You may also like...

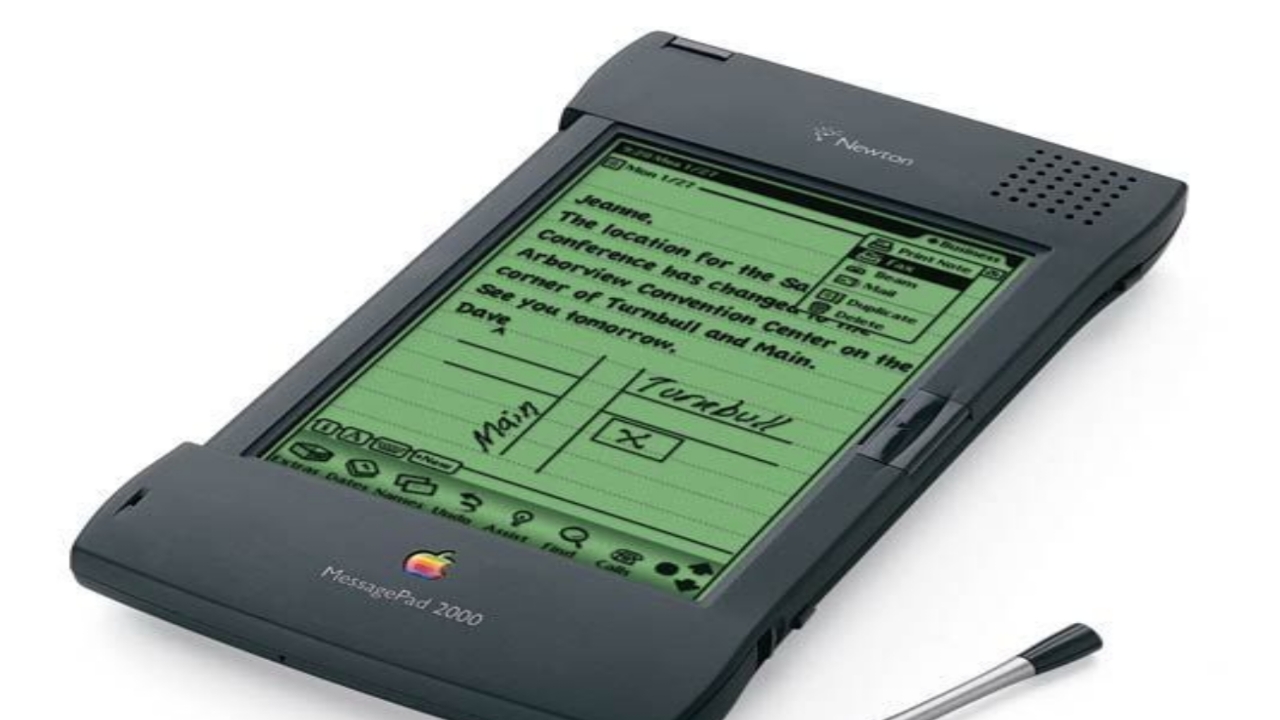

Tech Innovations That Failed, Yet Influenced Modern Technology

They flopped, they were mocked. Some were discontinued within years. But without these “failed” tech innovations, your s...

9 to 5, Remote or Business, Which Is Better?

9–5 jobs, remote work, or entrepreneurship, which career path is truly better? A grounded social commentary on stability...

South Africa Launches First-in-Human HIV Vaccine Trial, a Historic Step in Fighting HIV

South Africa, the country with the highest number of people living with HIV, launches the first-ever human trial of an H...

The Ethics of AI Dependency: What We Lose When Machines Become 'Friends'

As AI companions become more human-like, this article explores the ethical risks of emotional dependency, data privacy c...

Ex-Super Eagles Coach Unlocks 'Troublemaker' Lookman's Potential for Simeone's Atletico!

Ademola Lookman's transfer to Atlético Madrid has drawn attention to his past management issues, but former Super Eagles...

Osayi-Samuel Reveals Shocking First Words From 'Special One' Jose Mourinho!

Super Eagles star Bright Osayi-Samuel shares revealing insights into working under José Mourinho at Fenerbahçe. He detai...

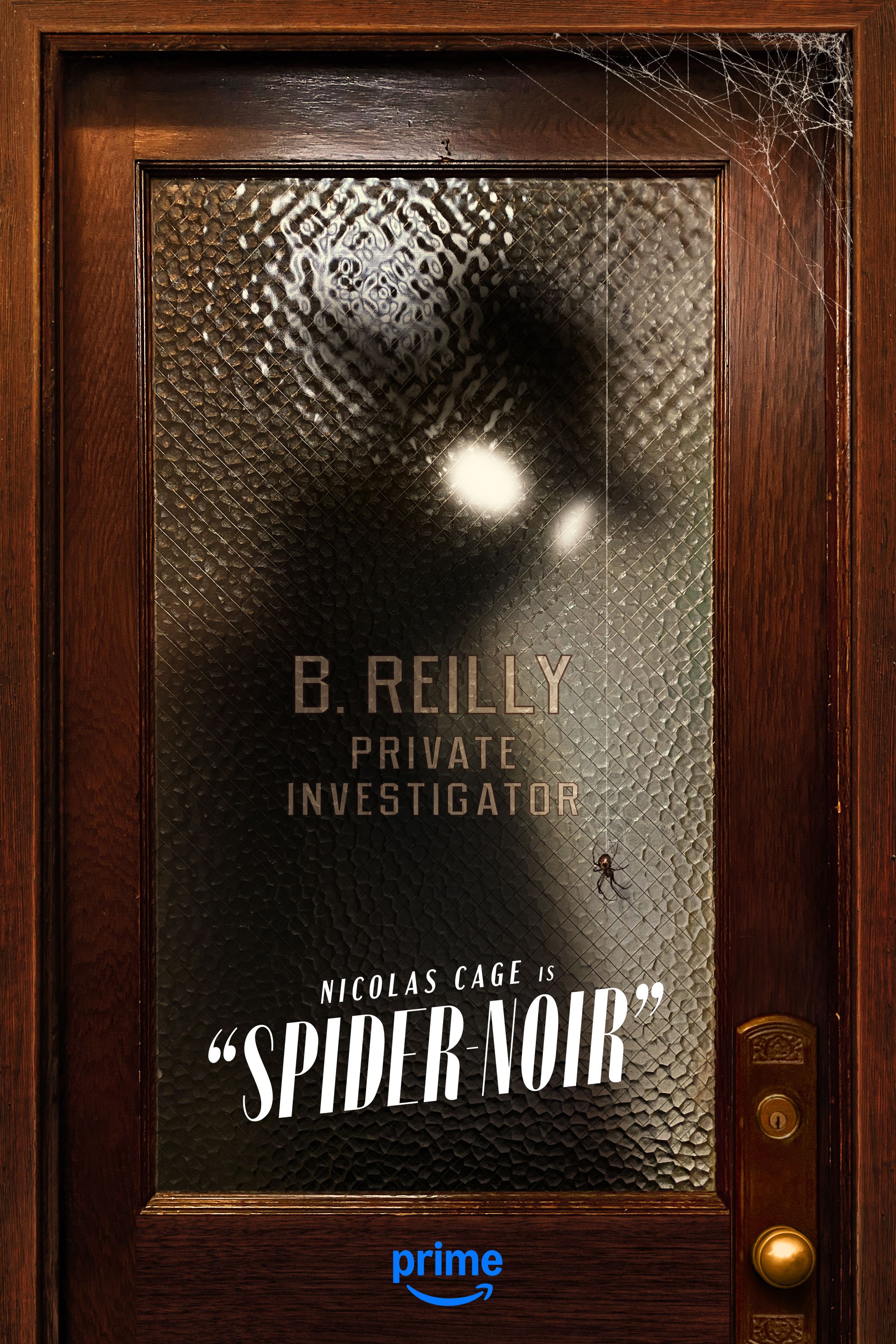

First Look! Nicolas Cage's Gritty Spider-Noir Unleashed in Jaw-Dropping Trailer!

Prime Video is set to launch its highly anticipated *Spider-Noir* series this spring, starring Nicolas Cage as Ben Reill...

Shocking Cancellation: HGTV Series Axed Over On-Set Racial Slur Controversy!

HGTV has canceled Nicole Curtis's "Rehab Addict" after the star was caught using a racial slur during filming, leading t...