Body’s Alarm System

Cortisol works byregulating the body's stress response and metabolism, primarily by increasing blood sugar and energy availability, suppressing inflammation and influencing blood pressure. It is produced by the adrenal glands, small organs sitting atop the kidneys, as part of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This axis regulates the body’s response to stress, coordinating signals between the brain and the endocrine system. When a person perceives a threat, be it a physical danger or a looming deadline, cortisol levels rise, triggering a cascade of physiological responses. The heart rate increases, glucose is released into the bloodstream, immune function temporarily shifts and cognitive focus sharpens. This is the body preparing for action.

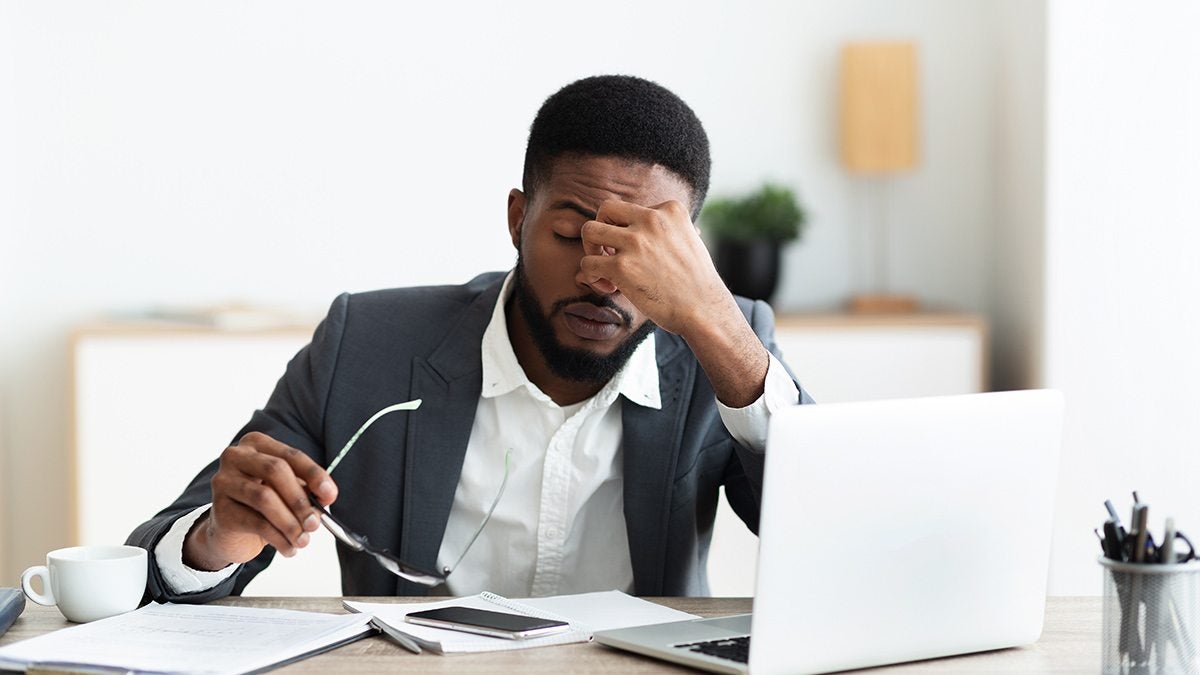

Now, cortisol can be both friend and foe. Its short-term surges allow survival, while long-term elevation undermines health. In African contexts, these surges are frequent. For a market trader, cortisol can spike when negotiating supply costs under volatile currency fluctuations. For a university student, it rises before high-stakes exams or during moments of social and academic pressure. For office workers, it pulses with the rhythm of urban traffic jams, infrastructure delays and looming project deadlines. In each case, the hormone is performing its intended function but the cumulative toll of repeated surges can be profound on one's overall health.

Chronic Stress and Its Consequences

Acute stress is adaptive. However, chronic stress is corrosive. When cortisol levels remain elevated for extended periods, the body begins to experience physiological strain. Elevated cortisol can disrupt metabolic regulation, leading to increased abdominal fat, insulin resistance and heightened cardiovascular risk. It can also impair cognitive function, weaken memory and interfere with sleep. The hippocampus, a brain structure crucial for memory formation, learning and spatial navigation, is particularly sensitive to prolonged cortisol exposure.

In our communities, chronic stressors abound. Factors such as unpredictable commuting times, financial insecurity, social inequality and environmental intervention all contribute to a persistent state of physiological alertness. Surveys have indicated that office workers and students often report symptoms consistent with sustained stress: chronic fatigue, headaches, sleep disturbances and emotional irritability. This goes to show that stress is not only psychological, it manifests biologically and socially, shaping daily experience across the continent.

Cortisol and Daily Functioning

Cortisol’s influence extends to performance as well. Its natural rhythm peaks in the morning, facilitating alertness and readiness for the day. This early-morning surge helps individuals rise, focus and engage with their environment. Short bursts of stress can sharpen memory, quicken responses and boost motivation. However, when stress lingers, it dulls mental flexibility, clouds judgment and increases fatigue. Tasks that require creative thinking, complex problem-solving or emotional regulation are specifically affected.

African workplaces, educational institutions, and households all reveal the effects of prolonged cortisol exposure. Teachers managing large classrooms may experience constant stress signals, students preparing for national exams face relentless pressure, and entrepreneurs in volatile markets navigate uncertainty daily. Chronic stress reshapes performance, and in environments with limited structural support such as mental health resources or stable infrastructure, the impact of cortisol is magnified.

Emotional and Psychological Dimensions

Cortisol interacts intimately with the brain’s limbic system, which governs emotion. Elevated levels are associated with anxiety, mood swings, irritability, and depressive symptoms. Persistent stress in African contexts is often compounded by economic pressures, social obligations and exposure to environmental instability. Unlike acute stressors, which come and go, these ongoing demands keep cortisol elevated and sometimes unnoticed, shaping mental wellbeing over time.

This is harmful because the body's stress response system, originally designed for short-term threats, stays constantly activated. The long-term activation disrupts nearly all bodily processes, significantly increasing the risk of serious physical and mental health conditions. This insight is particularly relevant across Africa, where the anticipation of uncertainty can drive chronic physiological stress without any immediate danger present.

Lifestyle, Diet, and Cortisol Regulation

Cortisol is responsive to lifestyle factors. Sleep quality, nutrition, exercise and social support all influence its regulation. Traditional African diets, often rich in fiber, legumes, grains and vegetables, help to provide nutrients that help modulate stress responses. So also, diets high in refined sugars, caffeine and processed foods can intensify cortisol spikes.

Physical activity is one of the most potent modulators though. Regular aerobic exercise reduces basal cortisol levels and improves resilience to stress. Mindfulness practices, meditation, and communal rituals, all of which are integral in many African societies, serve as culturally embedded methods for alleviating stress. Religious and spiritual practices also provide additional avenues for social support and cognitive reframing, helping regulate cortisol over time.

Adaptation and Resilience

When properly managed, stress is, in fact, not harmful. Cortisol prepares the body to face immediate challenges, and many African communities have long demonstrated resilience to environmental, social and economic stressors. The ability to adapt; through social networks, cultural practices, and daily routines, is as vital as the hormone itself. Short-term spikes in cortisol enhance alertness and focus, supporting survival in unpredictable environments.

Resilience, however, requires mechanisms to turn stress off. Chronic stress without recovery leads to a cumulative wear-and-tear on the body that can manifest in illness, mental health challenges and decreased longevity. Across the continent, balancing adaptation with recovery is essential, whether through rest, social support or structured interventions.

Managing Stress in Modern Africa

Understanding cortisol provides a roadmap for managing stress effectively. Africans navigating complex urban environments, economic uncertainty and social pressures can adopt strategies to modulate stress responses. Consistent sleep routines, regular exercise, balanced diets, and culturally relevant mindfulness practices help regulate cortisol. Community support networks, mentorship and social engagement further buffer against chronic stress.

The challenge lies not in eliminating stress but in designing daily environments and routines that allow cortisol to serve its intended purpose, which is alertness, energy mobilization, and adaptive response. By recognizing cortisol’s dual role, a friend in the short term, and a foe in the long term, individuals can engage with stress as a manageable biological signal rather than an uncontrollable enemy.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...