BMC Psychology volume 13, Article number: 765 (2025) Cite this article

Psychosexual health is a fundamental component of adolescent well-being. However, research has predominantly focused on risk factors, overlooking the potential benefits of positive psychological traits. This study aimed to investigate the associations between positive psychological capital and adolescents’ psychosexual health and examine whether these relationships are moderated by autonomy and gender.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted between December 2023 and April 2024 in Zunyi City, Guizhou Province, China. Using convenience sampling, 8,205 students were recruited from 10 junior and senior high schools representing both urban and rural regions. Participants completed the Chinese versions of the Positive Psychological Capital Questionnaire, Autonomy Questionnaire, and Adolescent Psychosexual Health Questionnaire. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 and PROCESS v3.5.

After data cleaning based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 7,910 valid responses were retained, yielding a validity rate of 96.40%. The final sample had a mean age of 13.99 years (SD = 1.13), with 50.1% male and 49.9% female participants. Positive psychological capital was significantly and positively associated with psychosexual health: hope (r = 0.530, p < 0.001), optimism (r = 0.505,p < 0.001), self-efficacy (r = 0.467 p < 0.001), and resilience (r = 0.449, p < 0.001). Autonomy significantly moderated the following associations: hope (β = 0.040; p < 0.001), self-efficacy (β = 0.086; p < 0.001), resilience (β = 0.086,p < 0.001), and optimism (β = 0.091; p < 0.001). Gender did not show a significant moderating effect.

Positive psychological capital play a vital role in enhancing adolescents’ psychosexual health. Autonomy amplifies these beneficial effects and should be prioritized in future interventions aimed at promoting adolescent mental and sexual well-being.

Psychosexual health is a complex and multidimensional concept that integrates elements of both sexual and mental health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), sexual health is a multifaceted construct of significant importance in psychology and medicine, encompassing physical, emotional, mental, and social aspects of sexuality [1]. Mental health is defined as a state of well-being that enables individuals to cope with life’s stresses, realize their potential, learn effectively, work productively, and contribute to their community [2]. Therefore, psychosexual health can be understood as the integration of these two aspects, focusing on psychological well-being within the context of sexual development, identity, and interpersonal relationships. Importantly, psychosexual health encompasses not only the absence of dysfunctions but also the presence of positive aspects such as the capacity for intimacy, mutual respect in relationships, and the development of a healthy sexual self-concept. Adolescence is a critical period for psychosexual development that involves navigating complex changes in biological, psychological, and social dimensions, making this stage pivotal for establishing a foundation for lifelong psychosexual health [3, 4].

Research has highlighted various internal and external factors that influence adolescent psychosexual health. Internal factors, such as early or late pubertal development, are linked to increased risks of depression and emotional instability, particularly when adolescents perceive themselves as different from their peers [5, 6]. Adverse experiences such as childhood sexual abuse, which is prevalent among Chinese female adolescents, are associated with higher rates of depression, suicidality, and risky behaviors [7]. This lack of sexual awareness, compounded by social stigma, contributes to emotional instability, stress, and strained relationships with peers, partners, and family members [8]. Additionally, social anxiety and depressive symptoms can negatively affect the quality of sexual intimacy and overall psychosexual well-being [9].

Externally, factors such as family environment, peer influences, and societal norms play dual roles, either providing a supportive context for healthy psychosexual development or exacerbating vulnerabilities [8]. The social networks that adolescents build within their families, schools, peer groups, and communities provide essential support, norms, and protective mechanisms for psychosexual health [10, 11]. For instance, open communication within family social capital and parental care not only help adolescents understand sexual behaviors and sexual health more accurately but also guide them in developing a positive sexual self-identity [4].

Many studies have focused on the relationship between adolescent psychosexual health and negative psychological issues, such as emotional problems and distorted perceptions. Research has also explored the impact of family upbringing on adolescents. However, only a few studies have examined the influence of positive psychological traits on psychosexual health. This study primarily investigates the effect of positive psychological capital on psychosexual health, aiming to understand the mechanisms through which adolescents’ positive psychological qualities influence their psychosexual well-being. Additionally, it explores the moderating roles of gender and autonomy in this relationship.

Positive psychological capital pertains to the psychological resources and capabilities inherent in an individual that can be harnessed to navigate challenges, attain objectives, and sustain a positive mindset. Positive psychological capital encompasses positive psychological traits and attitudes that contribute to an individual’s overall psychological well-being. The foundational elements comprising elevated self-efficacy, optimism, hope, and resilience are recognized as pivotal components [12]. These elements are thought to play a role in an individual’s holistic well-being, psychological state, and proficiency across diverse domains, such as work, education, and personal relationships [13].

Self-efficacy is the belief in one’s ability to accomplish tasks or goals and plays a key role in motivation and goal-directed behavior [14]. For adolescents, higher self-efficacy promotes confidence in sexual development and relationships, helping them navigate changes in identity, emotions, and physical development [15, 16]. It fosters a proactive attitude toward sexual health education, reducing risky behaviors and supporting healthier sexual self-concepts, thereby improving overall psychosexual health [17]. Hope involves goal-directed thinking and the belief in one’s ability to achieve desired outcomes [12]. Hope motivates adolescents to pursue positive sexual experiences and maintain healthy relationships. It helps them set clear, realistic goals related to sexual health, such as practicing safe sex and building meaningful relationships [18]. Hope provides the mental framework to overcome challenges such as peer pressure and societal expectations, promoting healthier sexual behaviors [19]. Resilience refers to the ability to adapt and recover from adversity [20]. Resilient adolescents are better able to cope with challenges in their sexual development, such as rejection, trauma, or peer pressure. Resilience helps them maintain a positive sexual identity, reduce risky behaviors, and manage mental health issues such as anxiety or depression, contributing to better psychosexual health [21]. Optimism is a positive outlook on life and the expectation of favorable outcomes [22]. Optimistic adolescents approach sexual experiences with confidence, viewing sexual development as a natural and healthy process. This mindset fosters trust, healthy relationships, and responsible sexual behaviors [23]. Additionally, optimism helps buffer against negative emotions such as guilt or shame, encouraging informed decisions and enhancing overall sexual and mental health [24, 25].

In the absence of direct evidence linking the four dimensions of positive psychological capital to psychosexual health, the objective of this study is to explore how hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism influence psychosexual health in adolescents. The research hypotheses are as follows:

H1: A positive correlation between hope and psychosexual health in Chinese adolescents.

H2: A positive correlation between self-efficacy and psychosexual health in Chinese adolescents.

H3: A positive correlation between resilience and psychosexual health in Chinese adolescents.

H4: A positive correlation between optimism and psychosexual health in Chinese adolescents.

Autonomy, defined as an individual’s right to make decisions and take actions independently, free from external pressure or constraints, plays a crucial role in psychological well-being and health [26].

When autonomy is high, adolescents are empowered to pursue their sexual health goals independently by seeking information, setting boundaries, and forming relationships that align with their values [27]. Autonomy fosters intrinsic motivation and personal control, strengthening the positive relationship between hope and psychosexual health. With the freedom to make decisions about their sexual health, adolescents approach experiences with confidence and foresight, enhancing well-being and reducing risky behaviors [28]. High autonomy allows them to apply self-efficacy in sexual health contexts, such as negotiating safe practices, communicating with partners, and resisting peer pressure. This control strengthens their ability to manage challenges and make informed decisions, reducing vulnerability to risky behaviors while enhancing sexual well-being [29, 30]. Autonomy supports resilience by helping adolescents navigate challenges independently. For example, those with high autonomy are more likely to seek support during emotional distress or relationship conflicts, fostering healthy emotional regulation and protective behaviors [31, 32]. This independence enhances the impact of resilience on psychosexual health, enabling adolescents to maintain a positive sexual self-concept and thrive in their development despite setbacks. Finally, autonomy amplifies the benefits of optimism by encouraging adolescents to view challenges as growth opportunities and make proactive value-aligned decisions [32, 33]. This sense of control reinforces the positive effects of optimism on psychosexual health, promoting healthier sexual behaviors and emotional well-being. Autonomy strengthens optimal psychosexual health relationships by empowering adolescents to act consistently with their beliefs and goals.

As a developmental milestone, autonomy is essential in maximizing the benefits of psychological capital, supporting adolescents in their journey toward healthy sexual development and overall well-being. Therefore, nurturing autonomy in adolescents can significantly contribute to the promotion of positive sexual outcomes and mental health. This study assumes that autonomy moderates the relationship between psychological capital and psychosexual health. The hypotheses are as follows:

H5a: Autonomy moderates the relationship between hope and psychosexual health in adolescents.

H5b: Autonomy moderates the relationship between self-efficacy and psychosexual health in adolescents.

H5c: Autonomy moderates the relationship between resilience and psychosexual health in adolescents.

H5d: Autonomy moderates the relationship between optimism and psychosexual health in adolescents.

Some studies have highlighted significant gender differences in coping mechanisms, emotional expression, and societal expectations, all of which play a role in how adolescents navigate psychosexual development.

For instance, studies indicate that sexual self-efficacy varies by gender; females generally exhibit higher levels of sexual refusal self-efficacy, whereas males tend to have greater confidence in condom use self-efficacy [34, 35]. Additionally, females may benefit more from resilience as a psychological resource [36], likely due to their increased vulnerability to emotional stressors such as depression and anxiety, as documented in prior research [37]. Notably, research indicates a higher likelihood of depression in females compared to males [38]. Conversely, males might derive greater benefits from optimism and goal-oriented strategies because of societal expectations that emphasize problem-solving and independence, and men are more optimistic than women [39]. Females, with their emotional awareness and relational focus, use hope to build connections and seek support for sexual health issues [40]. Males, reflecting norms of independence, apply hope to address these concerns through practical strategies [41].

Gender differences, which encompass variations in emotional expression, coping styles, and societal expectations, play a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ mental health. However, there is a research gap concerning the intricate mechanism of gender’s influence on the interplay between positive psychological capital and psychosexual health. In response to this gap, this study hypothesizes that gender moderates the relationship between hope, resilience, self-efficacy, optimism, and psychosexual health. It is postulated that these gender-specific moderating effects have profound implications. The specific hypotheses are as follows:

H6a: Gender moderates the association between hope and psychosexual health of adolescents, with females demonstrating elevated levels compared to males.

H6b: Gender moderates the association between self-efficacy and psychosexual health of adolescents, with females demonstrating elevated levels compared to males.

H6c: Gender moderates the association between resilience and psychosexual health of adolescents, with females demonstrating elevated levels compared to males.

H6d: Gender moderates the association between optimism and psychosexual health of adolescents, with males demonstrating elevated levels compared to females.

Finally, although the psychosexual health measure includes three theoretically distinct subdimensions—sexual knowledge, sexual attitude, and psychosexual adjustment—these were modeled as a single latent variable in the structural model. This decision was based on both theoretical and empirical considerations.

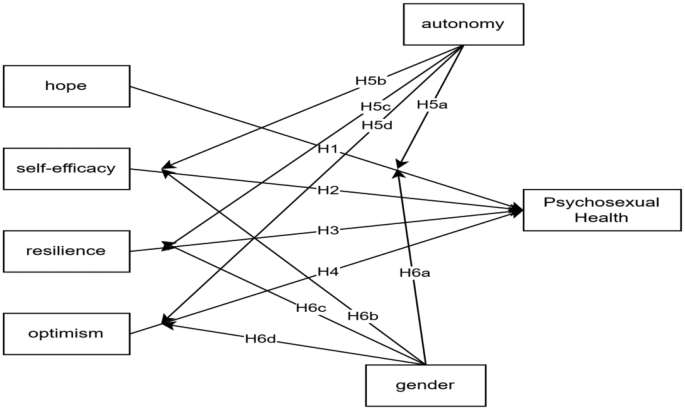

Theoretically, adolescent psychosexual health is considered a holistic construct that reflects the overall integration of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of sexuality development. Empirically, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses indicated that the three subdimensions loaded significantly onto a common factor, justifying their aggregation into one outcome indicator. This modeling approach also improves parsimony and model stability in the context of complex mediation and moderation analyses. Figure 1 presents the model for the hypothesis based on this review.

Research model (IV: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, optimism; DV: psychosexual health; Moderators: autonomy and gender)

The selection of gender and autonomy as moderators in this study is grounded in established psychological theories and supported by prior empirical research. According to Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory [42], adolescent development is influenced by individual characteristics and environmental factors. Gender, as a salient individual characteristic, shapes how adolescents experience psychological and social processes, including the internalization and expression of psychosexual development [43]. Research has shown that boys and girls often differ in their emotional coping strategies, self-concept, and perceptions of psychological resources such as hope and self-efficacy [44, 45], which may lead to differential pathways to psychosexual health.

Additionally, self-determination theory highlights autonomy as a basic psychological need essential for healthy development and well-being [46]. Autonomy reflects an individual’s perceived ability to make independent decisions and regulate behavior according to personal values, which is particularly relevant in the psychosexual health domain [46]. Previous research has demonstrated that autonomy enhances adolescents’ ability to effectively apply psychological capital to navigate complex social and emotional contexts, including those related to sexuality and identity formation [47, 48]. Therefore, autonomy is theoretically expected to moderate the relationship between positive psychological capital and psychosexual health.

Together, these theoretical frameworks provide a solid foundation for examining gender and autonomy as moderators in the relationship between positive psychological capital and adolescent psychosexual health.

This study follows the operational definition of “adolescent” as proposed by the WHO, which refers to individuals aged 10 to 19 years [49]. Based on this definition and the structure of the Chinese education system, primary school typically includes ages 6–12, junior high school includes ages 12–15, and senior high school includes ages 16–18. Adolescents enrolled in junior and senior high schools were selected as the target population. In China, junior and senior high school students are generally aged 12–18. However, slight age deviations are common, owing to factors such as delayed school entry or grade retention. Therefore, a small number of 19 years old students were also included in our sample, which remains consistent with the WHO’s age-based definition of adolescence.

The participants were selected from ten educational institutions, including both urban and rural junior and senior high schools in Zunyi City, Guizhou Province, China, between December 17, 2023, and April 29, 2024. The questionnaires were distributed using the WENJUANXIN platform, and participants accessed them by scanning a QR code on their mobile phones or computers.

In total, 8,205 questionnaires were collected. After data cleaning, 7,910 valid questionnaires remained, yielding a validity rate of 96.40%. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for questionnaire screening were as follows:

Inclusion criteria:

(1) Currently enrolled as a junior or senior high school student in China;

(2) Provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria:

(1) Not enrolled in junior or senior high school;

(2) Completed the questionnaire in less than 300 s, which may indicate random or inattentive responses;

(3) Selected the same response option for all items, suggesting response bias.

Based on the model structure and the number of predictors, we assessed the required sample size using both the “10 times rule” and an a priori power analysis [50]. The most complex part of the model includes 12 predictors for the endogenous variable (psychosexual health), suggesting a minimum of 120 cases based on the 10 times rule. Furthermore, a power analysis using G*Power (f² = 0.02, a = 0.05, power = 0.95, and 12 predictors) indicated a minimum required sample size of 1,076. Thus, our final sample size of 7,910 participants exceeds both thresholds, ensuring sufficient statistical power and model reliability.

The study was approved by the Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC) under the approval number UM.TNC2/UMREC_3076. Data were collected from January 10, 2024, to April 29, 2024. All questionnaires were completed voluntarily, and the option of whether to answer voluntarily was set before the questionnaire began to be answered, so that if they did not want to, they could not continue. Oral consent was obtained from the students, their parents or legal guardians, and the respective schools. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants under the age of 16. We have ensured that our study adheres to ethical guidelines regarding minors’ participation. The data collection process complied with local laws and regulations.

This study employed a quantitative cross-sectional research design. The data analysis was conducted in several steps:

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics, normality tests, and correlation analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the bivariate relationships between all key variables, including the dimensions of positive psychological capital and psychosexual health.

Moderation analyses

Moderating effects of autonomy and gender were examined using PROCESS for SPSS, developed by Hayes [51]. Prior to conducting moderation analyses, all variables involved in the interaction terms were standardized (converted into z-scores) using SPSS. These standardized variables were then used in PROCESS analyses to obtain standardized regression coefficients.

Post-hoc visualization

For variables that demonstrated significant moderating effects in the analysis, simple slope analyses were subsequently conducted to further probe the nature of these interactions. This approach allowed us to examine how the strength and direction of the relationship between the predictor (positive psychological capital) and the outcome variable (psychosexual health) varied at different levels of the moderator variables (gender and autonomy). The results of these simple slope analyses were then visualized through interaction plots, providing a clearer and more intuitive understanding of how the moderating variables influenced the predictive relationships.

All significance tests were conducted using a 95% confidence interval (p < 0.001 as the threshold for statistical significance), and effect sizes were reported where applicable.

The Positive Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PPCQ) comprises four dimensions: self-efficacy, resilience, hope, and optimism. The formal PPCQ consists of 26 items, including 7 items each for self-efficacy and resilience (e.g., Many people appreciate my talents; I don’t like getting angry) and 6 items each for optimism and hope (e.g., I actively learn and work to achieve my ideals; When the situation is uncertain, I always anticipate positive outcomes). The Cronbach’s coefficient for the whole scale was 0.9, and the Cronbach’s coefficients for the four subscales were 0.86, 0.83, 0.80, and 0.76. Both subscale and total scores were calculated. The total score ranges from 26 to 156, with higher scores indicating greater positive psychological capital [52]. This scale has been used many times by Chinese researchers and has demonstrated stable reliability and validity, making it a reliable questionnaire for measuring psychological capital [53].

The Psychosexual Health Questionnaire for Adolescent Students (PSHQ-AS) consists of three sub-scales: sexual cognition, sexual values, and sexual adaptation. The PSHQ-AS had a total of 46 items, of which 17 were reverse scored and 4 pairs of lie detector questions (e.g., I understand the physiological structure of the human body; I have knowledge about contraception), and was based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from complete nonconformity (1 point) to complete conformity (5 points). The internal consistency coefficients, retest reliability, and split-half reliability indices of the scale were 0.822, 0.856, and 0.75, respectively. The higher the total score on the scale, the higher the level of psychosexual health [54, 55]. The total score ranged from 46 to 230, with higher scores indicating better psychosexual health. Subscale scores (sexual cognition, sexual values, and sexual adjustment) were calculated for factor structure validation, but the total score was used in the main analysis as a unified measure, consistent with prior literature. This scale has been used in several studies in China, all of which have demonstrated good reliability and validity [56, 57].

In this study, only the Autonomy subscale of the Chinese version of the Basic Psychological Needs Scale was used, which is consistent with our theoretical focus on autonomy as a moderator. This use of a subscale rather than the full scale is consistent with prior empirical studies that focus on specific psychological needs (e.g., autonomy) as distinct constructs [58]. The subscale consists of 6 items (e.g., “I often feel that I can be myself in daily life”), rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true, 7 = very true). Its test–retest reliability was 0.75, indicating good temporal stability. Moreover, the autonomy scores showed significant positive correlations with related psychological well-being indicators, including life satisfaction and sense of coherence, supporting the construct validity of this subscale. Given the small number of items and their demonstrated stability and validity, the measure is considered acceptable and appropriate for the current research context [59].

Harman’s single-factor test was used to assess the presence of common method bias. The criterion for determining significant common method bias is whether the first factor explains more than 50% of the total variance [60]. Unrotated exploratory factor analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for 21.006% of the total variance, which is well below the recommended threshold of 40%. This result suggests that common method bias is not a serious concern in the present study.

The study gathered 8205 questionnaires, of which 7,910 were deemed valid, yielding a validity rate of 96.40%. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the study participants, encompassing age distribution, gender representation, and academic year enrollment. Participants’ ages ranged from 12 to 19 years, with the majority (73.8%) concentrated in the 13 14 year range. The mean age was 13.99 years, with a standard deviation of 1.132. The gender distribution was well-balanced, comprising 50.1% male and 49.9% female participants. Participants were enrolled across various academic years, with the majority enrolled in years 7 (43.1%) and 8 (41.5%). The overall mean academic year was 1.84, with a standard deviation of 0.993.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients for the main variables. The mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) for each variable are as follows: psychosexual health (M = 3.63, SD = 0.443), autonomy (M = 4.429, SD = 0.806), self-efficacy (M = 4.481, SD = 0.802), resilience (M = 4.766, SD = 0.783), hope (M = 5.171, SD = 0.728), and optimism (M = 4.899, SD = 0.762). These values indicate that adolescents in this sample generally reported relatively high levels of psychosexual health and psychological capital.

The correlation analysis reveals significant positive associations among the key study variables. Psychosexual health is significantly and positively correlated with self-efficacy (r = 0.467,p < 0.01), resilience (r = 0.449,p < 0.01), hope (r = 0.530,p < 0.01), optimism (r = 0.505,p < 0.01), and autonomy (r = 0.410,p < 0.01). These findings provide empirical support for hypotheses H1–H4.

Additionally, autonomy shows strong positive correlations with positive psychological capital: self-efficacy (r = 0.602,p < 0.01), resilience (r = 0.606,p < 0.01), hope (r = 0.567,p < 0.01), and optimism (r = 0.597,p < 0.01). These results suggest that adolescents with higher levels of autonomy tend to report more positive psychological resources.

Gender, coded as 1 for males and 2 for females, also shows statistically significant correlations with several variables, although the effect sizes are relatively small. Gender is positively associated with psychosexual health (r = 0.109,p < 0.01), indicating that female adolescents tend to report slightly higher levels of psychosexual health. In contrast, gender is negatively correlated with self-efficacy (r = -0.156,p < 0.01), resilience (r = -0.182,p < 0.01), optimism (r = -0.073,p < 0.01), and autonomy (r = -0.054,p < 0.01), while no significant correlation is observed with hope (r = -0.016,p > 0.01). These results suggest that female adolescents may perceive lower levels of some psychological capital components than their male counterparts, although the differences are not substantial.

When analyzing the moderating effect, gender was first transformed into dummy variables before conducting the related analysis (male = 0, female = 1) and mean-central analysis of the data.

The mathematical formulation of this moderation effect test is expressed as follows [61, 62]:

$$\:Y={b}_{0}+({b}_{1}+{b}_{3}M)X+{b}_{2}M+e$$

Y: Dependent variable.

X: Independent variable.

M: Moderator.

b0, b1, b2, b3: Coefficient of regression.

b1 + b3M: Slope.

e: Error term.

According to Table 3, The model were found to be statistically significant (F = 117.711, ∆R2 = 0.010,p < 0.001). A significant interaction effect was evident between autonomy and hope (β = 0.040,p < 0.001), indicating the presence of a meaningful moderating role of autonomy in the association between hope and psychosexual health. The interaction effect between gender and hope is not significant (β = 0.000,p > 0.001), gender does not change the effect of hope on psychosexual health. This study supports H5a but not H6a.

In Table 4, the results revealed statistical significance (F = 107.214,∆R² = 0.010,p < 0.001). Additionally, a noteworthy interaction effect between autonomy and self-efficacy was observed (β = 0.086,p < 0.001). Autonomy had a moderating role in self-efficacy, while psychosexual health had a significant moderating role. The interaction between gender and self-efficacy was not significant (β = 0.000,p > 0.001), and gender does not change the effect of self-efficacy on psychosexual health. The study supports H5b and does not support H6b.

In Table 5, notable statistical significance was observed (F = 106.105, ∆R² = 0.010,p < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant interaction effect between autonomy and resilience was identified (β = 0.086,p < 0.001), signifying the presence of a substantial moderating role for autonomy. It is worth noting that the interaction between gender and resilience did not reach significance (β = 0.000,p > 0.01), indicating that gender does not influence the impact of resilience on psychosexual health. The findings support H5c but do not align with H6c.

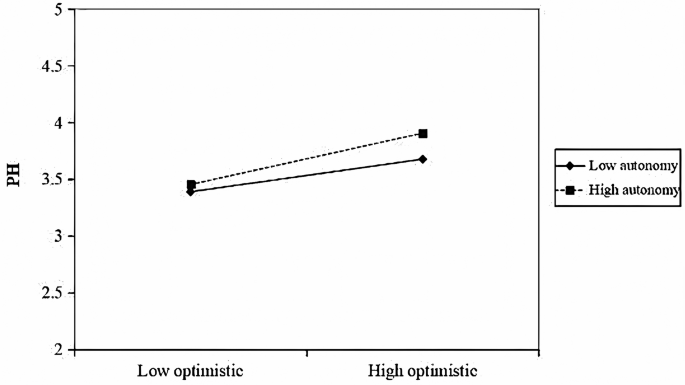

Table 6 revealed statistically significant results (F = 127.441, ∆R2 = 0.011,p < 0.001). There was a significant interaction effect between autonomy and optimism (β = 0.091,p < 0.001), which indicates that autonomy has a significant moderating effect on optimism and psychosexual health. moderating role and the moderating role was significant. The interaction between gender and optimism was not significant (β = 0.000,p > 0.001); gender does not change the effect of optimism on psychosexual health. The study supports H5d but not H6d.

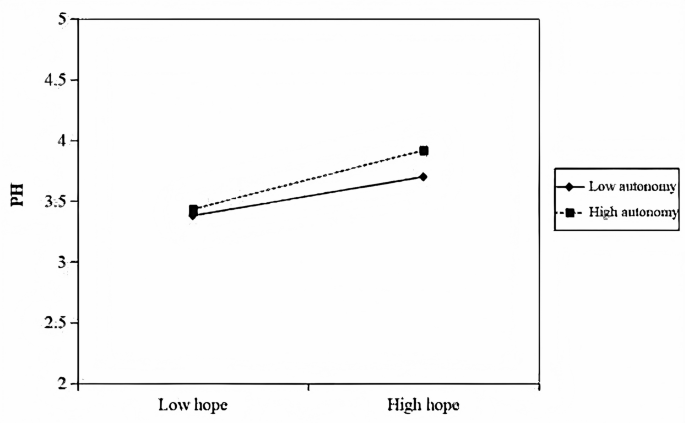

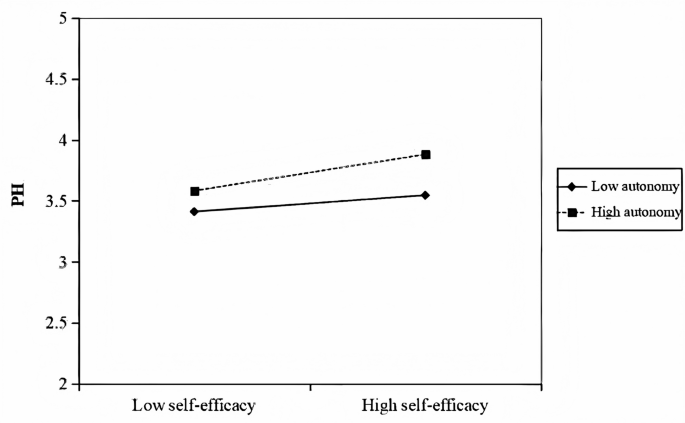

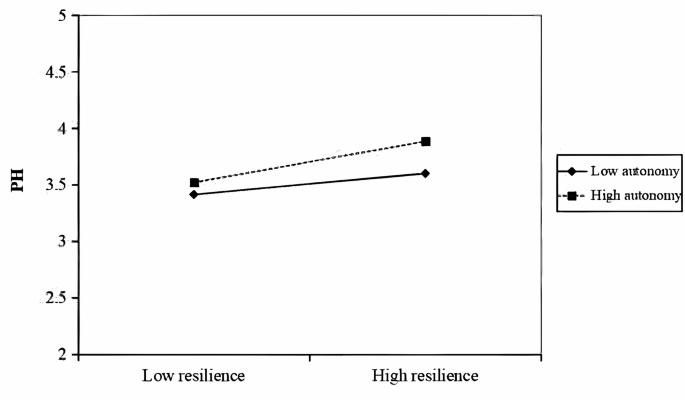

By examining intercepts across multiple levels, fluctuations in the moderator’s effect on the dependent variable can be scrutinized. When a moderating effect is present, intercept plots assist in understanding how the moderator influences the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, revealing variations across different conditions. Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 provide visual representations of the moderating effects.

To further explore the nature of the interaction, slopes were plotted for low and high levels of autonomy and resilience using standardized parameter estimates (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5). Compared to low autonomy, high autonomy exhibited more pronounced moderating effects of hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism on psychosexual health. Increased autonomy amplified the positive effects of these four factors on psychosexual health, whereas decreased autonomy attenuated their facilitative effects.

Moderation analysis revealed that autonomy significantly influenced the strength of the relationship between hope and psychosexual health. To further probe this interaction, simple slope analyses were conducted at three levels of autonomy: low (–1 SD), mean (0 SD), and high (+ 1 SD). The results showed a clear pattern: as autonomy increased, the positive effect of hope on psychosexual health became stronger. Specifically, at low levels of autonomy, the effect of hope on psychosexual health was 0.360 (p < 0.001); at the mean level of autonomy, the effect increased to 0.453 (p < 0.001); and at high levels of autonomy, the effect further strengthened to 0.547 (p < 0.001). These results indicate that adolescents with higher levels of autonomy benefit more from hope in promoting their psychosexual health, suggesting that autonomy amplifies the protective and promotive functions of hope in this developmental domain (Fig. 2).

The linear moderating effect of autonomy on hope and psychosexual health. Note: PH = Psychosexual Health

Autonomy moderated the relationship between self-efficacy and psychosexual health. At low levels of autonomy (–1 SD), the positive effect of self-efficacy on psychosexual health was relatively weak (β = 0.250,p < 0.001). At the mean level of autonomy (0 SD), this effect increased (β = 0.342,p < 0.001), and it became notably stronger at high levels of autonomy (+ 1 SD) (β = 0.434,p < 0.001). These findings indicate that greater autonomy enhances the positive influence of self-efficacy on adolescents’ psychosexual health (Fig. 3).

The linear moderating effect of autonomy on self-efficacy and psychosexual health. Note: PH = Psychosexual Health

Autonomy moderated the relationship between resilience and psychosexual health. When autonomy was low (–1 SD), the positive effect of resilience on psychosexual health was relatively modest (β = 0.210,p < 0.001). This effect became stronger at the mean level of autonomy (0 SD) (β = 0.310,p < 0.001), and it was further amplified under high autonomy conditions (+ 1 SD) (β = 0.411,p < 0.001). These results suggest that adolescents with higher levels of autonomy are better able to leverage their resilience to enhance their psychosexual well-being (Fig. 4).

The linear moderating effect of autonomy on resilience and psychosexual health. Note: PH = Psychosexual Health

Autonomy moderated the relationship between optimism and psychosexual health. Under low autonomy, the positive effect of optimism on psychosexual health was weaker (β = 0.324, p < 0.001). This effect became stronger at the mean level of autonomy (0 SD) (β = 0.419,p < 0.001). However, under high autonomy, the effect was significantly stronger (β = 0.513, p < 0.001). These results suggest that higher autonomy amplifies the positive relationship between optimism and psychosexual health (Fig. 5).

In summary, the findings underscore the critical role of autonomy as a moderator, enhancing the positive effects of hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism on psychosexual health.

The linear moderating effect of autonomy on optimism and psychosexual health. Note: PH = Psychosexual Health

This study investigated the effects of positive psychological capital on adolescents’ psychosexual health and examined the moderating roles of gender and autonomy. As hypothesized, each of the four dimensions of positive psychological capital—hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism—was significantly positively associated with psychosexual health. These findings reinforce the notion that positive psychological capital is an important internal psychological asset that contributes to adolescents’ healthy psychosexual development.

Importantly, autonomy was found to significantly moderate the relationships between all four positive psychological capital components and psychosexual health. Specifically, the positive effects of hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism on psychosexual health were stronger among adolescents with higher levels of autonomy. Although the interaction effect sizes were statistically small, they remain meaningful in psychological research, particularly when interpreted alongside simple slope analyses. These post-hoc analyses revealed that the estimated slopes at different levels of autonomy exceeded the conventional threshold for a small effect size, indicating that the buffering and promotive functions of positive psychological capital are amplified when adolescents perceive greater self-determination and volitional functioning. In other words, autonomy appears to be a key contextual resource that enhances the efficacy of internal psychological strengths in promoting psychosexual well-being.

While gender also showed a statistically significant interaction with some positive psychological capital dimensions, the observed effect sizes were negligible. This suggests limited practical significance, reinforcing the need for caution when interpreting statistically significant interaction effects in large samples without sufficient effect size justification.

Taken together, these findings underscore that positive psychological capital functions as a vital promotive factor in adolescent psychosexual health. Hope fosters future orientation and goal-directed behavior; self-efficacy equips youth to handle challenges assertively; resilience buffers stress and emotional setbacks; and optimism sustains positive expectations about interpersonal relationships. Autonomy strengthens these effects by creating a psychological context that supports personal agency, intrinsic motivation, and adaptive coping.

By acknowledging both the statistical and practical significance of the interaction effects, this study offers a nuanced understanding of how adolescents’ internal strengths and contextual resources jointly contribute to their psychosexual health. The results suggest that fostering autonomy in adolescents may enhance the positive impact of positive psychological capital, promoting healthier and more adaptive psychosexual development.

Our findings align with and extend previous research across all four dimensions of psychological capital. In terms of hope, our results support Groenewald’s conclusion that hope motivates adolescents to seek positive sexual experiences and maintain healthy relationships [18]. While Hill emphasized the role of hope in overcoming peer pressure and societal expectations [19], our study uniquely reveals how hope specifically enhances psychosexual health through improved future orientation and goal-directed thinking among Chinese adolescents.

With regard to self-efficacy, our findings build upon Rosenthal’s work by demonstrating its contribution to proactive attitudes toward sexual health education. Although their research focused primarily on behavioral outcomes [17], our study extends this understanding by demonstrating how self-efficacy contributes to broader psychosexual well-being, particularly in the context of Chinese cultural values and educational systems.

In terms of resilience, our results are consistent with Morsy and Yomna’s observations that resilient adolescents are better equipped to navigate the challenges associated with sexual development [21]. Our study advances this knowledge by identifying specific pathways through which resilience enhances psychosexual health, particularly in managing cultural pressures and maintaining positive sexual identity development within Chinese society.

Regarding optimism, our findings expand on the work of Thomson and Uribe, who emphasized the role of optimism in fostering personal strengths [24, 25]. While their research established the general benefits of optimism, our study specifically demonstrates its role in buffering against negative emotions and promoting informed decision-making in adolescent psychosexual development.

The significant moderating effect of autonomy in our findings can be interpreted through its dynamic interactions with each dimension of psychological capital. High autonomy amplifies the positive effect of hope by enabling adolescents to actively pursue their psychosexual health goals. Extending Brisson’s work [27], our study shows that autonomous adolescents are more capable of seeking relevant information and establishing boundaries aligned with their personal values. In terms of self-efficacy, autonomy empowers adolescents to negotiate safer practices and resist peer pressure [28]. Additionally, our findings demonstrate that autonomous adolescents are better able to leverage resilience by independently seeking support during periods of difficulty [31], and leverage optimism to make proactive, value-aligned decisions about their sexual health [32]. These findings extend the current understanding by demonstrating how autonomy strengthens the relationship between psychological capital and psychosexual health within Chinese cultural contexts, particularly through enhanced decision-making and health-seeking behaviors.

Contrary to our hypothesis, our findings revealed no significant moderating effect of gender on the relationship between psychological capital and psychosexual health. This unexpected result challenges traditional assumptions about gender differences in psychological resource utilization and sexual development. Previous studies like Closson and Lakomý suggested gender differences in psychological capital’s effects on mental health outcomes [35, 36]. However, our findings diminish gender gaps in psychological resource utilization among contemporary youth. Several factors may explain this non-significant moderation. First, evolving social norms and educational practices in China may have reduced traditional gender disparities in psychological resource access and utilization. Second, the universal nature of the beneficial effects of psychological capital may transcend gender-based differences, suggesting its fundamental role in adolescent development, regardless of gender identity. Additionally, improvements in sexual health education and mental health awareness in Chinese schools may have contributed to more equitable psychological resource development across genders. This finding contributes to the growing body of literature challenging gender-based assumptions in adolescent psychological development and suggests the need to focus on individual differences rather than gender-based interventions when promoting psychosexual health through psychological capital enhancement.

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to establish causal relationships between variables. Second, although we identified influential factors, the lack of intervention studies restricts the practical application of our findings.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to explore causal relationships between positive psychological capital and psychosexual health and conduct intervention studies to provide empirical support for promoting adolescent psychosexual health.

This study makes a valuable contribution to the existing literature by employing a quantitative methodological approach to examine the complex relationship between positive psychological capital and adolescent psychosexual health, while also exploring the moderating roles of autonomy and gender. This approach represents a departure from traditional research that has largely focused on the links between psychosexual health and negative mental health outcomes. The findings indicate that the key components of psychological capital—hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism—function as protective psychological resources that foster healthy psychosexual development in adolescents. Additionally, the moderating effects of autonomy and gender emphasize the importance of considering individual characteristics and contextual factors when investigating the mechanisms that support adolescent psychosexual well-being.

Based on these empirical findings, we strongly recommend the development and implementation of comprehensive psychological capital training programs specifically designed for adolescents and structured to enhance psychological well-being through targeted interventions that build hope, strengthen self-efficacy, develop resilience, and foster optimism. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies and the investigation of additional moderating variables, while the practical implications extend to informing evidence-based practices in adolescent health promotion, education, and counseling. This study not only fills a critical gap in the literature but also provides a foundation for shifting from a problem-focused approach to a strength-based perspective in addressing adolescent psychosexual health through the enhancement of psychological capital.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC) (Approval number is UM.TNC2/UMREC_3076). We obtained oral consent from the students, their parents or legal guardians, and the respective schools. For participants under the age of 16, we have obtained informed consent from the parent of any participant under the age of 16. We have ensured that our study adheres to ethical guidelines regarding minors’ participation. We have ensured that our study adheres to ethical guidelines regarding minors’ participation. The data collection process complied with local laws, regulations.

Not available.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Luo, J., Muhamad, H.B. & Chen, F. Positive psychological capital and adolescent psychosexual health: the moderating roles of gender and autonomy. BMC Psychol 13, 765 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03106-z