The Canadian face - Paul Wells

In 2005 Kaaren and Julian Brown of Kingston, ON donated the $20,000 prize money for a new national portrait competition they had conceived. The goal was to encourage portrait art in Canada — paintings and drawings of human faces and figures, in a country whose art more often celebrates landscapes.

The Browns’ model was the Archibald Prize, an annual Australian portrait competition, at the time nearly a century old. Julian Brown, a retired chemistry professor at Queen’s University who eventually passed away in 2022, was Australian-born. The Browns had lived back in Australia for a while in the late 1960s, and followed the surprisingly acrimonious controversy the Australian competition sometimes generates. Just the sort of thing to shake up cultural life in Canada, they thought.

It turned out that in Canada, creating a durable new arts institution was easier than getting people to argue about it. The Kingston Prize has been awarded biennially, except during COVID, for nine competition rounds since 2005. A tenth round is underway. The competition’s digital archives now contain nearly 300 paintings and drawings, of consistently high quality and stylistic variety.

I’d never heard of it before. By 2023, having missed a competition year and with the competition’s co-founder Julian Brown dead, organizers were wondering whether to shut the Kingston Prize down. Instead they had a different idea, the competition’s board chair, Jason Donville, told me in an interview: spread the word and aim for renewed interest.

The first result of that decision is a book, The Kingston Prize: Canada’s Portrait Competition, published in March by WORK BOOK and Goose Lane Editions. It contains every portrait that’s made it to the competition’s final round since the prize’s inception. I found a copy by chance at my neighbourhood Chapters. It’s one of the most impressive Canadian art books in recent years, and a happy counterpoint to the other big 21st-century story in Canadian portraiture, the persistent failure to launch a national portrait gallery.

(A note about the illustrations in this post: You’re well advised to read this post on your laptop or desktop computer, where you’ll find it at this link, and where you’ll be able to click on each photo to expand it and view it in greater detail.)

Jason Donville, the Kingston Prize’s board chair, is a hedge-fund manager from Toronto. By 2023, when he got involved, the prize was running out of steam. “The mayor of Kingston was indifferent to it,” Donville told me. “Agnes Etherington” — The Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University’s art gallery — “had no interest in associating with it.” The 2023 exhibition of competition finalists was held at the Firehall Theatre in Gananoque, population 5,000, a 40-minute drive from downtown Kingston.

“And yet this was this wonderful prize,” Donville says. “The town of Gananoque had done a really good job.”

The goal of the book — which you can buy from the publisher here, or in most good bookstores — was to boost awareness of the competition outside Kingston and, uh, Gananoque from nearly zero to something more sustainable. It’s obviously a goal I find worth supporting, which is why I’m telling you about it. All the illustrations from this post depict Kingston Prize winners or finalists over the years.

There’s a startling vitality to the paintings and drawings in the Kingston Prize book. The competition is open to “any Canadian artist who depicts a Canadian citizen or permanent resident in a portrait based on a real life encounter.” There is no requirement that the subject be a person of any particular notoriety, and I recognized only two or three of the faces I saw. The three-member jury — usually an artist, somebody affiliated with a gallery, and somebody involved in arts education — is given no information about the artists who produced the works.

Two things struck me about the competition as I perused the book. First, it’s great to learn that Canada has people living in it. The main English-Canadian art auction houses move a breathtaking number of landscape paintings in a year, most from the early 20th century and many of them gorgeous, but at times you really need to keep an eye out to find any evidence of human habitation. Here’s the most recent online auction from Cowley-Abbott, and the latest from Heffel. It’s said that Canadians have long been hewers of wood and drawers of water, but Canadian art at times seems designed to remind everyone that the wood and water don’t need any Canadians to hew or draw them.

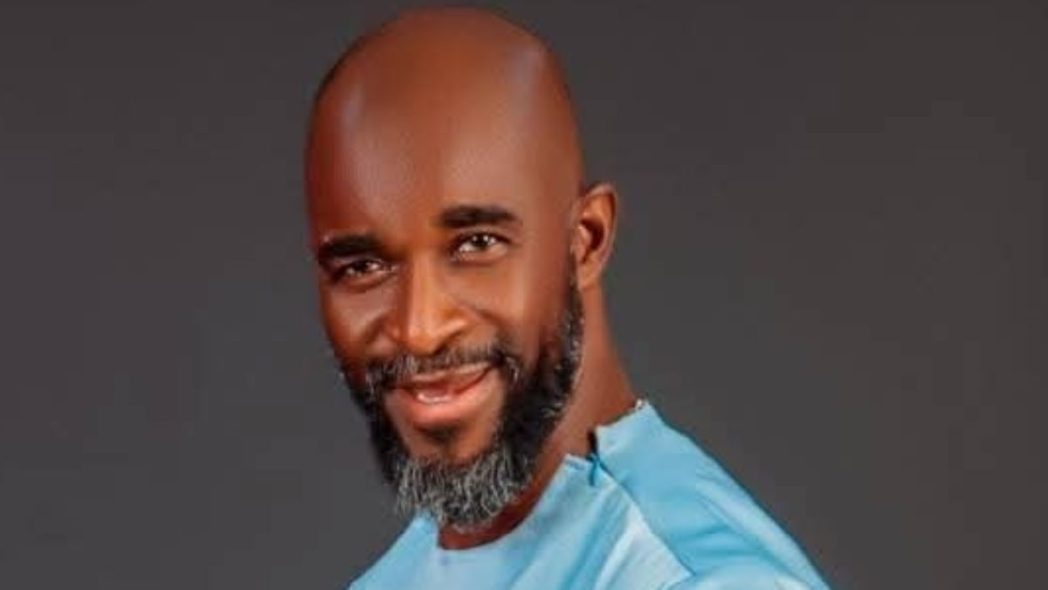

The Kingston Prize, on the other hand, brings us many dozens of paintings like this one, from 2011 finalist Steven Rosati, depicting Trevor W. Payne, the founder of the Montreal Jubilation Gospel Choir. The skill involved in producing this nearly photo-realistic portrait is obvious. But so is the care in the painting’s composition and background. I gasped as I turned the page to this painting.

I don’t want to hold up technique as the only virtue. But in an era when it’s cliché to claim that artists don’t know how to draw a circle, the technical command on display here is often formidable.

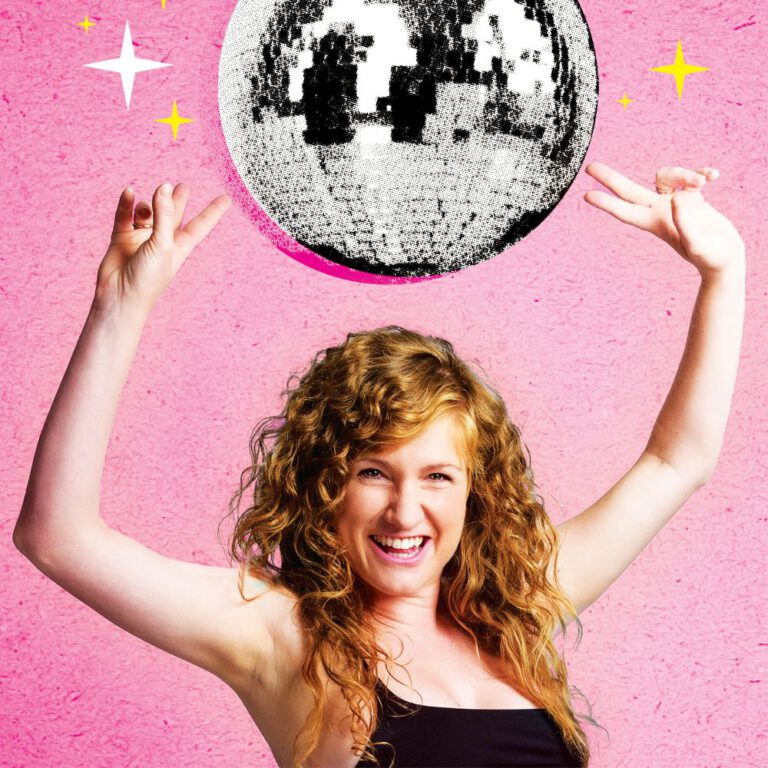

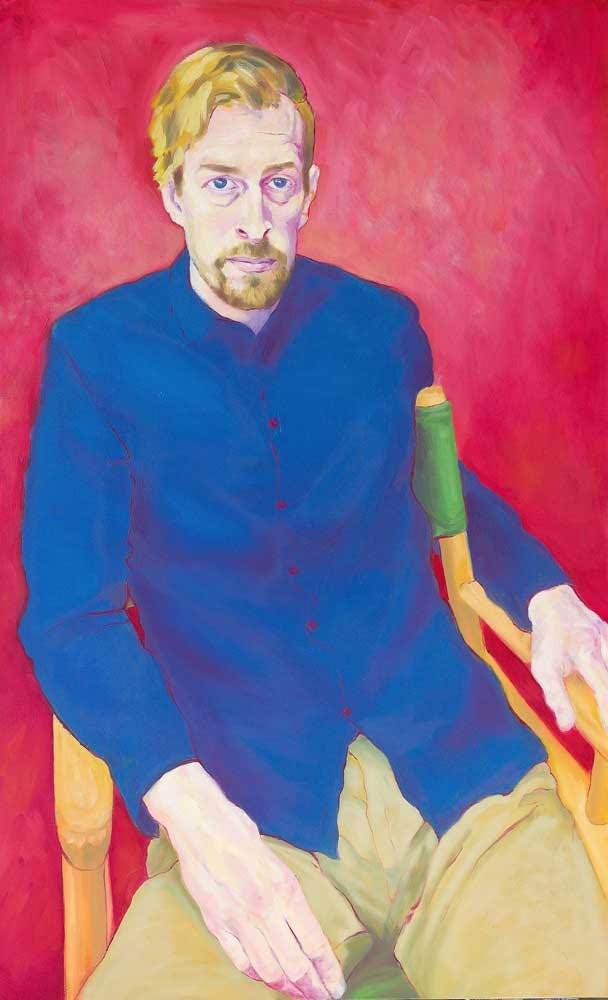

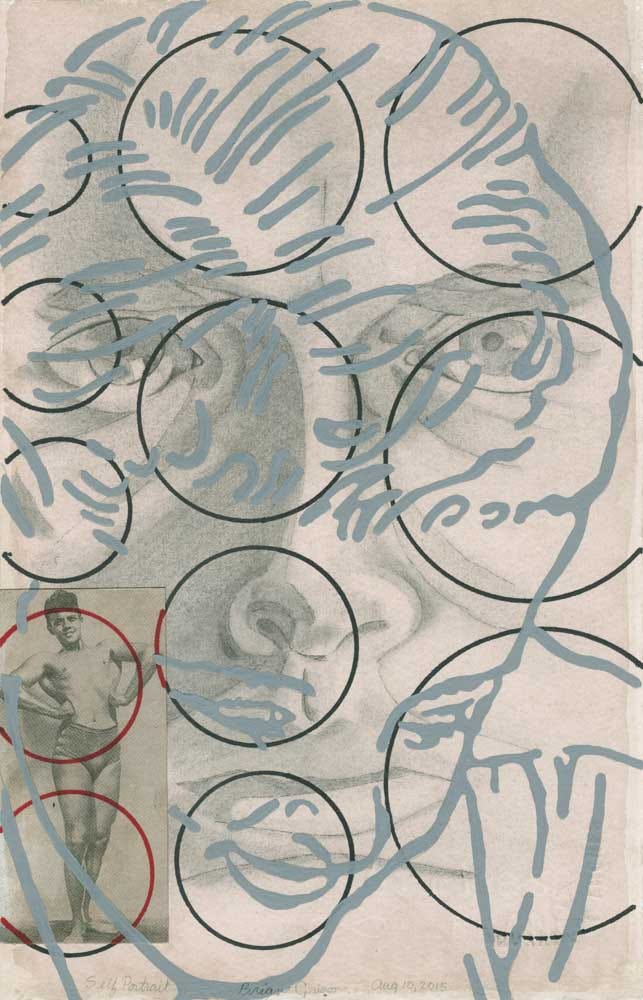

Other artists are going for other effects, or looking in other ways. Here’s a gallery of some other finalists that stood out to me.

Thanks for reading! This post is public so feel free to share it.

The other striking thing about this homage to Canadian portraits is that it exists. Another project in Canadian portraiture hasn’t been so lucky.

Last week the Toronto Star published an op-ed by Gail Lord, Canada’s leading museum consultant, calling for the creation of a National Portrait Gallery for Canada. Lord makes the best case for the project, putting it in the context of renewed Canadian nationalism, the elbows-up backlash against Donald Trump (who forced out the director of the US National Portrait Gallery) and even the Canadian gallery’s potential as a fast-track infrastructure project.

The project for a physical Canadian portrait gallery has, as Lord notes, a website that lists a sturdy board of directors. It also trails a 20-year tale of woe. In 2006 the project seemed reasonably close to fruition. A site, the former US Embassy across Wellington Street from Parliament’s Centre Block, had been selected. But Stephen Harper became prime minister and decided he wanted a national museum to be somewhere else besides Ottawa. The search for a new locale took years and led nowhere, except to passionate debates about whether it was at all acceptable for national institutions to be located outside a country’s capital city. (Spoiler: It’s fine, and common in other countries.) I think it’s fair to wonder whether Harper wanted a portrait gallery at all.

By the time Harper wore out his welcome and Justin Trudeau brought the Liberals back, the notion of a portrait gallery seemed, in some circles, unbearably stuffy and old. The old US Embassy was given another vocation.

The portrait gallery website seems to cede the argument about whether a building full of portraits of appeals-court judges and privy-council clerks would be worth it: none of the virtual gallery’s virtual exhibits has featured any member-by-right of any Canadian political or class elite. Probably this is a good thing. Whom are we kidding? If a Canadian portrait gallery had opened in 2006, surely a large number of the portraits in the collection would have been removed by now, as interpretations of Canada’s past change.

I need to emphasize here that the Kingston Prize organization does not have any position on the worthiness of a national portrait gallery, and was never meant to offer competition against any such project. Theoretically the two projects — physical gallery, biennial competition — could easily both exist in the same country. They do in Australia and Britain, sometimes circling in close orbit, sometimes ignoring each other. The comparison I offer here is entirely mine.

But it may be instructive to think about why a national portrait project has existed, almost completely ignored by the country’s political decision-makers, for 20 years while the idea of a physical place for Canada’s portrait art founders endlessly.

Surely it’s because the questions that inevitably bedevil a gallery project — where should it be? And who deserves to be in it? — have basically been ignored by the Kingston Prize. The artists decide who they want to paint. Juries decide who’s been painted well, with varying amounts of attention to why the subjects were chosen.

As for where the paintings will hang — well, with proper philanthropic or corporate or government support, the answer could be “anywhere.” Albeit probably only briefly — the portraits don’t belong to the Kingston Prize organization, so they scatter to their creators or new owners after every competition round. Jason Donville and his board are hoping that this year, and in years to come, the display of finalists might be in someplace bigger than the Firehall Theatre in Gananoque. He’s working on it. (He would even consider renaming the prize after a generous-enough donor, something that is possible because the Kingston Prize’s creators were too self-effacing to call their brainchild the Brown Prize.)

The finalists’ works might even hang, for a few weeks every two years, in a national portrait gallery, someday. But absolutely nothing says they would have to, and in the meantime, to put it gently, that’s a hypothetical situation.

You could wait forever around here for a mandate. Julian and Kaaren Brown created their mandate instead, and now we have hundreds of Canadian faces, painted hundreds of ways, that we wouldn’t have had without their initiative.

More information on the Kingston Prize here. Submissions for the competition’s 2025 edition opened in March and will remain open until Sept. 1. In theory, you could enter a painting. The value of the first prize has risen to $25,000. Details are here. Details on the Kingston Prize coffee-table book are here.