BMC Health Services Research volume 25, Article number: 931 (2025) Cite this article

This study examines the attitudes of medical students in the Al-Jouf region of Saudi Arabia and their potential influence on future healthcare delivery for people with intellectual disabilities (PwIDs). The research focuses on three fundamental concepts-ethical attitudes (EA), professional attitudes (PA), and social attitudes (SA)-to evaluate their direct role in determining healthcare quality. Furthermore, the study investigates the mediating functions of Knowledge Acquisition (KA) and Communication Skills (ComS). To assess the relationships between variables in a sample of 166 medical students, data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, hypothesis testing, and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The analysis suggests associations between medical students’ ethical, professional, and social attitudes and their potential approaches to future healthcare delivery for PwIDs. Knowledge Acquisition emerged as a significant mediating factor, while Communication Skills showed no significant mediating effect, possibly reflecting curricular gaps in communication training. These findings suggest several specific interventions: (1) integration of structured PwIDs-focused modules within medical curricula, emphasizing both theoretical knowledge and practical skills; (2) implementation of mandatory clinical rotations with PwIDs populations to enhance experiential learning; and (3) development of communication training programs focusing on patient-doctor and interprofessional interactions. The study suggests that policymakers and medical educators should set clear standards for disability skills in medical training, create ways to evaluate how well students care for PwIDs, and develop specific training programs for teachers.

Enhancing the quality of healthcare services for PwIDs constitutes a pervasive global issue, as this demographic frequently encounters profound disparities in healthcare access. Not having enough proper care, misdiagnosing conditions, and biased views from healthcare workers make these inequalities worse [1, 31, 43, 50]. Medical students’ attitudes during their educational journey are pivotal in shaping their future approach to healthcare delivery for PwIDs. The beliefs that medical students cultivate throughout their educational experience can reinforce these disparities or mitigate the healthcare divide faced by this at-risk population. Understanding the impact of medical students’ attitudes on healthcare quality is essential for fostering more inclusive healthcare settings.

In the Al-Jouf province of Saudi Arabia, a predominantly conservative region in the north of the country with unique cultural traditions and family structures, there is a significant opportunity to enhance health outcomes for PwIDs by reshaping medical students’ perceptions and educational training. Empirical evidence suggests that the beliefs and attitudes of medical students profoundly affect their clinical practices and patient interactions [6]. The region’s traditional healthcare delivery system, combined with strong family-centered care practices, presents both challenges and opportunities in care for PwIDs [2]. While family support networks are robust, cultural stigma and limited professional training in care for PwIDs remain significant barriers. Despite the existence of biases influenced by medical students’ educational backgrounds, these biases can be addressed through educational programs that promote empathy, comprehension, and a heightened awareness about PwIDs [47]. Research suggests that changing these attitudes can lead to more compassionate care, which in turn improves patient satisfaction and health outcomes [1, 3, 18].

Current research has extensively documented healthcare practitioners’ attitudes and their impact on care quality in Western contexts. However, significant gaps exist in understanding how these attitudes develop within medical education systems in culturally distinct regions like Al-Jouf. Many investigations have examined the influence of healthcare practitioners’ attitudes on the provision of patient care, yielding significant evidence that affirmative attitudes correlate with improved care outcomes [11, 22, 24, 30, 40]. However, there is a need for more research concerning the formation of these attitudes among medical students within specific cultural and educational frameworks, such as Al-Jouf. Specifically, limited research exists on how regional cultural values and educational practices influence the development of medical students’ attitudes toward PwIDs care, particularly in conservative societies where family structures play a central role in healthcare delivery.

The primary objectives of this study are to:

Medical students’ attitudes toward PwIDs can significantly influence their future approach to healthcare delivery. These developing attitudes during medical training are pivotal in shaping their future provision of care, understanding of service availability, and potential impact on health outcomes and comprehensive health results. It is important to note that negative attitudes, including stigma and misconceptions, can lead to a phenomenon known as diagnostic overshadowing, where healthcare providers incorrectly attribute symptoms to the disability itself rather than investigating them as separate health issues [50]. The cultural context in which healthcare is provided also shapes these attitudes, resulting in variations in the quality of care across different regions. For instance, Courtenay et al. [9] noted that differences in deinstitutionalization processes and professional training across Europe have led to disparities in healthcare quality for PwIDs. As healthcare professionals, you have the power to shape these attitudes and improve the quality of care for PwIDs.

The self-efficacy and preparedness of healthcare providers, particularly the trainees, are critical factors in improving care for PwIDs. A study conducted in Ghana revealed that healthcare students exhibited ambivalence in their attitudes and self-confidence when caring for PwIDs, highlighting the need for curriculum reforms to address these issues [32, 33]. To meet the complex needs of PwIDs and reduce health disparities, integrated care models that coordinate services across different providers are essential. These models ensure that PwIDs receive comprehensive care tailored to their unique needs [7]. Furthermore, it was shown that comprehensive training in disability competency fosters positive attitudes, enhances provider confidence, and improves patient experiences [16].

Education and exposure to PwIDs were identified as powerful tools for improving healthcare delivery by fostering positive attitudes. Werner and Stawski [52] found that clinicians who received training on intellectual disabilities demonstrated increased empathy and investment in patient care. These findings highlight the potential for positive change in healthcare delivery and underscore the importance of educational interventions in shaping healthcare providers’ attitudes and improving the quality of care for PwIDs. By implementing targeted education programs and integrated care models, healthcare systems can promote equity and inclusion, ultimately enhancing this vulnerable population’s healthcare experience and outcomes. Additionally, attitudes also influence provider behaviors related to healthy lifestyle promotion, including nutrition and preventive care [34].

Research has identified three key attitudinal dimensions affecting healthcare delivery for PwIDs:

Ethical attitudes

Ethical attitudes are fundamental to healthcare access for PwIDs, with evidence showing systemic issues in justice and autonomy [37]. Educational interventions can improve medical students’ ethical understanding, though challenges persist in informed consent comprehension [17, 25, 46]. While teaching outcomes vary [48], nurse-led training has shown promise in enhancing patient care understanding [35].

Professional attitudes

Professional attitudes directly influence care quality through their impact on healthcare delivery and patient experiences. Research demonstrates that targeted educational programs enhance professional preparedness [11, 27], though studies in Ghana indicate ongoing challenges in professional attitude development [32, 33]. Positive professional attitudes, particularly among those working closely with PwID, correlate with improved support quality [22, 48]. These attitudes contribute significantly to patient self-acceptance and overall well-being [42, 49].

Social attitudes

Social attitudes significantly shape healthcare quality through their influence on clinical interactions. Studies demonstrate that varied attitudes among healthcare students can create care disparities [21, 36]. Educational exposure can improve these attitudes [5], though both explicit and implicit biases require attention through targeted interventions [4, 8, 12, 54].

Research indicates that both knowledge acquisition and communication skills may mediate the relationship between healthcare provider attitudes and care quality for PwIDs. Knowledge acquisition has emerged as a critical component, with systematic reviews demonstrating its impact on clinical performance. Imanipour et al. [19] found that competency-based education significantly improves healthcare delivery outcomes, while Rotenberg et al. [39] showed that structured knowledge acquisition enhances both provider competence and patient outcomes. Vicente et al. [51] specifically linked provider knowledge to improved patient self-determination and autonomy in PwID care. DeBeaudrap et al. [10] further demonstrated how knowledge levels affect providers’ ability to address systemic barriers to care access.

Communication skills similarly play a vital mediating role, though through different pathways. Drossman et al. [13] documented how effective provider-patient communication enhances treatment adherence and outcomes, while Vicente et al. [51] showed its influence on patients’ informed decision-making abilities. Kerr et al. [20] found that enhanced communication skills improve providers’ ability to address complex patient needs. The potential negative impacts of poor communication were highlighted by Miranda et al. [27], who identified increased stress levels among patients and caregivers, while Williams et al. [53] demonstrated how inclusive communication strategies improve healthcare participation. Kwame and Petrucka [23] further supported communication’s mediating role through their analysis of nurse-patient interactions and healthcare outcomes.

This synthesized evidence suggests that both knowledge acquisition and communication skills may serve as important mediating pathways between healthcare provider attitudes and care quality for PwIDs, albeit through distinct mechanisms.

Despite extensive literature on healthcare attitudes in Western contexts, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the development of attitudes within culturally distinct medical education systems. This issue is particularly evident in regions like Al-Jouf, where traditional family-centered care practices influence healthcare delivery. The present study seeks to address this gap by examining three critical research questions:

This investigation contributes to existing literature by examining attitude formation within a unique cultural context, providing insights for medical education reform and policy development aimed at reducing healthcare disparities for PwIDs.

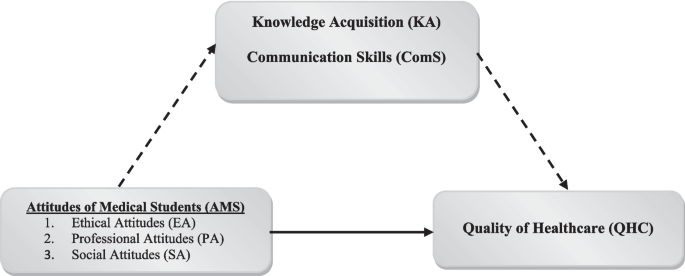

This study’s framework examines the relationships between medical students’ current attitudes and their potential impact on future healthcare delivery (Fig. 1). Unlike previous studies, this research specifically focuses on medical students during their training period, rather than practicing healthcare providers. The framework investigates how medical students’ current attitudes-categorized into EA, PA, and SA-may influence their approach to future healthcare delivery for PwIDs. Additionally, the framework explores how KA and ComS may mediate these relationships during the educational process.

Research framework. The direct pathway through which attitudes of AMS affect the QHC is indicated with a solid arrow. The indirect pathway, where KA and ComS mediate the effects AMS on QHC, is shown with dashed arrows

Based on the reviewed literature examining healthcare attitudes toward PwIDs and the research framework illustrated in Fig. 1- which depicts both direct and indirect pathways between medical students’ attitudes and healthcare quality- this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Direct Effects Hypotheses

H1: Medical Students’ Attitudes influence Healthcare Quality in the Al-Jouf Region (represented by the solid arrow in Fig. 1).

Mediating Effects Hypotheses (represented by dashed arrows in Fig. 1).

Knowledge Acquisition Mediation

H2: Knowledge Acquisition mediates the relationship between Medical Students’ Attitudes and Healthcare Quality.

Communication Skills Mediation

H3: Communication Skills mediate the relationship between Medical Students’ Attitudes and Healthcare Quality.

This cross-sectional study employed structural equation modeling to examine the relationships between medical students’ attitudes and healthcare quality for PwIDs at the College of Medicine, Al-Jouf University, from June to September 2024. The sample size was determined using power analysis for PLS-SEM, with a minimum requirement of 147 participants to detect medium effects (f2 = 0.15) at 80% power with up to six predictors.

The study sample comprised 166 medical students from the College of Medicine et al.-Jouf University (total student population: 504). Data collection occurred between June and September 2024, coinciding with a period of reduced academic commitments to maximize participation opportunities. Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of the participants’ demographic characteristics.

The sampling process combined convenience and stratified random sampling techniques to ensure representative participation. Initially, convenience sampling facilitated preliminary recruitment of willing participants. This was followed by stratified random sampling that categorized participants based on gender, age, academic year, and prior experience with PwIDs. Random sampling within each subgroup further enhanced diversity and ensured a representative sample of the broader student body.

To enhance inclusivity and reduce selection bias, the study implemented targeted outreach initiatives and offered the survey in Arabic with alternative format options for improved accessibility. The study received ethical approval from the National Committee of Scientific Research (NCSR) et al.-Jouf University (Approval No. 02–09–46). All participants provided informed consent after receiving comprehensive information about the study purpose, confidentiality measures, and the voluntary nature of their participation.

The study utilized an Arabic-language questionnaire developed specifically for assessing medical students’ attitudes toward healthcare for PwIDs. The questionnaire included two main sections: demographic data collection and attitude assessment. The attitude assessment section comprised 25 validated items categorized into six principal constructs: EA, PA, SA, KA, ComS, and QHC. An English version of the questionnaire is available in Appendix 1.

The measurement instruments were adapted from established research in healthcare and education fields. The attitude constructs (EA, PA, and SA) were measured using 12 items adapted from Reto et al. [37], Siegel et al. [46], McDonald & Kidney [25], Iacono & Carling-Jenkins [17], and Patel et al. [35]. The Quality of Healthcare (QHC) construct used five items from Van den Bemd et al. [50], Courtenay et al. [9], and Opoku et al. [32, 33]. The mediating constructs-Knowledge Acquisition and Communication Skills-were assessed through eight items adapted from Debeaudrap et al. [10], Williams et al. [53], and Vicente et al. [51].

The questionnaire underwent rigorous development and validation. Initial English-language items were translated into Arabic using a forward–backward translation process involving two independent translators. The instrument was pilot-tested with 30 medical students to assess clarity and cultural appropriateness. Reliability analysis showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.80) for all constructs. Validity was established through expert review and confirmatory factor analysis.

Data analysis followed a systematic approach. The initial data screening included assessment of missing values, outliers, and normality assumptions. PLS-SEM analysis was conducted using SmartPLS software, following a two-step process: (1) evaluation of the measurement model through reliability and validity assessments, and (2) structural model testing using bootstrapping procedures (5000 resamples) to facilitate hypothesis testing.

PLS-SEM was selected as the primary analytical method due to several key considerations [44]. First, the method’s capability to handle complex relationships between multiple constructs simultaneously made it particularly suitable for examining the mediating roles of KA and ComS. Second, PLS-SEM’s robustness in analyzing non-normally distributed data and smaller sample sizes aligned well with the study’s regional scope and sample characteristics. Additionally, its predictive modeling capabilities were especially relevant for exploring the relationships between attitudinal constructs and potential healthcare outcomes in an educational context.

Given the self-reported nature of the data, several measures were implemented to enhance their quality and reliability. These included: (1) anonymous response collection to encourage honest reporting, (2) pilot testing of the questionnaire with a small student group to ensure clarity and minimize misinterpretation, (3) incorporation of reverse-coded items to detect response patterns, and (4) implementation of multiple validation checks during data collection. Despite these measures, the limitations inherent to self-reported data were considered in the analysis and interpretation of the results.

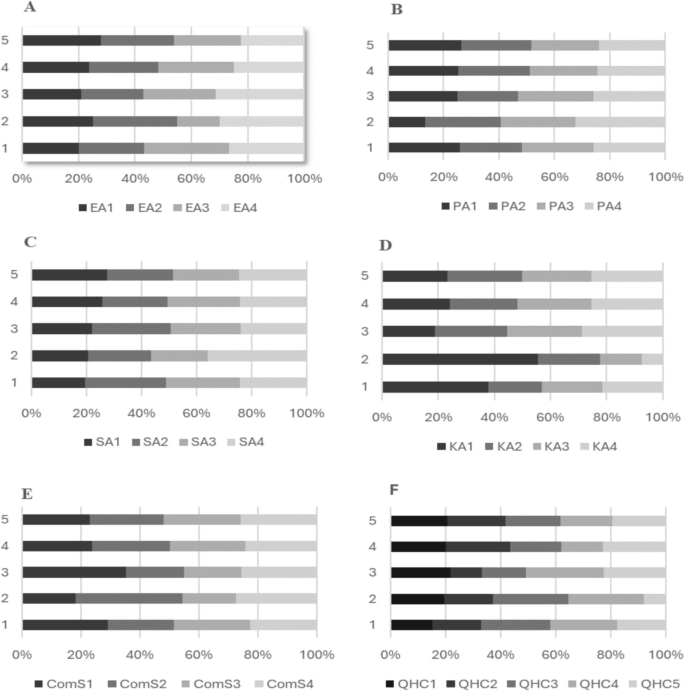

Table 2 reports the means and standard deviations of responses to each questionnaire subconstruct. The Communication Skills subconstruct received the highest average rating, with a mean score of 4.12 and a standard deviation of 0.95, indicating a strong confidence in healthcare communication practices for PwIDs. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of Likert-type responses across the questionnaire items.

Distributions of questionnaire responses. The precise number of Likert responses (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) for each item are indicated within curly brackets herein. (A‒F) AMS variables: (A) EA items: {EA1: 6, 5, 18, 59, 78}, {EA2: 7, 6, 19, 61, 73}, {EA3: 9, 3, 22, 66, 66}, {EA4: 8, 6, 27, 62, 63}; (B) PA items: {PA1: 8, 5, 25, 65, 63}, {PA2: 7, 5, 24, 63, 67}, {PA3: 6, 8, 23, 68, 61}, {PA4: 5, 7, 21, 71, 62}; (C) SA items: {SA1: 6, 7, 26, 64, 63}, {SA2: 8, 5, 20, 66, 67}, {SA3: 7, 9, 22, 67, 61}, {SA4: 9, 6, 25, 60, 66}; (D) KA items: {KA1: 7, 6, 19, 66, 68}, {KA2: 6, 8, 22, 64, 66}, {KA3: 8, 4, 25, 63, 66}, {KA4: 5, 7, 27, 62, 65}; (E) ComS items: {ComS1: 6, 7, 20, 65, 68}, {ComS2: 7, 5, 23, 66, 65}, {ComS3: 5, 9, 22, 63, 67}, {ComS4: 6, 6, 26, 64, 64}; (F) QHC items: {QHC1: 6, 4, 24, 65, 67}, {QHC2: 7, 6, 23, 63, 67}, {QHC3: 8, 5, 21, 66, 66}, {QHC4: 7, 7, 26, 62, 64}, {QHC5: 5, 6, 22, 67, 66}

Medical students’ Ethical Attitudes recorded a mean score of 4.09 (SD = 0.96), indicating favorable dispositions toward future ethical considerations in healthcare delivery for PwIDs. The mean scores for PA and SA were measured at 3.95 (SD = 0.62) and 3.89 (SD = 0.79), respectively, showing a significant connection with these themes. The average KA score was 3.98 (SD = 0.71), reflecting a predominantly positive perception regarding knowledge of intellectual disabilities However, Quality of Healthcare (QHC) recorded the lowest average score of 3.81 (SD = 0.70) among the assessed constructs, suggesting areas where healthcare quality can be further enhanced.

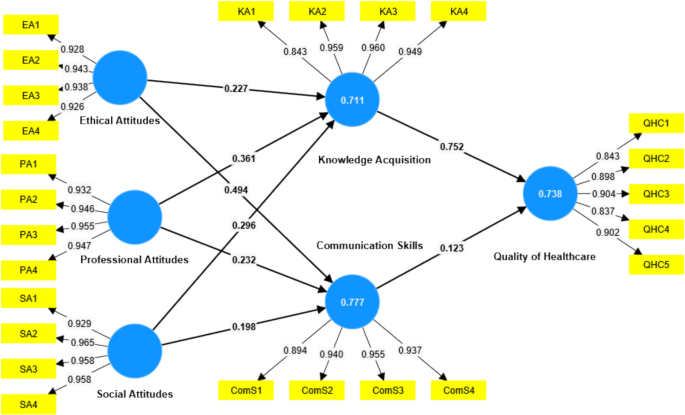

Figure 3 presents the measurement Model used in the structural equation modeling analysis. This model serves as both a theoretical framework and a practical tool for exploring medical students’ attitudes and their impact on healthcare quality. The model features latent constructs such as EA, PA, SA, KA, ComS, and QHC, each linked to observed indicators (e.g., EA1 to EA4). The model highlights the loadings, which indicate the strength of relationships between each construct and its indicators, and correlation coefficients between different constructs.

Measurement Model. The numerical values show factor loadings for each construct (yellow boxes), with solid lines indicating direct relationships and standardized path coefficients between attitudes (EA, PA, SA), mediating factors (KA, ComS), and healthcare quality. Higher values (closer to 1.0) represent stronger relationships between variables

Table 3 shows that the measurement model meets the reliability and validity criteria outlined by Sarstedt, Ringle, and Hair [38, 45]. The factor loadings for all items exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70. For instance, the EA construct, with loadings ranging from 0.926 to 0.943, highlights high consistency between the items and the construct. The VIF values, which measure multicollinearity, all fall below the acceptable limit of 5, as recommended by Hair et al. [15]. For instance, the VIF values for PA range between 3.203 and 4.526, further supporting the distinctiveness of the items.

In terms of internal consistency, both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability exceed the minimum threshold of 0.70 for all constructs, confirming the high reliability of the model. For instance, Social Attitudes has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.966 and composite reliability of 0.975, indicating that the items within this construct are highly consistent in measuring the same underlying dimension. Similarly, the other constructs, such as Knowledge Acquisition and Communication Skills, also display high reliability, with composite reliability values of 0.962 and 0.964, respectively.

Convergent validity, as indicated by the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), is also confirmed across all constructs, with values well above the threshold of 0.50. The AVE values, ranging from 0.770 for Quality of Healthcare to 0.908 for Social Attitudes, show that the constructs explain a substantial portion of the variance in their respective indicators.

It is very important to make sure that each part of the model is different from the others using the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which is an important method for testing discriminant validity. Sarstedt et al. [45] say that the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs should be higher than the correlation between that construct and any other constructs in the model. In Table 4, the bold diagonal values represent the square root of the AVE for each construct, and they are all greater than the corresponding off-diagonal values in their respective rows and columns. For example, the square root of the AVE for communication skills is 0.932, and its correlation with EA is 0.857, which is lower than the AVE value. This pattern holds across all constructs, such as EA, with an AVE of 0.934, which is more significant than its correlations with other constructs. Hence, according to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the measurement model exhibits favorable discriminant validity. The heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) provides another robust method for assessing discriminant validity. This analysis, as recommended by Hair et al. [15], confirms that HTMT values below 0.85 indicate discriminant validity. In our study, the HTMT values for all constructs are within this acceptable range, with the highest value being 0.821 between SA and PA. Despite being close to the threshold, this value still indicates an acceptable level of discriminant validity. Most HTMT values are significantly lower, such as the HTMT ratio of 0.701 between ComS and EA, which falls well within the acceptable range. These HTMT analysis results confirm that the constructs are not overly correlated and that the model exhibits adequate discriminant validity.

Table 5 delineates the structural model fit. It reveals high R-squared and adjusted R-squared metrics for Communication Skills (0.777 and 0.775) and Knowledge Acquisition (0.711 and 0.708), which meet the recommended threshold of 0.75 as suggested by Sarstedt et al. [45] and Hair et al. [14]. The Quality of Healthcare model has an R-squared value of 0.738, which is slightly below the recommended threshold. This indicates that while the model has solid predictive capabilities in most areas, there is still room for improvement in explaining the results. Table 3 shows that the measurement model demonstrates robust reliability and validity, adhering to the criteria outlined by Sarstedt, Ringle, and Hair [45]. The large amount of variance explained further supports the model’s robustness, proving that the attitudes of medical students, along with the mediating variables, effectively explain the differences in healthcare quality, communication skills, and knowledge acquisition in this situation.

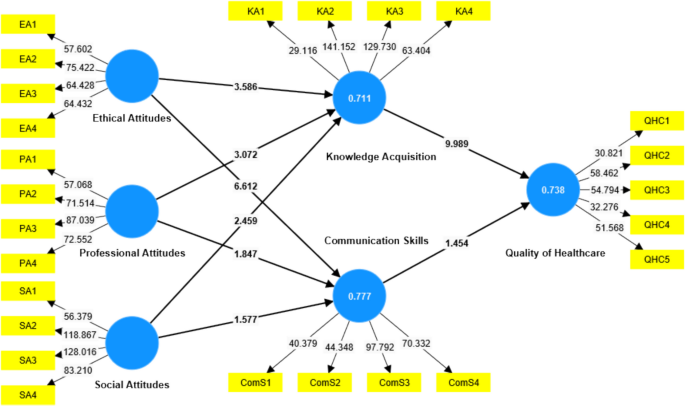

Figure 4 displays the structural model and the t-values from bootstrapping (5000 resamples), showing how significant the links are between attitudes, mediators, and healthcare quality. Table 6 presents the results of the hypothesis testing, shedding light on the correlation between the attitudes of medical students and the quality of healthcare provided to intellectually disabled patients. The direct relationships between EA, PA, and SA with QHC were all found to be significant. A standardized beta of 0.232 and a t-value of 3.994 (p = 0.000) specifically supported H1a (EA-> QHC), indicating that ethical attitudes positively influence healthcare quality. This suggests that interventions aimed at improving ethical attitudes among medical students could lead to better healthcare for PwIDs. Similarly, H1b (PA-> QHC) revealed a significant positive relationship, with a beta of 0.300 and a t-value of 3.097 (p = 0.002). Professional attitudes are key contributors to improving healthcare quality, implying that training programs focusing on professional attitudes could enhance healthcare provision. Finally, we found support for H1c (SA-> QHC), albeit with a slightly lower beta of 0.247 and a t-value of 2.341 (p = 0.019). While this effect is weaker, it still indicates that social attitudes positively influence healthcare quality, suggesting that promoting positive social attitudes could also improve healthcare for PwIDs.

Structural Model (Bootstrapping @5000). The model shows t-values from bootstrap analysis, indicating statistical significance of relationships between attitudes (EA, PA, SA), mediating factors (KA, ComS), and QHC. Values above 1.96 indicate significant pathways at p < 0.05 level

Strong evidence supports the role of knowledge acquisition as a mediator between attitudes and healthcare quality, highlighting the significance of continuous learning in healthcare. H2a (EA‑> KA-> QHC) was accepted with a beta of 0.171 and a t-value of 3.229 (p = 0.001), suggesting that knowledge acquisition significantly enhances the effect of ethical attitudes on healthcare quality. Similarly, H2b (PA-> KA-> QHC) was found to be significant, with a beta of 0.272 and a t-value of 2.938 (p = 0.003), confirming that knowledge acquisition mediates the relationship between professional attitudes and healthcare quality. Additionally, H2c (SA-> KA-> QHC) was supported with a beta of 0.222 and a t-value of 2.303 (p = 0.021), indicating that knowledge acquisition also mediates the impact of social attitudes on healthcare quality.

In contrast, the mediating role of Communication Skills did not yield significant results, highlighting the need for further research in this area. H3a (EA-> ComS-> QHC) was rejected, with a beta of 0.061 and a t-value of 1.397 (p = 0.163), as the confidence interval crossed zero. Likewise, H3b (PA-> ComS-> QHC) and H3c (SA-> ComS-> QHC) were also rejected, with respective beta values of 0.029 and 0.024 and t-values of 1.150 and 0.938. The p-values were above the 0.05 threshold in both cases, and the confidence intervals confirmed no significant mediation effect.

In conclusion, the analysis reveals that ethical attitudes, professional attitudes, and social attitudes significantly influence the standard of healthcare. More importantly, knowledge acquisition is not just a factor but a critical mediator, amplifying the positive impacts of medical students’ attitudes on healthcare quality. This underscores the paramount importance of continuous learning and knowledge acquisition in healthcare. It is not just a part of the process; it is a crucial element. Importantly, Communication Skills did not emerge as a significant mediating variable, highlighting the need to focus on other factors that contribute to healthcare quality.

The cross-sectional analysis examines the relationship between medical students’ attitudes during training and their perspectives on future healthcare delivery for PwIDs. While previous research has established correlations between healthcare providers’ attitudes and patient experiences [30, 43], this study focuses specifically on educational experiences and their potential influence on future practitioners’ approaches. Research indicates that negative attitudes, often rooted in stigma and misconceptions, correlate with healthcare inequalities for PwIDs, including diagnostic challenges, care quality, and patient autonomy [26]. The current findings suggest that positive attitudes, particularly in ethical and professional domains, may contribute to enhanced healthcare delivery. These observations support the potential value of targeted education and exposure in developing healthcare professionals’ competencies, aligning with previous research on inclusive care approaches for PwIDs [29, 40, 41]. One critical challenge identified in healthcare delivery for PwIDs is ‘diagnostic overshadowing’. This phenomenon describes situations where healthcare professionals attribute symptoms to the intellectual disability rather than recognizing them as separate health issues, potentially contributing to underdiagnosis and undertreatment. The research suggests that addressing this challenge during medical training may help develop more comprehensive diagnostic approaches.

The findings suggest the value of addressing potential biases through enhanced educational approaches and skill development during medical training. Research by Ambrose et al. [7] indicates that integrated care models, combined with comprehensive training in disability competency [16], show promising associations with healthcare outcomes for PwIDs. Courtenay et al. [9] observed regional variations in care quality that correspond with differences in training approaches and attitudes, suggesting potential benefits from standardized curriculum development.

The analysis supports a significant correlation between Ethical Attitudes and students’ perspectives on healthcare delivery. Literature review reveals persistent systemic challenges, including reports of dehumanized treatment and limited patient autonomy in healthcare settings [37]. These observations underscore the importance of examining how educational interventions might address such ethical concerns.

Research suggests associations between educational interventions and enhanced ethical engagement and patient autonomy considerations [25, 46]. The data analysis indicates correlations between Professional Attitudes and students’ perspectives on healthcare delivery. Studies have observed relationships between professional attitudes and care delivery patterns [11, 27]. Previous research suggests that training, experience, and exposure may contribute to the development of professional attitudes, particularly regarding care for vulnerable populations [42, 49].

The analysis also revealed significant correlations between social attitudes and students’ approaches to healthcare delivery, aligning with previous research that examined relationships between healthcare students’ attitudes and care disparities [21, 36]. Studies have observed associations between educational exposure and reduced stigma toward intellectual disabilities [5]. Indeed, research has indicated relationships between both explicit and implicit attitudes and healthcare providers’ approaches to treating PwIDs, suggesting potential benefits from targeted educational interventions and policy development [8, 12, 28, 54].

The analysis demonstrates Knowledge Acquisition as a significant mediator between medical students’ attitudes and their potential future healthcare delivery for PwIDs. Vicente et al. [51] and Debeaudrap et al. [10] support this finding, showing how targeted knowledge enhances patient autonomy and addresses systemic barriers to healthcare access.

In contrast, Communication Skills did not emerge as a significant mediator, despite its documented importance in healthcare literature. While Vicente et al. [51] and Williams et al. [53] highlight how effective communication enhances patient outcomes and life quality, the Al-Jouf region’s distinct healthcare system may explain this finding. The region’s hierarchical professional relationships and family-mediated communication patterns, combined with limited intellectual disability-specific training, create a unique context where traditional communication roles prevail.

To address these regional specificities, practical interventions could include specialized intellectual disability communication modules incorporating role-playing exercises and local case studies. Structured clinical rotations and region-specific communication protocols could help balance family involvement with direct patient communication while maintaining cultural appropriateness.

While this study did not find significant support for the role of communication skills, the broader literature suggests that improving communication is essential for better healthcare outcomes. For example, Miranda et al. [27] demonstrated that ineffective communication can exacerbate existing challenges and increase caregiver stress. Therefore, despite this study’s lack of significant results, it is our collective responsibility to promote strong communication skills among healthcare providers.

This study explored the relationship between medical students’ attitudes in the Al-Jouf region and the quality of healthcare provided to PwIDs. Our study identified correlations between medical students’ ethical, professional, and social attitudes and their perspectives on healthcare delivery for PwIDs. While these attitudes may shape future practice, longitudinal research would be needed to establish causal relationships between current attitudes and eventual healthcare quality outcomes. This study provides insights into how medical education might influence future healthcare delivery, while acknowledging that actual healthcare quality outcomes were not directly measured. Students exhibiting these positive attitudes were more inclined to deliver superior care, aligning with existing literature. Knowledge Acquisition emerged as a mediator between attitudes and health outcomes, highlighting the urgency and necessity of specialized education and training in advancing care for PwIDs.

Interestingly, despite extensive literature supporting the importance of communication skills in healthcare quality, this study did not find them to be a significant mediator. This result may reflect regional differences in the emphasis on communication within medical education or limited student exposure to direct interactions with PwIDs. These results highlight the imperative for educators and policymakers in the Al-Jouf region to emphasize the development of affirmative attitudes and to equip students with the requisite knowledge and skills necessary for the care of PwIDs. By doing so, they can strive to enhance healthcare equity for this demographic.

Our findings relied on data reported by participants themselves, which could be influenced by a desire to appear favorable, thus encouraging students to express more optimistic views than they genuinely have. Subsequent research endeavors might rectify this limitation by utilizing observational methodologies or qualitative interviews to understand better students’ attitudes and behaviors within authentic clinical environments.

Additionally, the lack of a significant mediating effect of Communication Skills suggests a need to explore this area further. Future research endeavors should examine the significance of communication training in medical education and consider the cultural variables that affect the emphasis on communication within healthcare settings. Analyzing additional potential mediators, including constructs such as empathy or emotional intelligence, may yield a more thorough comprehension of the relationship between medical students’ attitudes and their capacity to deliver high-quality care to PwIDs.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- PwIDs:

-

People with Intellectual Disabilities

- EA:

-

Ethical Attitudes

- PA:

-

Professional Attitudes

- SA:

-

Social Attitudes

- KA:

-

Knowledge Acquisition

- ComS:

-

Communication Skills

- QHC:

-

Quality of Healthcare

- PLS-SEM:

-

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling

- NCSR:

-

National Committee of Scientific Research

- AMS:

-

Attitudes of Medical Students

- AVE:

-

Average Variance Extracted

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- HTMT:

-

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No (DSR2023-04-02183).

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jo Al-Jouf University under grant No (DSR2023-04–02183).

This study received ethical approval from the National Committee of Scientific Research (NCSR) at Al-Jouf University (Approval No. 02–09-46).

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Alanazi, A.S. Medical students’ attitudes towards healthcare for people with intellectual disabilities: an experience from Al-Jouf, Saudi Arabia. BMC Health Serv Res 25, 931 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-13030-y