BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 523 (2025) Cite this article

This study aimed to examine the factors that affect treatment delay in early childhood caries (ECC), guided by a modern medical model. This study attempted to analyze the pathways influenced by these factors and provide a theoretical foundation for designing targeted intervention programs.

Data were collected from young children who visited the department of stomatology at a tertiary hospital from January to December 2023. Data were collected via a general information survey questionnaire, the Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old Children (SOHO-5), the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale-Chinese (CFSS-DS-C), the Parental Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire-8 (P-CPQ-8), the Family Impact Scale (FIS-8), and the Perceived Barriers to Health Care-Seeking Decision-Chinese (PBHSD-C). The data in this study were analyzed using a variety of statistical tests, including the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests, correlation analysis, multiple stepwise regression analysis, and structural equation modeling (SEM).

The treatment delay score of early childhood caries was 36.77 ± 10.11, indicating that the state of early childhood caries was currently at a moderate level of delay. The SOHO-5 score was 6.41 ± 1.78, the CFSS-DS-C score was 23.60 ± 6.91, the P-CPQ-8 score was 18.43 ± 4.33, and the FIS-8 score was 18.66 ± 4.28. Multi-factor analysis revealed key factors affecting treatment delay, including permanent residence, medical insurance type, oral health habits, reasons for visit, first symptoms, the time of first discovery of oral problems, brushing teeth before bedtime every day, a genetic history of dental caries and the staging of dental caries. A positive correlation existed between oral health, children’s dental fear and treatment delay, whereas social support was negatively correlated with treatment delay. The SEM, which is based on the modern medical model, revealed that children’s dental fear plays a mediating role in the relationships among social support, oral health, and treatment delay.

The present study developed a novel model to study the ECC treatment delay, elucidated the causal links between the identified variables, and proposed potential intervention strategies to enhance oral health awareness, knowledge, and skills among young children and their parents. These strategies can help improve children’s dental visiting behavior and reduce treatment delay.

Although dental caries is essentially a preventable chronic health issue, recent global reports indicate that oral health has not significantly improved over the past 25 years [1]. Early childhood caries (ECC) is defined as the presence of one or more decayed, missing or filled teeth in children under the age of 6 [2]. Caries in children progress rapidly, often affecting multiple primary teeth and multiple tooth surfaces, which leads to a decline in chewing ability and can rapidly develop into deep decay and abscesses [3]. Severe early childhood caries (SECC) can even result in swelling, pain, and infection in the maxillofacial region, as well as various complications, such as abnormal development of the permanent tooth germ and maxillofacial structures [4, 5]. This condition not only severely impacts children’s oral health-related quality of life but also increases economic and social burdens [6]. The global random effects pooled prevalence of ECC was 48% (95% CI: 0.43–0.53). The random effects pooled prevalence varied by region: 30% (95% CI: 0.19–0.45) (Africa), 48% (95% CI: 0.42–0.54) (Americas), 52% (95% CI: 0.43–0.61) (Asia), 43% (95% CI: 0.24–0.66) (Europe) and 82% (95% CI: 0.73–0.89) (Oceania). Differences across countries account for 21.2% of the observed variance [7]. A systematic review of reports from 67 countries suggests that prevalence varies from 1 to 12% in most developed countries, but is estimated to be as high as 70% in underdeveloped and disadvantaged countries [8], with a disproportionate impact on disadvantaged populations [9]. Evidence from around the world shows that ECC is still relatively common, but rarely addressed [10]. The results of the fourth national oral health epidemiological survey in China indicated that the prevalence of dental caries among 5-year-old children was 71.9%, a significant increase from the 66.0% reported in the third epidemiological survey [11]. These findings suggest that untreated dental caries are highly prevalent. Despite the importance of addressing childhood caries, awareness, treatment, and control rates remain relatively low, resulting in common delays in patient care [12]. Additionally, young children represent a unique demographic, as their physical and mental development is still maturing, and their limited cognitive abilities hinder their capacity to assess their own health status. This often leads to delays in parental response to their children’s dental issues. Enhancing parents’ understanding of dental caries is crucial, as it can facilitate early dental intervention, improve compliance with medical recommendations, and alleviate the pain experienced by children [5]. Some socio-economic, behavioral and clinical variables were identified as risk factors for ECC [13]. Factors include: Age [14], socio-economic status [15], brushing frequency and supervised brushing frequency [16], fluoride exposure [17], breastfeeding and bottle feeding [18], dietary habits [19], dental attendance behaviors [20], previous caries experience [21] and microbiome [22].

The concept of treatment delay, which was first proposed by Pack and Gallo in 1938, was defined as the period from the first discovery of symptoms by a patient to their first visit to a medical institution, and a delay of 3 months or more was used as the standard for defining delay [23]. Owing to dental fear, children are usually unable to cooperate with conventional dental treatment, which involves injection with anesthetic, drilling, and extraction. Although dental treatment can be completed by strapping children with papoose boards or sedation, multiple mandatory constraints can easily lead to great psychological trauma to children, reduce parents’ self-efficacy, leave psychological shadows, and be detrimental to the development of physical and mental health [24]. Finally, parents often delay dental treatment due to their children’s fear, resulting in treatment delay. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the medical behavior of young children with caries.

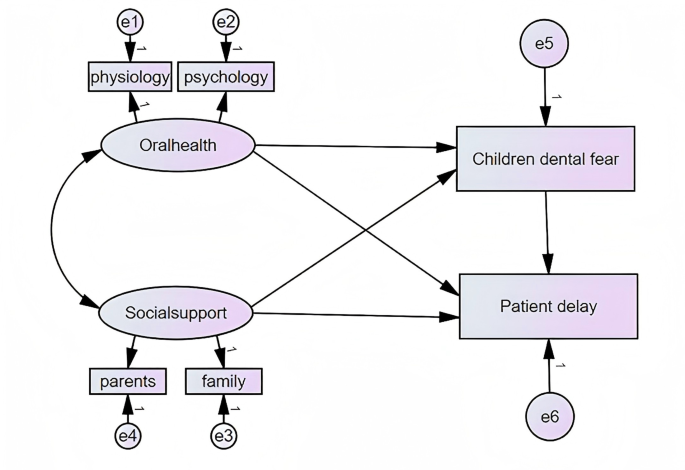

The modern medical model is a bio-psycho-social medical model. In 1978, the World Health Organization issued the Almaty Declaration at the International Conference on Primary Health Care, stating that “Health is a good state of physical, psychological and social adaptation, not simply the absence of disease or weakness” [25]. In this study, biology refers to children’s physical perception of the disease, psychology refers to children’s dental fear, and sociology refers to the care and education of families and healthcare professionals. All factors work together and influence each other, determining whether treatment delays behavior [26]. On the basis of the relationships among biology, psychology, and sociology in the modern medical model, this study constructed structural equation modeling (SEM) of oral health, children’s dental fear, social support and treatment delay. SEM serves as a pivotal tool for scrutinizing the relationships between observable (manifest) variables and underlying (latent) variables. Existing studies on treatment delay are usually limited to specific diseases, such as lung cancer or breast cancer, and few studies on ECC exist [27]. Given the high caries rate of children in China, effectively reducing the incidence of treatment delay is crucial. Understanding the influencing factors of delayed medical treatment in children is important for the formulation of appropriate intervention measures.

Based on the theoretical framework established within the modern bio-psycho-social medical model, it is hypothesized that good oral health is associated with reduced treatment delay in seeking dental care. An increased level of dental fear in children is positively correlated with treatment delay in receiving dental treatment. Social support acts as a moderator in the relationship between children’s dental fear and treatment delay. The overarching aim of the hypotheses is to elucidate the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and sociological factors that influence treatment delay in children with dental caries.

This was a cross-sectional study. The participants were patients and their parents who visited the hospital where the authors worked. Data were collected from January to December 2023. Participants were those attending the outpatient department and they were aged 3–6 years. The diagnosis of ECC was confirmed by clinical examination, which revealed one or more decayed, missing, or filled teeth. Children and their parents volunteered to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included children who revisited, children with other systemic or genetic diseases, and children with mental illness.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) combined with modern medical model was used to analyze the pathways of each variable. The SEM analysis necessitates a substantial sample size [28]. The sample size for influencing factors should adhere to the guidelines of the Kendall multivariate analysis, which stipulates that it should be at least 5–10 times the number of variables [29]. A total of 19 variables were included in this study. The sample size was 10 times the number of variables, and the loss rate was 20%. The calculated minimum sample size is 238 cases. To ensure the reliability of the results, a total of 280 questionnaires were collected, and 12 invalid questionnaires were excluded, resulting in an effective response rate of 95.7% and 268 children with caries were recruited finally.

According to the Helsinki Declaration of principles for human medical research (1964), the study participants were provided with oral information on the study design, objectives and their right to withdraw from the project at any time and for any reason. The study included parents/legal guardians who provided informed and voluntary consent. The ethical approval were obtained from the ethics committee of the 960th Hospital of the joint logistics support force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (approval No. JZMULL2023154).

The study employed a comprehensive set of research tools, including the Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old Children (SOHO-5), the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale-Chinese (CFSS-DS-C), the Parental Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire-8 (P-CPQ-8), the Family Impact Scale (FIS-8), and the Perceived Barriers to Health Care-Seeking Decision-Chinese (PBHSD-C). Participation is voluntary and the response is anonymous (serial number instead of name). The children who met the inclusion criteria were given oral examination. The physician checked the questionnaire results and eliminated invalid questionnaires with inconsistencies and regularity. To prevent data input errors, the data were collated, numbered and entered uniformly via the two-person input method, and the input data were reviewed to ensure data accuracy.

General information survey questionnaire

The general information survey questionnaire collected various factors, such as child age, sex, parental age, education level, income status, medical insurance type, permanent residence, oral health habits, reasons for medical treatment, first symptoms, the time of first discovery of oral problems, brushing teeth before bedtime every day, genetic history of dental caries, and staging of dental caries.

Scale of oral Health outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5)

SOHO-5 was developed by Tsakos et al. [30]. This is the first study to develop and validate a self-reported oral health-related quality of life measure for 5-year-old children. The quality of the cross-cultural adaptations and psychometric properties of SOHO-5 had been assessed. Almost all of the studies reported internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.71 to 0.90), test-retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient 0.46–0.98), and construct validity [31]. Tsakos uses 7 questions with 3 possible responses—No (0 points), A little (1 point), and A lot (2 points)—and scores ranging from 0 to 14. The higher the score is, the poorer the oral health status. The SOHO-5 score was used to represent children’s oral health status for correlation analysis.

Children’s fear survey schedule-dental subscale (CFSS-DS)

The CFSS-DS was developed by Melamed BG [32]. An improved Chinese version of the CFSS-DS was developed by Jia-Xuan LU [33]. The original English version of the CFSS-DS was translated into Chinese, pre-tested and cross-culturally adapted. The Cronbach’s alpha of the translated scale was 0.85 and test-rest reliability was 0.73. The 15 items were divided into four domains. There was some logical relationship between the items within the same domains. The Chinese version of the modified CFSS-DS has been established successfully with good psychometric properties, providing the theoretical basis for further application in the Chinese population [33]. Each item of the scale represents 5 options through facial expression pictures, namely, very afraid, quite afraid, relatively afraid, a little afraid, and not afraid at all. The score ranged from 1 to 5. The scale ranged from 15 to 75 points. The higher the score is, the greater the level of dental anxiety. The CFSS-DS score represents the degree of dental fear experienced by children for correlation analysis.

Parental caregiver perceptions questionnaire-8 (P-CPQ-8) and family impact scale (FIS-8)

The Child Oral Health-related Quality of Life (COHQoL) scale was developed by Jokovic A [34]. The Parental-Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ) and the Family Impact Scale (FIS) are part of the Child Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life (COHQoL) suite of instruments developed over a decade ago. The Chinese version was developed with minor modifications [35]. William M Thomson simplified short-form parental-caregiver perceptions questionnaire-8 (P-CPQ-8) and the Family Impact Scale-8 (FIS-8) [36]. The Cronbach’s α values for the P-CPQ-8 and FIS-8 were 0.8 and 0.83, respectively, indicating high reliability as these values fall within the acceptable range of 0.70 to 0.98 for exploratory research. The P-CPQ-8 and the FIS-8 seem to be well suited for health services research with high caries-experience samples. Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and appropriateness of the P-CPQ and the FIS in assessing the oral health-related quality of life among children receiving dental treatment under general anesthesia [36]. These two scales have a total of 16 items with scores ranging from 16 to 80. The higher the score is, the lighter the psychological impact. The items “whether feeling upset” and “whether feeling irritated or depressed” on the P-CPQ-8 were similar to those on the FIS-8, so they were combined into one item for this investigation. Since the items “difficulty chewing hard food” and “not wanting to talk to other children” were duplicated in SOHO-5, they were excluded from this study. In this study, the P-CPQ-8 and FIS-8 were used as two dimensions of parental support and family support in social support.

Perceived barriers to health care-seeking decision-Chinese (PBHSD-C)

PBHSD was developed by Al-Hassan et al. [37]. Li PW et al. developed the Chinese version of the Perceived Barriers to Health Care-seeking Decision (PBHSD-C) and evaluate its psychometric properties in Chinese patients with acute coronary syndromes [38]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale was 0.74, and the intragroup correlation coefficients of all the items were above 0.80, indicating strong item-to-item reliability. The scale for a single dimension consisted of 10 items. The scale scores ranged from 6 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater perceived barriers to health care-seeking decisions. The convergent validity of the PBHSD-C was also supported. The PBHSD-C is reliable and valid for assessing the extent of perceived barriers in the care-seeking of Chinese patients with ECC. PBHSD-C scores represented treatment delay for correlation analysis.

All the data were input, checked, rechecked and reviewed by the principal investigators according to standard procedures, and analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (statistical program for Social Sciences). The research results and statistical analysis are presented in the form of text and tables. Measurement data are presented as the means and standard deviations, whereas count data are presented as frequencies and composition ratios. The Kruskal‒Wallis and Mann‒Whitney tests were used to identify the impact of different types of general information on delayed medical treatment behavior. Multiple linear regression was used to analyze key factors affecting delayed medical treatment behavior, and Spearman correlation coefficients were used to analyze the correlations between variables. The SEM was constructed via Amos 24.0 software, and parameter estimation was performed via the maximum likelihood method. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study included a total of 268 valid questionnaires, with 87.69% of parents aged between 30 and 40. Among the participants, 86.2% of parents had a bachelor’s degree or above, and 27 had received a high school education or below. Other general data are shown in Table 1.

Scores for each scale from 268 children with ECC were analyzed. Descriptive statistics revealed that the treatment delay score was 36.77 ± 10.11, the SOHO-5 score was 6.41 ± 1.78, the CFSS-DS-C score was 23.60 ± 6.91, the P-CPQ-8 score was 18.43 ± 4.33, and the FIS-8 score was 18.66 ± 4.28 (Table 2).

Statistically significant general information variables were used in a multiple stepwise linear regression analysis to explore key factors influencing treatment delay. Poor oral health habits and compromised oral health status were identified as key factors influencing the delay. Social support plays a crucial role in mitigating the negative effects of ECC treatment delay. Dental fear can hinder access to dental care and exacerbate oral health problems. The multi-factor analysis results revealed that permanent residence, medical insurance type, oral health habits, reasons for visiting, first symptoms, the time of first discovery of oral problems, brushing teeth before bedtime every day, genetic history of dental caries and staging of dental caries significantly influenced treatment delay (p < 0.05), explaining 57.2% of the variation (R2 = 57.2%). The results are shown in Table 3. It is noteworthy that the delay rate of patients living in cities is lower than that of patients living in rural areas. Access to dental care services is generally more limited in rural areas than in urban areas, making it more difficult for their families to seek timely care. Rural children may have a higher intake of sugary foods and drinks, as well as poorer oral hygiene habits, due to factors such as limited access to dental health education and resources. The delay rate of patients receiving free medical care was lower than that of those receiving self-funding. Patients with a genetic history of dental caries had a lower delay rate than did those without a genetic history. Patients with dental fear had a higher delay rate than did those without. Dental fear may be exacerbated by painful experiences associated with dental treatments. This fear can lead to avoidance behaviors that further compromise oral health. In addition, the higher the level of social support that patients received, the lower the delay rate. Family and community resources can provide emotional and practical support to help children and their families cope with the challenges of ECC. Social support may include encouragement to seek dental treatment, help with transportation to dental appointments, or providing financial assistance for dental care.

A positive correlation existed between oral health, children’s dental fear and treatment delay, whereas social support was negatively correlated with treatment delay. The higher the score is, the poorer the oral health status. In addition, the higher the score is, the greater the perceived barrier to seeking healthcare decisions. The correlations between variables are presented in Table 4.

Initial model assumption

In the modern medical model, biological, psychological and social factors have direct impacts on health-seeking behavior. In addition, biological and social factors can influence health-seeking behavior through dental fear. Therefore, oral health and social support can be assumed to directly affect treatment delay, and both can influence treatment delay through dental fear. In the hypothesis model, social support and oral health served as independent variables, child dental fear served as a mediating variable, and treatment delay served as a dependent variable. As shown in Fig. 1, social support includes two dimensions: physical and psychological. Therefore, the latent variables of children’s dental fear and treatment delay with respect to the observed variables were replaced.

Model fitting

To confirm the model’s validity, researchers have evaluated the degree of model fit. Table 5 displays the results, which demonstrate a satisfactory fit. All path coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the effects of oral health, social support, and children’s dental fear on treatment delay were 0.63, -0.27, and 0.22, respectively. The final model is illustrated in Fig. 2. In the SEM, the indirect effect of children’s dental fear on oral health and treatment delay was 0.013, whereas the indirect effect on social support and treatment delay was 0.003. At the 90% confidence level, the population RMSEA for the default model is between 0.000 and 0.075. The 95% confidence intervals for the direct and indirect effects, as determined by the bootstrap method, were [0.295, 1.048] and [-0.302, 0.014], respectively. Therefore, children’s dental fear plays a partial mediating role between oral health and medical treatment delay, as well as between social support and medical treatment delay, and has an indirect effect on disease perception and medical treatment behavior.

The study revealed a moderate level of treatment delay for ECC among young children, with an average score of 36.77 ± 10.11, indicating a significant delay in the treatment of ECC among young children. The results indicated that social support plays a crucial role in reducing treatment delay, with a negative correlation of -0.472 (p < 0.01) between social support and treatment delay. This implies that children with greater social support tend to seek treatment more promptly. Oral health status, as measured by the SOHO-5 scale, was also found to have a significant impact on treatment delay, with an effect size of 0.63. This suggests that better oral health is associated with less delay in seeking treatment. In addition, dental fear was identified as a factor directly influencing treatment delay, with a direct effect of 0.22. This indicates that reducing dental fear in young children could lead to a decrease in treatment delay behavior.

Although the reasons for the occurrence of dental caries in children have been the focus of research, little research has been conducted on their medical behavior. Children’s anxiety regarding dental treatment frequently leads to avoidance of medical treatment, resulting in stress for both children and their parents. Understanding the factors influencing medical behavior is helpful for slowing the development of caries and reducing the incidence of caries in young children. The moderate treatment delay score for early childhood caries may be related to the fact that the oral health survey was conducted in the hospital; otherwise, the delay level could be greater. Moreover, there is a need to enhance the medical treatment seeking behavior of individuals with caries. However, the physiological and cognitive functions of young children are not fully developed, resulting in poor expression of their feelings, and parents are easily influenced by friends, family, hospitals, and communities. The results of the Kruskal‒Wallis analysis also revealed that the medical behavior of young children was influenced by oral health habits, emphasizing the need to strengthen the popularization and publicity of oral health knowledge among parents. Thus, the chronic disease management model of the “hospital-community-family” trinity and extended care outside the hospital is particularly important [39].

Multiple linear regression results revealed that the delay rate of urban children is lower than that of rural children because there are more ways to obtain health knowledge and more convenient medical conditions in the urban living environment. One possible approach is to increase the way and intensity of rural health education and publicity. Children with a history of dental caries have a lower delay rate than do those without a history of dental caries, indicating that knowledge of caries is helpful for timely medical treatment to a certain extent. Patients with high access to social support have lower rates of delay, highlighting the positive role of family in disease management. Perceiving the impact of caries reduces patients’ delay rates, indicating the significance of recognizing the disease. In addition to strengthening the oral health knowledge of young children with caries and their parents, parents should be urged to seek medical treatment. Similarly, the explanation of dental knowledge and the trust established during communication between doctors and nurses in hospitals are equally crucial.

In the SEM, the influence coefficient of social support on the delay of medical treatment in patients with early childhood caries was − 0.27, suggesting that enhancing social support is crucial for optimizing patients’ treatment-seeking behaviors. Some parents believe that baby teeth do not need treatment because they will just fall out. The support provided by family and others to patients affects their ability to seek medical treatment. This relationship may be related to family, friends and other individuals providing disease information and knowledge, establishing support mechanisms, and strengthening the understanding of disease progression through communication, ultimately promoting timely and early medical treatment. The importance of the external environment for cognition is also evident. Therefore, while popularizing knowledge of oral diseases, it is equally important to educate family members who affect the improvement of medical behavior among young children with dental caries. A study conducted in the United States investigated the factors influencing the dental care use among low-income preschool children. The study found that social support, particularly from family members and community organizations, played an important role in promoting dental care utilization. Similarly, this study also revealed a negative association between social support and treatment delay, highlighting the importance of social support in improving health-seeking behavior [40].

The biological-psycho-social medical model is a systematic and holistic medical model that requires medicine to view human beings as a multilevel and complete continuum. In terms of health and disease issues, it is necessary to consider the comprehensive effects of various biological, psychological, behavioral, and social factors simultaneously. Oral health is a complex concept that includes the physiological, psychological, and social adaptations of a patient’s oral health status. The synergistic effect of chronic pain and limited cognitive ability on limiting activities of daily living may occur through changes in brain morphology [41]. Children’s mental development is not yet complete, and their cognitive ability limits their assessment of their own disease status. Long-term chronic pain poses hidden dangers to their brain development, indicating that dental caries has a serious negative impact on the physical and psychological well-being of children and their parents [42]. Thwin KM et al. proposed that comprehensive oral health education could enhance guardians’ oral health knowledge, alongside fostering better oral health habits and improving the status of their children’s oral health [43]. Jones and colleagues found that children with poor oral health had significantly higher rates of dental treatment avoidance. Their research highlights the need for comprehensive oral health education programs that target both children and their caregivers. These findings resonate with the biological-psycho-social medical model and the importance of considering multiple factors when addressing oral health issues [44].

Preschool children can choose options that conform to their own psychology by recognizing five expressions in the CFSS-DS-C, which solves the problem that children cannot understand the content of the questionnaire because of their young age, thus truly reflecting the degree of fear of young children. Studies have shown that dental fear plays a mediating role between oral health-related quality of life and dental avoidance behavior, emphasizing the importance of reducing dental fear to promote medical behavior [45]. In this study, dental fear mediated social support and treatment delay, as did oral health and treatment delay. Strengthening social support can reduce the dental fear of young children with caries, promoting their medical behavior. Popularization of oral health knowledge can reduce dental fear and reduce the degree of treatment delay. Positive beliefs encourage patients to adopt positive behaviors [46]. Increased parental dental anxiety and adverse dental experiences have a negative effect on the mental health of preschool children without dental experience [47]. A higher level of dental fear was significantly associated with untreated caries experience, a delay in the age of the subject’s first visit to the dentist, low self-esteem, low oral health-related quality of life [48]. This finding is consistent with the results of this study, which identified dental fear as a direct factor influencing treatment delay. Owing to the psychological development characteristics of children, visual and auditory dispersion is effective in reducing anxiety. Visual stimulation is as important as physical sensation [49]. Minor changes in waiting room design can have a major effect on the way any child perceives the upcoming dental experience. A majority of the children preferred music and the ability to play in a waiting room. They also preferred natural light and walls with pictures. They preferred looking at an aquarium or television and sitting on beanbags and chairs and preferred plants and oral hygiene posters [50]. Virtual Reality represents an innovative approach to managing pain and anxiety, enabling dental treatment patients to immerse themselves in a virtual world, thereby using distractions to alleviate pain and anxiety [51]. Clown therapy, serving as an effective nonpharmacological intervention, significantly reduces anxiety and dental fear in pediatric patients, thereby providing valuable and practical support to pediatric dentists [52]. Nursing staff should prioritize providing patients with disease-specific health education knowledge and psychological counseling to increase their confidence in managing their conditions.

Considering the increasing prevalence of dental caries among children and the significant impact of delayed treatment on oral health, reducing the delay in seeking medical treatment in young children deserves more attention. Reducing dental fear can improve disease management and enhance the quality of life of young children. First, the important role of the external environment, such as support from parents and medical staff, in improving the medical behavior of children with early childhood caries should be recognized. Efforts should be made to increase medical staff’s professional quality and widen the scope, method, and target of education. Second, parents of young children should strengthen their learning of dental caries. The implementation of psychological care can divert children’s attention, reduce dental fear, and increase patient confidence in treatment. Finally, communities should play a crucial role in chronic disease management by disseminating disease knowledge, emphasizing the concept of oral health for overall health, and advocating timely medical treatment for caries patients.

To enhance the scalability and flexibility of the proposed interventions across diverse settings, it is crucial to take into account the local context and resources in each setting. For instance, in regions with limited healthcare access, mobile dental clinics can facilitate on-site screenings and treatments, effectively overcoming geographical barriers. In addition, community-based educational programs are needed with the goal of educating parents and caregivers about oral health and the importance of preventing ECC. To ensure cultural appropriateness, these educational efforts should align with the local population’s language and cultural subtleties, thereby fostering enhanced participation and comprehension. In areas with adequate health infrastructure, an effective strategy may be to integrate oral health education into existing maternal and child health program. Furthermore, incorporating oral health modules into school curricula has proven to be effective in instilling good oral hygiene practices from an early age. Moreover, incorporating visual storytelling and role-playing can greatly enhance children’s understanding of dental procedures. Lastly, the scalability of the intervention can be further enhanced through partnerships with local businesses and non-profit organizations. These partnerships can provide financial support, resources, or volunteering for projects. By giving due consideration to these adaptive strategies, interventions aimed at reducing treatment delays in young children with caries can be successfully implemented in a variety of settings, thereby improving oral health outcomes globally.

Although this study provides valuable insights, the potential biases arising from the single-centre study design cannot be ignored. Conducting the study in a single hospital might restrict the patient population diversity, thereby influencing the accuracy and the universal applicability of the research findings. To mitigate the constraints of future research, adopting a more comprehensive and diversified methodology is imperative. This includes expanding the geographic scope of the study to include multiple hospitals and regions to ensure a more representative sample population. Furthermore, longitudinal studies should be conducted to better understand the progression and risk factors associated with early childhood caries over time. By employing these strategies, future studies could provide a more comprehensive understanding of early childhood caries and inform the development of more effective prevention and treatment strategies.

In addition, China’s unique cultural and systemic factors may further limit the generalisability of the findings. China’s cultural values and healthcare systems differ significantly from those of many Western countries, potentially affecting parents’ and children’s approach to seeking healthcare for ECC. In Chinese culture, there is often a strong emphasis on family and collective well-being, and this may influence how parents perceive and respond to their children’s dental health issues. Parental priorities may point to other family responsibilities or concerns that may lead to delays in seeking dental care for their children, especially if they perceive dental problems to be less serious or urgent compared to other health problems. The interplay of systemic issues and cultural factors may be key factors in understanding the observed treatment delay scores as well as the impact of social support, oral health and dental fear on healthcare-seeking behaviour. To improve the applicability of the findings in the Chinese context, it is recommended that future studies incorporate cultural and systemic factors into the study design and analyses.

Early childhood caries (ECC) is one of the most common noncommunicable diseases, affecting almost half of preschool children, and its distribution is global, with geographical variations. ECC prevention is difficult and complex, and global studies have been conducted to analyze the role of social, parental, behavioral, political, medical/genetic, and psychological factors. This study has successfully formulated an innovative model to investigate the issue of treatment delay in ECC. The model encompasses a wide array of identification variables and their correlations, thereby offering a comprehensive insight into the factors that contribute to the delay in ECC treatment. While there is a growing body of research on dental treatment behavior in young children with caries, the study adds valuable insights and confirms the importance of addressing multiple factors to improve dental health outcomes. The future research direction will emphasize addressing the urban-rural disparity in seeking medical treatment for early childhood caries, particularly focusing on reducing delays in accessing care.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- CFSS-DS-C:

-

Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale-Chinese

- ECC:

-

Early Childhood Caries

- FIS-8:

-

Family Impact Scale-8

- PBHSD-C:

-

Perceived Barriers to Health Care-seeking Decision-Chinese

- P-CPQ-8:

-

Parental Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire-8

- SOHO-5:

-

Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old Children

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

The authors thank all the participants and investigators involved in this survey.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the ethics committee of the 960th Hospital of the joint logistics support force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (approval No. JZMULL2023154). All participants provided written informed consent.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Wang, M., Zhang, Y., Li, X. et al. Understanding and reducing delayed dental care for early childhood caries: a structural equation model approach. BMC Public Health 25, 523 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-21701-y