Vulvodynia is a complex and often debilitating condition. The International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) defines vulvodynia as vulvar pain lasting at least 3 months without an identifiable cause, although potential contributing factors may be present. Vulvodynia is considered an idiopathic pain disorder and remains a diagnosis of exclusion. Clitorodynia, a specific subtype of vulvodynia, refers to chronic pain localized to the clitoris and is similarly complex.

Symptoms of vulvodynia vary in intensity and location, often presenting as burning, irritation, or increased sensitivity. Clitorodynia, characterized by intense pain localized to the clitoris, is usually worsened by touch, pressure, sexual activity, or a feeling of rawness. These symptoms can significantly impact daily life, intimate relationships, and sexual pleasure. Although the exact causes of vulvodynia and clitorodynia remain unclear, research points to a multifactorial etiology involving nerve dysfunction, inflammation, and hormonal imbalances. A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach is crucial for timely diagnosis and effective management, thereby enhancing both physical and emotional well-being.

Etiology

The exact cause of vulvodynia remains unknown, with ongoing research focused on identifying potential contributing factors. These may include nerve injury or irritation affecting pain transmission from the vulva to the spinal cord, an increased number and sensitivity of vulvar nerve fibers, elevated levels of inflammatory substances such as cytokines, abnormal responses to environmental triggers, genetic predisposition, and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, including weakness, spasms, or instability.[1]

Vulvodynia can be classified as either generalized or localized, depending on the location of the pain. Symptoms may arise spontaneously or be triggered by touch or pressure. The condition is further categorized as primary, when present from the onset of symptoms in a patient’s life, or secondary, when it develops later, such as after exposure to a new partner. Additionally, the timing of symptoms may also vary, with pain described as intermittent, persistent, constant, immediate, or delayed in relation to specific activities.[2][3]

The exact cause of clitorodynia, or clitoral pain, remains unknown. The clitoris, rich in thousands of nerve endings and central to female sexual arousal, can cause significant distress and negatively impact quality of life when affected by pain.[2][3][4]

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of vulvodynia was reported as 3.1% in 2012 by Reed.[5] By 2014, the incidence had increased to 4.2 cases per 100 woman-years, with variation based on age, ethnicity, and marital status. An independent population-based study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) reported a point prevalence of 3% to 7% among reproductive-aged women.[6][7] Three of the studies included clinical confirmation. By age 40, approximately 7% of American women will experience symptoms consistent with vulvodynia. However, only 1.4% of women who seek medical care receive a correct diagnosis.[6] Although underdiagnosed, clitorodynia is significantly less common than vulvodynia, affecting fewer than 1% of women based on case reports.

Pathophysiology

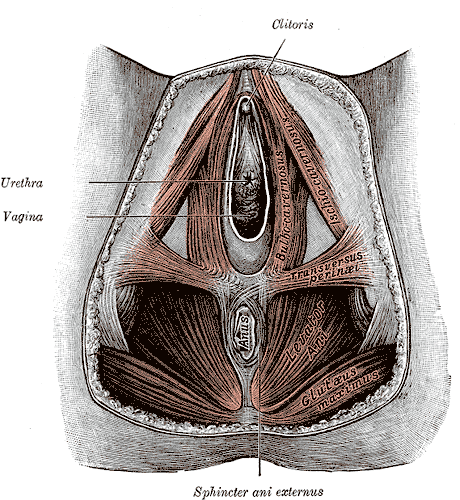

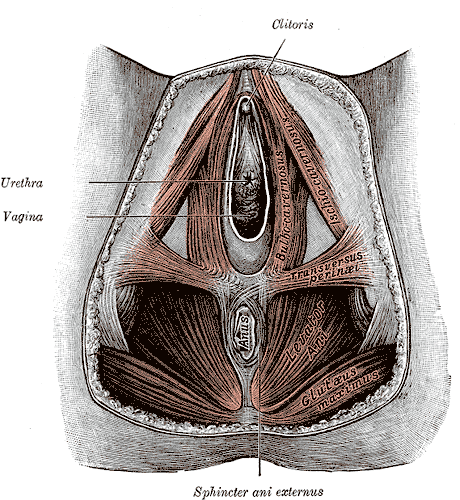

A comprehensive understanding of the vulva and vulvar vestibule anatomy is crucial for accurately diagnosing and managing vulvodynia. The vulva is the external female genitalia, and it includes the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoral hood, clitoris, and vestibule (see Anatomy of the Female Perineum).

The vulva is innervated by the anterior labial branches of the ilioinguinal nerve, the genitofemoral nerve, and branches of the pudendal nerve. Near the medial aspect of the ischial tuberosity, the pudendal nerve divides into the following 3 main branches:

The pudendal nerve also innervates the external anal sphincter and the deep muscles of the urogenital triangle.

The pelvic floor muscles are categorized into 3 categories, as mentioned below.

The internal pudendal artery, vein, and nerve travel through the Alcock canal, providing neurovascular support to the pelvic floor musculature.

History and Physical

A detailed medical history is essential for diagnosing vulvodynia and, more specifically, clitorodynia, as it aids in distinguishing these conditions from other causes of vulvar pain. Clinicians should ask about the onset, duration, and character of the pain—whether it is constant or intermittent and localized or generalized. Identifying potential triggers, such as sexual activity, prolonged sitting, or wearing tight clothing, can offer valuable insights into factors that may exacerbate symptoms.

A comprehensive medical history of a patient should also include information on previous treatments and their effectiveness, as well as any underlying conditions, such as infections, hormonal imbalances, or pelvic floor dysfunction. Psychological factors, including anxiety, depression, and stress, should be assessed as they can contribute to or exacerbate symptoms. Additionally, reviewing medications and allergies is essential. Gathering this information helps establish a more accurate diagnosis and guides the development of an appropriate treatment plan.

The patient should undergo a thorough gynecological examination. After ruling out and addressing all potential infectious, inflammatory, hormonal, neoplastic, and neurological causes, a careful visual inspection of the vulva and vulvar vestibule should be performed.[1]

Evaluation

No specific laboratory tests exist for vulvodynia, as it remains a diagnosis of exclusion. When vulvodynia is suspected, additional diagnostic procedures, such as cultures or biopsies, may be performed to rule out infections, dermatological disorders, or neoplastic changes. These tests help ensure that underlying conditions do not cause symptoms and support the diagnosis of vulvodynia as a pain disorder of exclusion.

Treatment / Management

Managing vulvodynia requires a multidisciplinary approach. Validating the patient’s pain is essential, as many women endure symptoms in silence for extended periods or consult multiple practitioners without effective relief.[9] Care often involves an interprofessional healthcare team, which may include a gynecologist specializing in vulvovaginal health—often affiliated with organizations such as the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) and the ISSVD—as well as a dermatologist, neurologist, pain management specialist, urologist, and a physical therapist with expertise in women’s health.[10][11][12] (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

A thorough differential diagnosis of vulvodynia and clitorodynia is essential to rule out other conditions that may cause similar vulvar pain. Careful evaluation of clinical features, patient history, and diagnostic tests is critical to distinguishing these pain syndromes from infections, dermatological disorders, and other gynecological or urological conditions.

- Infectious causes: Vulvovaginal candidiasis (including atypical forms), bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes.

- Inflammatory conditions: Lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, contact dermatitis, and lichen simplex chronicus.

- Neoplastic disorders: Squamous cell carcinoma.

- Neurological disorders: Injury, entrapment, or neuropathy of the pudendal, genitofemoral, or ilioinguinal nerves, as well as Tarlov cysts. In cases of clitorodynia, the differential diagnosis should include irritation, compression, or damage to the pudendal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris.

- Trauma-related causes: Straddle injuries, female genital cutting, and motor vehicle accidents.

- Hormonal deficiencies: Estrogen deficiency.

- Nonspecific symptoms: Vaginal burning and irritation.

- Iatrogenic causes: Vulvar or vaginal pain.[12]

- Pelvic floor dysfunction: Muscle tension, weakness, or spasms, particularly relevant for clitorodynia.

- Medications: Certain drugs may cause pain.

- Keratin pearls or clitoral hood adhesions: Accumulation of keratin between the clitoris and the clitoral hood can lead to irritation and pain.[17][18]

Prognosis

The prognosis of vulvodynia and clitorodynia varies—some individuals experience symptom relief over time, while others may struggle with persistent pain. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary treatment approach can significantly improve outcomes. Although there is no universal cure, many patients achieve effective symptom management through a combination of medical, physical, and psychological therapies. Addressing contributing factors such as nerve dysfunction or musculoskeletal issues can lead to long-term relief.

Emotional and social support also have a vital role in enhancing an individual's quality of life. With appropriate care, many individuals report reduced pain intensity and improved daily functioning. Early symptom recognition is crucial for facilitating timely intervention, including access to pelvic floor therapy and emotional support. Even if complete remission is not achieved, ongoing emotional support can help patients manage their chronic condition and cope with intermittent flare-ups more effectively.

Complications

Vulvodynia, including clitorodynia, can result in significant physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. Chronic pain may interfere with daily activities, physical exercise, and sexual function, often leading to distress and strained intimate relationships. Many patients experience anxiety, depression, and a reduced quality of life due to persistent discomfort and the frustration of delayed diagnosis. Without appropriate management, vulvodynia may contribute to pelvic floor dysfunction, which can further intensify pain. Social withdrawal and feelings of hopelessness are also common, highlighting the importance of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to care. Early intervention and patient education are crucial in preventing long-term complications and promoting overall well-being.

Consultations

Managing vulvodynia often requires referrals to specialists such as gynecologists, pain management physicians, dermatologists, and pelvic floor physical therapists, depending on the complexity of the case. Interdisciplinary collaboration is critical to ensuring a comprehensive approach that addresses both the physical and psychological aspects of the condition. Mental health professionals, such as psychologists or counselors, may be involved to help patients cope with the emotional burden of chronic pain, while physical therapists provide support for pelvic floor rehabilitation. Timely referrals to the appropriate specialists can enhance diagnostic accuracy, optimize treatment strategies, and improve overall patient outcomes.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Education and awareness are vital for promoting early diagnosis and effective management of vulvodynia and clitorodynia. Clinicians should be trained to recognize these conditions as diagnoses of exclusion and appreciate their multifactorial nature. Educating patients about potential triggers, lifestyle modifications, and treatment options empowers them to take an active role in managing their symptoms. Open communication between healthcare providers and patients helps reduce stigma and facilitates timely intervention. Additionally, public health campaigns and professional education programs can raise broader awareness, ultimately enhancing patient quality of life and decreasing the burden of undiagnosed or mismanaged cases.

Pearls and Other Issues

Research on vulvodynia is ongoing, with chronic pain affecting approximately 25% of adult Americans. Unfortunately, patients experiencing chronic pain often face neglect and undertreatment. Vulvodynia and clitorodynia can be severe and debilitating, yet scientific evidence supporting treatment options remains limited, with few randomized controlled trials available. Although treatment outcomes vary, most women experience improvement with appropriate care. Clinicians should take patients’ concerns seriously and acknowledge these conditions as legitimate. Practitioners who are uncertain about treatment or lack sufficient education and experience should refer patients to the National Vulvodynia Association for guidance in finding qualified healthcare professionals.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The cause of vulvodynia, and specifically clitorodynia, remains unknown, making treatment challenging. Effective management requires an interprofessional approach that prioritizes the patient’s reported pain and its severity. Many women endure symptoms in silence or consult multiple clinicians without achieving pain relief. Care for these patients often involves a team of specialists, which may include a gynecologist with expertise in vulvovaginal health (often affiliated with organizations such as ISSWSH and ISSVD), a dermatologist, a nurse practitioner, a neurologist, a pain management specialist, a urologist, and a physical therapist specializing in women’s health.[10]

Effective treatment strategies must be individualized to each patient’s needs. Unfortunately, even with a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach, some individuals may continue to experience persistent or recurrent pain that profoundly affects their daily lives and interpersonal relationships. Ongoing research is critical to advancing the understanding and treatment of vulvodynia and clitorodynia. Continued investigation into underlying pathophysiology, potential biomarkers, and innovative therapies will support the development of more targeted, evidence-based interventions aimed at improving patient outcomes and overall quality of life.[16][19]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Anatomy of the Female Perineum. The female perineum comprises key anatomical structures, including the clitoris, urethra, vagina, sphincter ani externus, anus, gluteus maximus, levator ani, and transversus perinei.

References

[1]

Vieira-Baptista P, Lima-Silva J, Pérez-López FR, Preti M, Bornstein J. Vulvodynia: A disease commonly hidden in plain sight. Case reports in women's health. 2018 Oct:20():e00079. doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2018.e00079. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30245974]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[2]

Dias-Amaral A, Marques-Pinto A. Female Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder: Review of the Related Factors and Overall Approach. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2018 Dec:40(12):787-793. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675805. Epub 2018 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 30428492]

[3]

Schlaeger JM, Glayzer JE, Villegas-Downs M, Li H, Glayzer EJ, He Y, Takayama M, Yajima H, Takakura N, Kobak WH, McFarlin BL. Evaluation and Treatment of Vulvodynia: State of the Science. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2023 Jan:68(1):9-34. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13456. Epub 2022 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 36533637]

[4]

Coady D, Kennedy V. Sexual Health in Women Affected by Cancer: Focus on Sexual Pain. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Oct:128(4):775-91. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001621. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27607852]

[6]

Reed BD, Haefner HK, Harlow SD, Gorenflo DW, Sen A. Reliability and validity of self-reported symptoms for predicting vulvodynia. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2006 Oct:108(4):906-13 [PubMed PMID: 17012453]

[7]

Torres-Cueco R, Nohales-Alfonso F. Vulvodynia-It Is Time to Accept a New Understanding from a Neurobiological Perspective. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021 Jun 21:18(12):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126639. Epub 2021 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 34205495]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, Feranec J. Evaluation and Treatment of Female Sexual Pain: A Clinical Review. Cureus. 2018 Mar 27:10(3):e2379. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2379. Epub 2018 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 29805948]

[9]

Webber V, Bajzak K, Gustafson DL. Regarding Webber, V., Bajzak, K. and Gustafson, D. L. (2023). The impact of rurality on vulvodynia diagnosis and management: Primary care provider and patient perspectives. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine, 28 (3), 107-115. Canadian journal of rural medicine : the official journal of the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada = Journal canadien de la medecine rurale : le journal officiel de la Societe de medecine rurale du Canada. 2025 Jan 1:30(1):48-49. doi: 10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_62_24. Epub 2025 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 40052781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[10]

Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, Bergeron S, Pukall C, Zolnoun D, Coady D, consensus vulvar pain terminology committee of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH), International Pelvic Pain Society (IPPS). 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH, and IPPS Consensus Terminology and Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain and Vulvodynia. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016 Apr:13(4):607-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.167. Epub 2016 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 27045260]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[11]

Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, Bergeron S, Stein A, Kellogg-Spadt S. Vulvodynia: Assessment and Treatment. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016 Apr:13(4):572-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.020. Epub 2016 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 27045258]

[12]

Vasileva P, Strashilov SA, Yordanov AD. Aetiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of vulvodynia. Przeglad menopauzalny = Menopause review. 2020 Mar:19(1):44-48. doi: 10.5114/pm.2020.95337. Epub 2020 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 32699543]

[13]

Newman DK, Lowder JL, Meister M, Low LK, Fitzgerald CM, Fok CS, Geynisman-Tan J, Lukacz ES, Markland A, Putnam S, Rudser K, Smith AL, Miller JM, Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium. Comprehensive pelvic muscle assessment: Developing and testing a dual e-Learning and simulation-based training program. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2023 Jun:42(5):1036-1054. doi: 10.1002/nau.25125. Epub 2023 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 36626146]

[14]

Falsetta ML, Foster DC, Bonham AD, Phipps RP. A review of the available clinical therapies for vulvodynia management and new data implicating proinflammatory mediators in pain elicitation. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2017 Jan:124(2):210-218. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14157. Epub 2016 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 27312009]

[15]

Loflin BJ, Westmoreland K, Williams NT. Vulvodynia: A Review of the Literature. The Journal of pharmacy technology : jPT : official publication of the Association of Pharmacy Technicians. 2019 Feb:35(1):11-24. doi: 10.1177/8755122518793256. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 34861006]

[16]

Queiroz JF, Sarmento ACA, Aquino ACQ, de Souza ATB, de Medeiros KS, Falsetta ML, Gonçalves AK. Psychotherapy and Psychotherapeutic Techniques for the Treatment of Vulvodynia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2025 Feb 24:():. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000881. Epub 2025 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 39993259]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[17]

Romanello JP, Myers MC, Nico E, Rubin RS. Clitoral adhesions: a review of the literature. Sexual medicine reviews. 2023 Jun 27:11(3):196-201. doi: 10.1093/sxmrev/qead004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36973166]

[18]

Krapf JM, Kopits I, Holloway J, Lorenzini S, Mautz T, Goldstein AT. Efficacy of in-office lysis of clitoral adhesions with excision of keratin pearls on clitoral pain and sexual function: a pre-post interventional study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2024 Apr 30:21(5):443-451. doi: 10.1093/jsxmed/qdae034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38515327]

[19]

Rosen NO, Dawson SJ, Brooks M, Kellogg-Spadt S. Treatment of Vulvodynia: Pharmacological and Non-Pharmacological Approaches. Drugs. 2019 Apr:79(5):483-493. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01085-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30847806]

(3).jpeg)