My Road Trip With the Velvet Sundown - The Atlantic

The traffic receded as Chicago withdrew into the distance behind me on Interstate 90. Barns and trees dotted the horizon. The speakers in my rental car, playing Spotify from my smartphone, put out the opening riff of a laid-back psychedelic-rock song. When the lyrics came, delivered in a folksy vibrato, they matched my mood: “Smoke in the sky / No peace found,” the band’s vocalist sang.

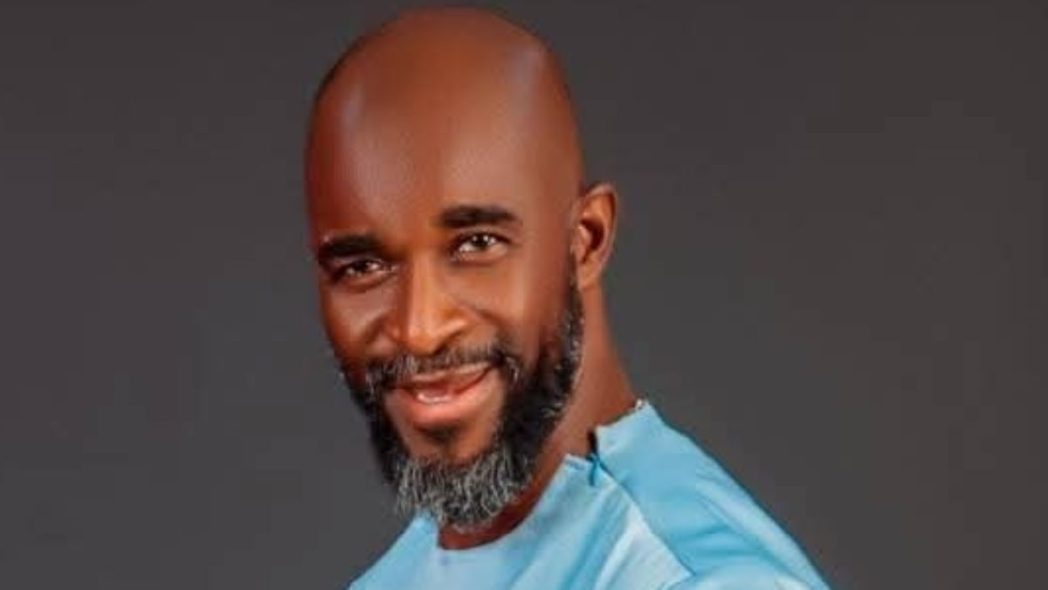

Except perhaps he didn’t really sing, because he doesn’t exist. By all appearances, neither does the band, called the Velvet Sundown. Its music, lyrics, and album art may be AI inventions. Same goes for the photos of the band. Social-media accounts associated with the band have been coy on the subject: “They said we’re not real. Maybe you aren’t either,” one Velvet Sundown post declares. (That account did not respond to a request for comment via direct message.) Whatever its provenance, the Velvet Sundown seems to be successful: It released two albums last month alone, with a third on its way. And with more than 850,000 monthly listeners on Spotify, its reach exceeds that of the late-’80s MTV staple Martika or the hard-bop jazz saxophonist Cannonball Adderley. As for the music: You know, it’s not bad.

It’s not good either. It’s more like nothing—not good or bad, aesthetically or morally. Having listened to both of the Velvet Sundown’s albums as I drove from Chicago to Madison, Wisconsin, earlier this week, I discovered that what may now be the most successful AI group on Spotify is merely, profoundly, and disturbingly innocuous. In that sense, it signifies the fate of music that is streamed online and then imbibed while one drives, cooks, cleans, works, exercises, or does any other prosaic act. Long before generative AI began its takeover of the internet, streaming music had turned anodyne—a vehicle for vibes, not for active listening. A single road trip with the Velvet Sundown was enough to prove this point: A major subset of the music that we listen to today might as well have been made by a machine.

The technical quilt that was necessary to produce an AI album has been assembling for some time. Large language models such as ChatGPT can produce plausible song lyrics, liner notes, and other textual material. Software such as Suno can, based on text prompts, create songs with both instrumentation and vocals. Image generators can be directed to create illustrated compositions for album art and realistic images of a band and its members, and then maintain the appearance of those people across multiple images. When I got to Madison, I signed up for Suno’s service. Mere moments later, I had created my own psychedelic-rock, road-trip-themed jam, a bit more amplified and less sitar-adjacent than the Velvet Sundown’s. I didn’t even have to name the track; Suno dubbed it “Endless Highway” on my behalf. “Rubber burns, the map fades away / Chasing the ghosts of yesterday,” its fake male vocalist intoned. Sure, fine.

But cultural circumstances have also made AI music tolerable, and even welcome to some listeners. At the turn of the century, Napster made digital music free, and the iPod made it legitimate. You could carry a whole record store in your pocket. Soon after, Spotify, which became the biggest music-streaming service, started curating and then algorithmically generating playlists, which gave listeners recommendations for new music and offered easy clicks into hours of sound in any subgenre, real or invented—acid jazz, holiday bossa nova, whatever. Even just the phrase lazy Sunday could be turned into a playlist. So could lawn mowing or baking. Whatever Spotify put into your queue was good enough, because you could always skip ahead or plug in a new prompt.

Real or not, the Velvet Sundown feels more like a playlist than a band. Its “Verified Artist” description on Spotify used to read, “Their sound mixes textures of ’70s psychedelic alt-rock and folk rock, yet it blends effortlessly with modern alt-pop and indie structures.” That assembly of influences, stretching across half a century, appears with greater and lesser prevalence in each of the band’s numbers. “As the Silence Falls” feels indie folk, with washed-out guitars and soft vocals; “Smoke and Silence” is more bluesy, with stronger vocals and a classic-rock feel. From track to track, the singer’s voice seems to change in tone too—perhaps a quirk of generativity—making the collection feel less like a purposeful LP and more like a blind-bag gamble.

Music used to define someone’s identity: punk, rock, country, alternative, and so forth. Asking “What music do you like?” could elicit a person’s taste, values, and fashion sense. The rockers might hang out behind the gym and smoke cigarettes; they were a clique just like the jocks and the nerds. Finding, joining, and deepening a connection to a music subculture required effort; you had to find the right venues, records, zines, or crowd. In that era, music was tribal. A relationship with the Sisters of Mercy, Guns N’ Roses, or Bauhaus represented a commitment.

Not so much today. The internet has fragmented and flattened subcultures. The Velvet Sundown’s puppeteers present the band’s soft pastiche of genres—psychedelic, folk, indie—as sophisticated fusion, but of course it’s nothing more than a careless smear of stylistic averages. Psychedelic, folk, and indie rock each in their own way have something to say, musically and lyrically—about musical convention, spirituality, introspection, or social and political circumstances. The Velvet Sundown doesn’t seem to care about any of those things.

This approach appears to be serving the band or its creators very well. The Velvet Sundown may actually appeal to people. None of its tracks go hard; instead, each one offers something slightly different—a sitar lick, a blues-guitar solo, a folk-adjacent country twang—that might prove palatable to any given listener. Perhaps no human artist could tolerate producing such soulless lackluster, but an AI is unburdened by shame.

The lyrics’ milquetoast moodiness may also contribute to the band’s listener numbers. Each line is short, and the phrases barely connect to one another, making it easy for listeners to hear whatever they might want to hear: “Dust on the wind / Boots on the ground / Smoke in the sky / No peace found.” Really makes you think, until you realize that, no, it doesn’t at all. Where the music engages with the political commitments that often characterize its influences, it does so in a way that could mean anything. Take the chorus of “End the Pain,” one of the band’s top songs on Spotify. Singing with folk-rock urgency, the alleged “frontman and mellowtron sorcerer” Gabe Farrow pleads, “No more guns, no more graves / Send no heroes, just the brave.” These words convey the sensibility of an anti-war anthem, but they offer so little detail that the song could adequately service supporters or detractors of any conflict, past or present.

Anonymous and mild sensibilities have currency because today’s music—whether created and curated by humans or machines—is so often used to make people feel nothing instead of something. In open-plan offices, people started donning headphones to gain some semblance of privacy. At home, they do the same to mask the sound of traffic or their roommates’ Zoom calls. Internet-connected, whole-house audio systems can turn any room into a souped-up, algorithmic white-noise machine that sounds like Italo disco or chillhop in the way that LaCroix tastes like lime. The music that is best adapted for these settings is that which descends from what Brian Eno dubbed, on his 1979 album, Music for Airports, “ambient.” This music is not meant to be listened to directly; it’s used to drown out everything else.

As I drove amid the cornfields on I-90, the Velvet Sundown did just that. The band’s tracks were not satisfying in any way, but they were apt. I was on the road, but I could be anywhere—awaiting a Pilates class, paying for deli meat, scrolling through internet memes—and the sound would hit the mark.

And the worst part was that it was fine. It was fine! To my great embarrassment, the Velvet Sundown’s songs even managed to worm their way into my brain. Did I like their music? No, but my aesthetic judgment had given over to its vibes, that contemporary euphemism for ultra-processed atmosphere.

How far could I push this feeling? Returning to the car after a refreshment stop, I tried to make Spotify go meta on the band: I asked the app to generate a playlist made from songs that are similar to the Velvet Sundown’s. A list appeared of bands I didn’t recognize. Many seemed a little off: Appalachian White Lightning and Flaherty Brotherhood sounded like they might be AI acts as well. (A little Googling revealed that others suspect the same.) I suppose this makes sense; I was asking the algorithm to give me a channel of sanitized, inauthentic-seeming psychedelic-folk-indie rock, and it delivered. I pondered for a moment whether any of the other artists on my custom playlist (the South Carolina folk-rock singer-songwriter Johnny Delaware? The Belgian folk-pop quartet Lemon Straw?) might be fake—and how one might try to suss that out.

The question felt exhausting, so I switched back to the Velvet Sundown. As I drove and the music played, I felt nothing—but I felt that nothing with increasing acuteness. I was neither moved nor sad nor pensive, just aware of the fact that my body and mind exist in a tenuous zizz somewhere between life, death, and computers. This is second-order music listening, in which you experience the idea of listening to music. What better band to provide that service than one that doesn’t even exist?

But looking toward the blushing sky ahead of me, I realized that I didn’t even want this music to be art, or to feel that I was communing with its makers. I simply hoped to think and feel as little as possible while piloting my big car through the empty evening of America. This music—perhaps most music now—is not for dancing or even for airports; it’s for the void. I pressed play and gripped the wheel and accelerated back onto the tollway, as the machines lulled me into oblivion.