You may also like...

Yamal's Unstoppable Rise: Barcelona Star Shatters Records with Incredible Scoring Streak

)

Barcelona's teenage sensation Lamine Yamal continues to shatter records, surpassing football icons in goal-scoring and d...

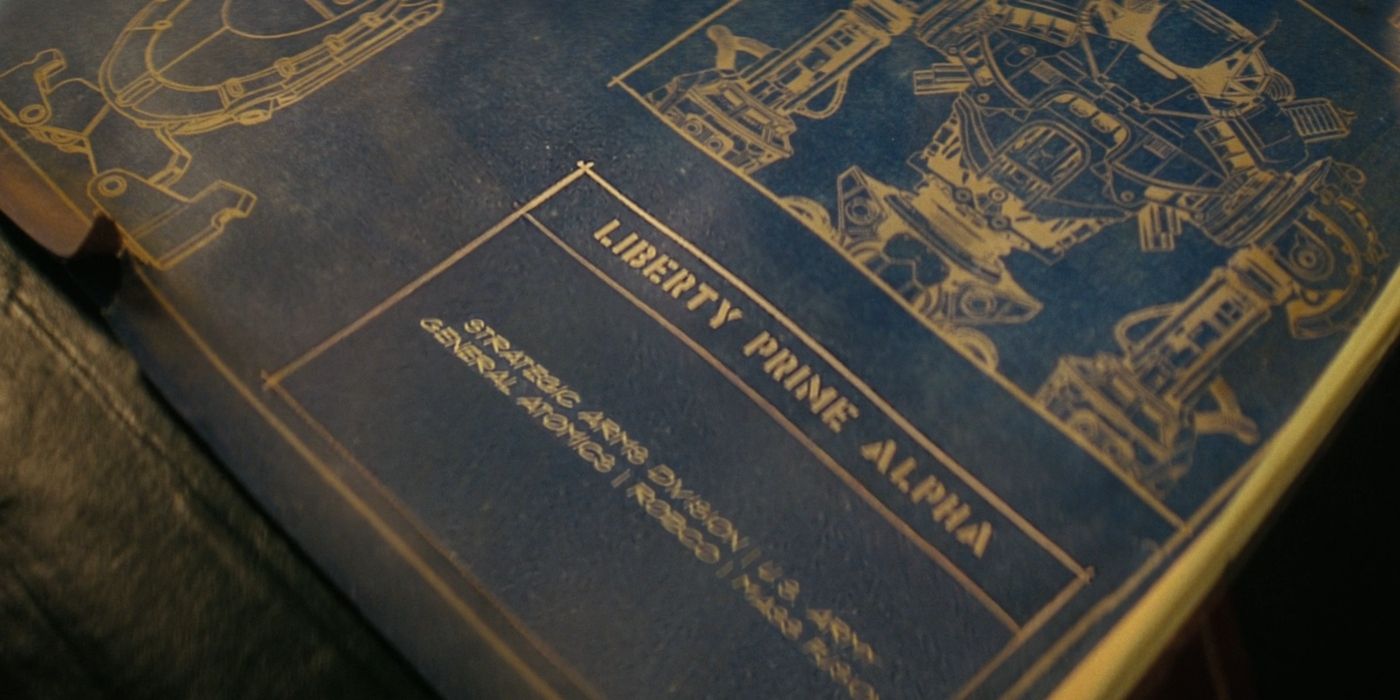

Fallout S2 Unveils Master Plan: Hidden Twists & Riskiest Game Setups Explored

The Fallout Season 2 finale unveils two pivotal plot points that will shape its future: Elder Cleric Quintus's declarati...

Hollywood Shakes: Paul Thomas Anderson Dominates DGA Awards, Kumail Nanjiani Stirs Controversy

Kumail Nanjiani hosted the 78th annual DGA Awards, delivering a sharp monologue that humorously critiqued Hollywood whil...

Bad Bunny Set to Electrify Super Bowl Halftime Stage!

Bad Bunny's Super Bowl Halftime Show is generating unprecedented controversy and debate, with discussions ranging from h...

Rock Icon Brad Arnold of 3 Doors Down Passes Away at 47 After Cancer Battle

Brad Arnold, the founding member and lead singer of 3 Doors Down, has passed away at 47 after battling stage 4 kidney ca...

Bone Broth Breakthrough: Uncover the Ultimate Timing for Collagen and Joint Benefits

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Health-GettyImages-1945415097-2afb2a5aefad4e23bfc40e04a062a3ca.jpg)

Bone broth offers a wealth of health benefits, including supporting joint health, aiding sleep, boosting energy, promoti...

Unlock the Secrets: Discover the Optimal Time for Bone Broth Benefits!

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Health-GettyImages-1945415097-2afb2a5aefad4e23bfc40e04a062a3ca.jpg)

A comprehensive guide explores the multifaceted benefits of bone broth, detailing how its consumption can be optimized f...

Nioh 3 Masterpiece: Perfecting the Art of Soulless Game Design

Nioh 3 is hailed as the best entry for fans of Koei Tecmo's challenging action RPG series, emphasizing intense combat an...