You may also like...

Man City Locks Down Star Defender: Rico Lewis Signs Massive Extension

Rico Lewis has signed a new contract extension with Manchester City, keeping him at the club until 2030, with an option ...

Blockbuster Showdown: Canelo vs. Crawford Fight Takes Center Stage

The highly anticipated undisputed super-middleweight showdown between Canelo Alvarez and Terence Crawford is set to elec...

Thanos Rises Again? Marvel Drops Shocking Hint for 'Avengers: Doomsday'

A promotional light show for *Avengers: Doomsday* has ignited fan speculation about Thanos's potential return and subseq...

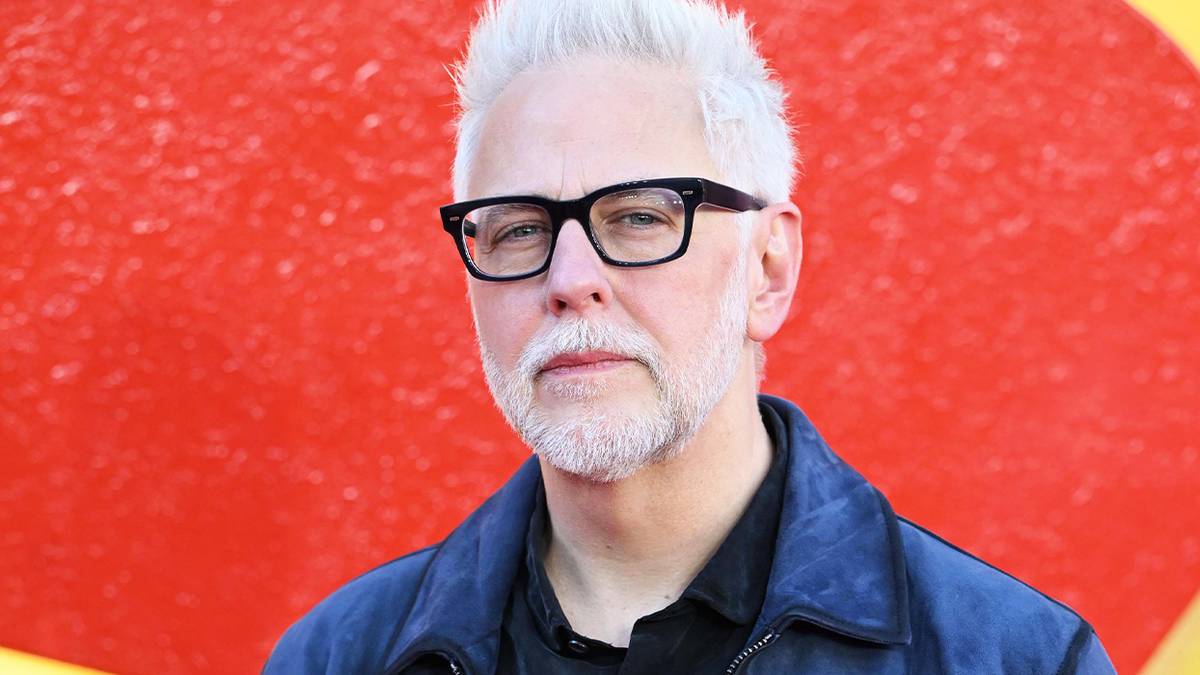

DCU Shocker! James Gunn Unveils Top Casting Choice Ahead of 'Man of Tomorrow'

DC Studios head James Gunn has hailed Milly Alcock's casting as Supergirl as potentially his best career decision. Alcoc...

KPop Phenomenon: 'Golden' Dominates UK Charts for Six Weeks Running!

The U.K. Singles Chart sees the KPop Demon Hunters' "Golden" clinch its sixth week at No. 1, making it the most successf...

Historic Comeback: Sublime Reaches First Alternative Airplay No. 1 in Nearly 30 Years!

Sublime makes a historic return to the top of Billboard's Alternative Airplay chart with "Ensenada," featuring Jakob Now...

Spinal Tap Legend Marty DiBergi's Wild Hopes for Sequel: 'Kill Each Other!'

Documentarian Martin "Marty" DiBergi discusses the highly anticipated sequel, <i>Spinal Tap II: The End Continues</i>, i...

Royal Fury Erupts! Prince Harry's Ukraine Visit Ignites William's Rage Amid Deepening Feud

Prince Harry's visit to Kyiv with the Invictus Foundation has ignited fresh tensions with Prince William, who was report...