Nordic Nations Take Firm Stance on Ukraine Aid: No Joint Debt, Eyes on Frozen Russian Assets

Nordic leaders have unequivocally rejected the proposal of issuing common debt at the European Union level to finance a significant €140 billion reparations loan for Ukraine. Instead, they firmly assert that the necessary funds should be sourced from immobilised Russian assets rather than burdening national budgets. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen articulated this stance, stating, "I think, to be honest, it's the only way forward and I really like the idea that Russia pays for the damages they have they have done and committed in Ukraine." This position underscores a strong desire for Russia to bear the financial responsibility for its actions.

The project, commonly referred to as a "reparations loan," faced a significant hurdle last week when it was blocked by Belgium. Belgium holds the majority of the frozen assets belonging to the Russian Central Bank and raised a multitude of concerns, including the legal basis for such a move, the inherent risks of arbitration and confiscation, and the crucial need to ensure the participation and agreement of other G7 allies. This deadlock considerably softened the language of the recent summit's conclusions, which ultimately instructed the European Commission to explore options "as soon as possible" to address Ukraine's military and financial requirements for 2026 and 2027.

One potential option being considered, and one that has been utilised by the bloc previously for Kyiv albeit on a smaller scale, is the issuance of joint debt at the EU level to establish a programme of macro-financial assistance (MFA). While joint debt would circumvent the specific risks highlighted by Belgium regarding Russian assets, it would simultaneously increase the financial burden on member states. Many of these nations are already contending with challenges in controlling public spending and reassuring concerned investors, making this alternative a sensitive topic.

Despite the complexities, Nordic leaders remain resolute in their preference. Speaking at a Nordic Council meeting in Sweden, Prime Minister Frederiksen reiterated, "For me, there is no alternative to the reparations loan." She acknowledged the need to address some of the technical questions but stressed its fundamentally political nature. Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo echoed this sentiment, insisting that "the only reasonable solution is to use Russian frozen assets." Similarly, Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson hailed the summit's conclusions as a "major" and "necessary" step toward realising the reparations loan. The collective hope among the three Nordic leaders is that an agreement will be reached during the next meeting of the 27 EU leaders in December.

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, who participated in the Nordic meeting, carefully avoided the topic of joint debt. Instead, she staunchly defended her proposed plan, which involves utilising the cash balances from Russian assets to provide a loan to Ukraine, contingent on Russia eventually paying reparations. Von der Leyen described this as a "legally sound proposal, not trivial, but a sound proposal," indicating that the options the Commission will explore are intended to answer the "technical questions" surrounding the reparations loan. A spokesperson later clarified that while the exact scope of these options is still to be determined, the primary focus remains on Russian assets.

These recent remarks from Nordic capitals highlight a low appetite for incurring fresh EU-level debt, standing in direct contrast to the position articulated by Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever. De Wever has emerged as a significant obstacle in these discussions. Last week, he contended that Ukraine's Western allies possess sufficient wealth to absorb the costs independently, without needing to access Russian assets. He argued for the predictability of debt, stating, "The big advantage of debt is that you know it. You know how much it is, you know how long you will bear it, you know exactly who's responsible for it." Conversely, he underscored the considerable uncertainties associated with using Russian funds, including the unknown extent and duration of potential litigation and other unforeseen problems.

Member states, with Belgium at the forefront, are now awaiting the Commission's formal options paper. This document is expected to outline various alternatives, which could include direct loans and grants for Ukraine backed by the EU budget, national contributions, or a combination thereof. A potential strategy to sway De Wever and other hesitant parties involves incorporating sovereign assets located in other jurisdictions, such as France and Luxembourg, which hold smaller shares of frozen Russian funds. However, the fact that some of these funds are held in private banks presents another likely obstacle. The timeframe for reaching a definitive agreement is becoming increasingly tight, as Ukraine has indicated a critical need for a fresh injection of assistance in the second quarter of 2026.

You may also like...

President Alassane Ouattara set to begin his fourth consecutive tenure

President Ouattara on Monday, October 28 has been announced as the winner of the 2025 Ivorian Presidential election mark...

Platonic or Problematic: The Truth About Male–Female Friendships

Can a guy and a girl really just be friends, or is society too obsessed with turning every bond into a love story?

Egypt Reaffirms Its Diplomatic Clout in a Fragmented Region

Egypt is reclaiming its position in the middle of Arab and African diplomacy, one meeting at a time.

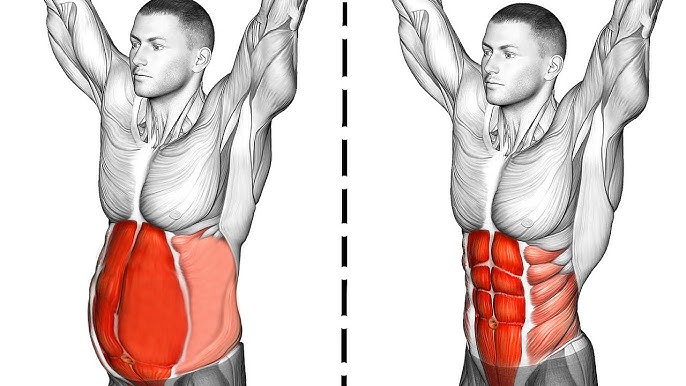

Abs Vs Belly: What do women Prefer

Some women love abs for their strength and discipline, but many admit a soft belly feels warmer, realer, and more inviti...

Forgotten at 80: Why the World Must Remember Aung San Suu Kyi, and Myanmar’s Broken Promise

Once the great hope for Myanmar, but now in jail. Aung San Suu Kyi marked her 80th birthday in Prison.

Plane Carrying 10 Foreign Tourists Crashes on its way to the Maasai Mara Reserve

A light plane crash in Kenya's coastal regions claimed 11 lives — 8 Hungarians, 2 Germans and a Kenyan Pilot in a fatal ...

Africa’s Image Economy: The Business of Looking Good

In Africa’s digital age, fashion has evolved from self-expression into a kind of survival. What began as cultural pride ...

Storm Alert: Hurricane Melissa Nears Usain Bolt's Home; Lyles & Coleman Rally Support For Jamaica

)

Hurricane Melissa, dubbed the "storm of the century," has made catastrophic landfall in Jamaica, bringing 185 mph winds,...