When the Desert Eats the City: Urban Expansion and Desertification in the Sahel

The Shifting Sands — A Creeping Crisis Moving Towards the Cities

Out in the Sahel, that narrow band of land between the Sahara and the more lush south of Africa, something insistent and quiet is creeping. Most individuals don't even realize it. Year after year, the desert edges closer to the cities. Niamey, Nouakchott, N’Djamena—they’re not falling to war or floods. It’s just sand, swallowing up neighborhoods, fields, roads. “When the desert eats the city”—that used to sound like a bad metaphor. Now, it’s just the truth.

People here have always lived on the edge. Rain shows up when it wants to, the soil is tired, and everyone hustles for water and land, hoping luck’s on their side. Recently, however, that fine equilibrium has broken. Climate change. Vanishing trees. More people than the land can handle. The desert keeps crawling south. Grasslands shrivel into cracked earth. Wells dry up the moment you fill a pail. Dust storms, which previously were unimaginable, now roar through numerous times a month, coloring the sky orange and layering everything with grit.

You’d expect the cities to be a safe haven. Not really. As drought pushes them off their land, urban centers such as Niamey swell. The city has expanded fourfold since the '80s. Bamako and Ouagadougou simply stretch themselves further and further, devouring what little is left of trees and grasses that formerly anchored the earth. New houses are constructed, but below them, the land washes away. No roots, no leaves—the ground dries out, and the desert closes in.

And here’s the kicker: running from the desert just makes it worse. Temporary camps chew up what little firewood and water remain. Farmland gets worked to exhaustion. City officials can’t keep up. Environmental plans get lost in the shuffle.

But it’s not all bleak. All across the Sahel, people—farmers, young folks, aid groups—are pushing back. They’re planting trees to slow the wind, reviving old water-saving tricks, building “green walls” to hold the desert back. The big question is if these efforts can outpace a stubborn climate and a population that won’t stop growing.

Human Stories from the Edge

For people living in these fast-growing cities, desertification isn’t some far-off worry. It’s in their faces every day. Up north in Nigeria, sand dunes are swallowing villages near Kano. In Niger’s capital, homes just buckle under the shifting sands. Every week, women have to walk even farther to find water, and food keeps getting pricier as farmland disappears.

A shopkeeper in Maradi shook his head and said, “The trees have vanished, and the wind feels like fire.” Over in Nouakchott, a teacher remembered when the city was lush with palms and gardens; now, he said, “the sand crawls into our homes.”

These changes don’t just hit the land — they hit people. More folks from rural areas end up squeezed into cities that are already struggling with poverty. That just ramps up the pressure over jobs and space. Young people can’t find work or farm, so they get stuck. Some drift toward radical groups or make the risky journey north to Libya, desperate to escape what feels like a dying homeland.

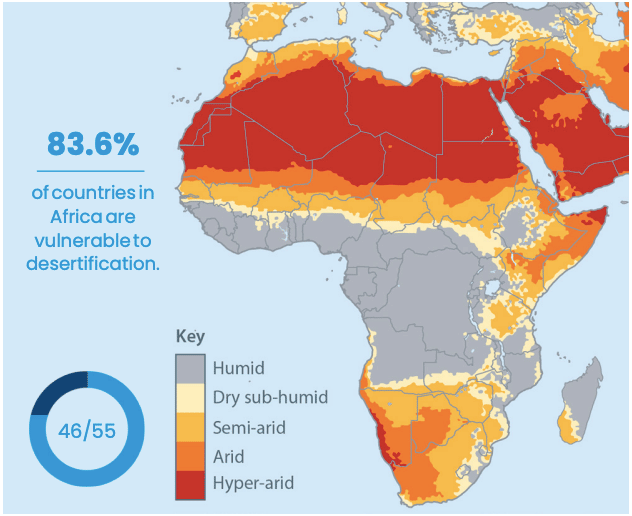

Governments aren’t blind to all this. The African Union kicked off the Great Green Wall Initiative — a huge plan to restore 100 million hectares of battered land across 11 countries, all the way from Senegal to Djibouti. It’s been a mixed bag so far, but there are bright spots. In Niger, farmers have managed to bring over five million hectares back to life by letting nature take the lead, giving people some hope and pushing back the desert. In Burkina Faso, old-school water-harvesting tricks like “zai pits” are turning dead soil green again.

But honestly, these wins are fragile. Urban planners keep sounding the alarm: if cities don’t get smart about green spaces, waste, and water, all those rural gains could vanish under a wave of city sprawl.

Climate scientist Fatima Bello said it best: “The Sahel’s battle is no longer just between people and nature — it’s between the city and its surroundings. One cannot survive without the other.”

Can the Sahel Take Back Its Future?

The fate of Sahel cities finally rests on how fast they can transition—and whether or not they are interested in using the environment as a starting point, instead of an aside. Some cities are doing just that. Dakar, for example, in Senegal, is introducing an urban greening strategy, with heat- and erosion-resistant trees and green bands to mitigate heat and erosion. In Mali, in turn, community leaders from Gao and Timbuktu are experimenting with sustainable homes made of heavy earth bricks. The houses stay cooler, are less expensive, and wither better to dust storms.

Technology’s getting in on the action, too. With satellites, governments can actually track the desert inching closer and spot the areas that need help the most. Young people are also getting in on the action, launching green businesses that teach neighbors how to install, recycle, and preserve. In Chad, there is an initiative known as Sahel Innovate that is instructing young people to create micro-forests using the Miyawaki method. The dense, little forests grow very fast and thrive in some of the harshest conditions.

But let's be realistic—climate change adaptation isn't all equal. For most in the Sahel, resilience is a luxury. It depends on your paycheck, what you know, and whether leaders are actually paying attention. Richer neighborhoods can afford tree planting and air filters. Poorer ones just get left out, wide open to the heat and dust. If nobody deals with these gaps, all this green progress just ends up deepening the divide.

Sahel's story isn’t neat or simple. It’s both a warning and a test run for the rest of us. You see how fast the climate crisis can blur the line between nature falling apart and society unraveling. But it also illustrates how resilient such communities are. Even when times are hard, people just keep finding ways to rebuild and move on.

If the desert is consuming the city, maybe it's time for the city to fight back—not just with concrete, but with creativity, cooperation, and genuine respect for the land. Because in the Sahel, it's not merely a matter of pushing back against the sands. It's about rediscovering how to coexist with them.

You may also like...

Ndidi's Besiktas Revelation: Why He Chose Turkey Over Man Utd Dreams

Super Eagles midfielder Wilfred Ndidi explained his decision to join Besiktas, citing the club's appealing project, stro...

Tom Hardy Returns! Venom Roars Back to the Big Screen in New Movie!

Two years after its last cinematic outing, Venom is set to return in an animated feature film from Sony Pictures Animati...

Marvel Shakes Up Spider-Verse with Nicolas Cage's Groundbreaking New Series!

Nicolas Cage is set to star as Ben Reilly in the upcoming live-action 'Spider-Noir' series on Prime Video, moving beyond...

Bad Bunny's 'DtMF' Dominates Hot 100 with Chart-Topping Power!

A recent 'Ask Billboard' mailbag delves into Hot 100 chart specifics, featuring Bad Bunny's "DtMF" and Ella Langley's "C...

Shakira Stuns Mexico City with Massive Free Concert Announcement!

Shakira is set to conclude her historic Mexican tour trek with a free concert at Mexico City's iconic Zócalo on March 1,...

Glen Powell Reveals His Unexpected Favorite Christopher Nolan Film

A24's dark comedy "How to Make a Killing" is hitting theaters, starring Glen Powell, Topher Grace, and Jessica Henwick. ...

Wizkid & Pharrell Set New Male Style Standard in Leather and Satin Showdown

Wizkid and Pharrell Williams have sparked widespread speculation with a new, cryptic Instagram post. While the possibili...

Victor Osimhen Unveils 'A Prayer From the Gutter', Inspiring Millions with His Journey

Nigerian football star Victor Osimhen shares his deeply personal journey from the poverty-stricken Olusosun landfill in ...