BMC Oral Health volume 25, Article number: 1121 (2025) Cite this article

Orthodontics is a branch of dentistry that focuses on correcting misaligned teeth and bites to improve function and aesthetics. However, improper management can lead to damage of hard and soft dental tissues. This study aimed to assess and compare the awareness of orthodontic benefits and complications among medical and nonmedical students at the University of Science and Technology (UST).

Utilizing an analytical cross-sectional design, data were gathered from 280 medical and 294 nonmedical students (mean age: 19 years; age range: 16–26 years; 52% female) through interviews using a validated questionnaire assessing overall awareness (11 questions), benefits awareness (9 questions), and complications awareness (13 questions). Participants were selected using a two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique. Data were analyzed using the Chi-square test for group comparisons of overall orthodontic awareness, and the Mann–Whitney test for comparing awareness scores of benefits and complications due to non-normal data distribution.

Overall, orthodontic awareness was moderate in both groups and significantly higher among medical students compared to nonmedical students (70.4% vs. 58.2%). There was no significant difference regarding the score of the overall awareness of orthodontic benefits (4.5 ± 2.3 vs. 4.2 ± 2.5; p = 0.131), but the score of overall awareness of complications was significantly higher among medical students (5.6 ± 3.1 vs. 4.6 ± 3.3; p = 0.000).

Overall orthodontic awareness was higher among medical students. While both groups showed similar awareness of treatment benefits, medical students were more aware of potential complications. Enhancing awareness among nonmedical students may support early diagnosis, reduce untreated cases, and improve oral health outcomes. Integrating basic orthodontic education into general health programs could help bridge this gap.

Orthodontics is a specialized branch of dentistry that focuses on diagnosing, preventing, and treating dental and facial irregularities, particularly malocclusions and misaligned teeth [1]. Malocclusion has a multifactorial etiology involving genetic, environmental, and functional factors [2, 3]. Modern diagnostics assess facial aesthetics, occlusion, and masticatory function across all planes [4].

Treatment goals now extend beyond alignment to include improving aesthetics, oral function, and long-term dental health [5]. The multidisciplinary approaches have been increasingly stressed to address both dental and skeletal discrepancies in complex cases [6]. In addition, Orthodontic care also enhances psychosocial well-being, corrects speech issues, reduces trauma risk and tooth wear, and supports periodontal health [5, 6].

On the other hand, Awareness, defined as “the state of being conscious or informed,” is crucial in healthcare contexts, including orthodontics [7]. Orthodontic awareness refers to a combination of self-perceived knowledge, factual understanding, and prior exposure to information related to orthodontics. This includes awareness of treatment options, benefits, and possible complications. Such awareness is particularly important in healthcare settings, as it influences patient engagement, adherence to treatment, and the ability to make informed decisions. In the medical and dental fields, Informed patients are more likely to engage in treatment, adhere to recommendations, and maintain realistic expectations. Awareness of both the benefits and complications of orthodontics is particularly critical among young adults and university populations [7].

Orthodontics has several benefits, and both patients and dentists perceive these benefits from their own perspectives. From the patients’ perspective, the main benefit of orthodontics is the improvement of their dental appearance and the minimization of psychosocial problems related to their dental and facial appearance [8]. However, from the dentist’s perspective, the main perceived benefits are to reduce susceptibility to dental disease, susceptibility to periodontal disease, tempro-mandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction, traumatic dental injury, and carious susceptibility; improve patients’ bite; improve their overall self-image; and correct speech impairment [8, 9].

Despite the numerous benefits of orthodontic treatment, it is not without risks. If not performed correctly or monitored adequately, complications affecting both hard and soft tissues may arise [10, 11]. Therefore, maintaining extremely high standards of oral hygiene practices before and during orthodontic treatment is highly advisable, and it is essential that adequate safety measures are included with this type of treatment [10, 12]. Orthodontic complications can be local or systemic. Local effects include dental issues (decalcifications, decay, enamel cracks, root resorption, pulpitis), periodontal problems (gingivitis, periodontitis, gingival recession), temporomandibular joint dysfunction, soft tissue trauma (ulcerations, hyperplasia), and unsatisfactory treatment outcomes like relapse or dropout [13,14,15]. Recent studies have particularly highlighted enamel demineralization caused by orthodontic brackets and bonding agents. These complications are exacerbated by poor oral hygiene and prolonged treatment durations. Innovations in adhesive technologies are being developed to reduce these effects and support enamel remineralization during treatment [16, 17]. Systemic complications, though less common, may also occur. These include allergic reactions to materials (e.g., nickel or latex), psychological distress, gastrointestinal issues from appliance ingestion, and rare infections such as infective endocarditis in vulnerable patients [12,13,14].

Awareness of these potential complications remains limited in many populations, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Studies from such regions report poor to moderate orthodontic awareness, influenced by factors such as socioeconomic status, educational background, cultural values, and access to specialist care [18, 19]. In the UK and other high-income settings, national orthodontic societies have utilized social media campaigns to enhance public understanding of orthodontic treatment options and outcomes [20]. However, awareness remains inconsistent even among university students. Research indicates that while general awareness of dental malalignment is high, recognition of the term “orthodontics” and understanding of its implications remain limited, with significant variations based on gender, educational background, and urban versus rural residence [18, 20, 21]. Furthermore, a recent cross-sectional study by Yavan and Eğlenen (2022) revealed notable changes in the perception of orthodontic treatment over a 20-year span, highlighting increased aesthetic awareness, evolving treatment motivations, and improved access to care. These findings underscore the importance of continuously evaluating public perception and awareness of orthodontics across generations and sociocultural contexts [22].

Recent studies highlight limited awareness of orthodontics among university students [23,24,25,26]. Studies reveal limited orthodontic awareness among students, with only 50% recognizing “orthodontics” and 31.4% linking it to malocclusion [23, 24]. Conversely, 89.3% awareness of dental malalignment was noted, with urban and female students scoring higher [25]. Another study reported that around 66% of students, regardless of gender, scored high on orthodontic knowledge [26].

Although the use of orthodontic appliances is increasing among young adults in Sudan, particularly university students, there is limited data on their awareness of the associated benefits and complications. At the University (UST), no prior research has assessed this awareness, especially in comparing students from medical and nonmedical faculties. Understanding these differences is essential for orthodontists when managing young adult patients with varying educational backgrounds. This study aimed to assess and compare the levels of awareness regarding the benefits and complications of orthodontic treatment among medical and nonmedical students at the University (UST) in Sudan. We hypothesized that medical students demonstrate significantly higher awareness of the benefits and complications of orthodontic treatment compared to nonmedical students.

The study was conducted at different faculties of the University (UST), Khartoum, Sudan. The university is located in Omdurman and has 4 main campuses: (1) the medical campus, (2) the Information Technology (IT) campus, (3) the engineering campus and (4) the management campus. The numbers of faculties, batches, and students on each of the campuses are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The inclusion criteria encompassed all students aged 18 years and above from both medical and non-medical faculties, excluding dental students. Students who were currently undergoing orthodontic treatment or had a history of previous orthodontic appliance use were excluded to avoid bias due to prior exposure. Dental students were also excluded, as their academic training may influence their level of awareness and introduce confounding factors. Participation was voluntary, and only students who provided informed consent and completed the questionnaire were included in the final analysis.

The sample size for this study was calculated using the formula for comparing two proportions, as available in the Open-Epi software (www.openepi.com). The calculation was based on a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80%, with a design effect of 1.5 to account for potential clustering. The expected proportion of awareness among medical students was assumed to be 30%, based on findings from a previous study [23]. It was hypothesized that nonmedical students would have a 10% lower level of awareness (20%). With a 1:1 ratio between the two groups, the estimated minimum sample size required was 291 participants in each group, yielding a total of 582 participants.

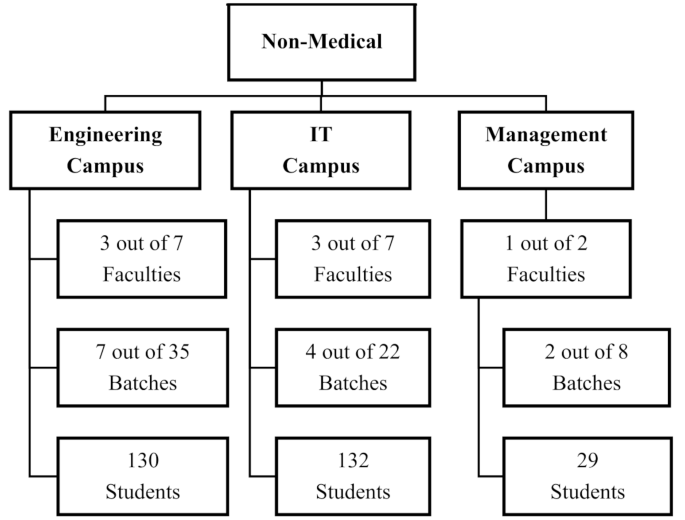

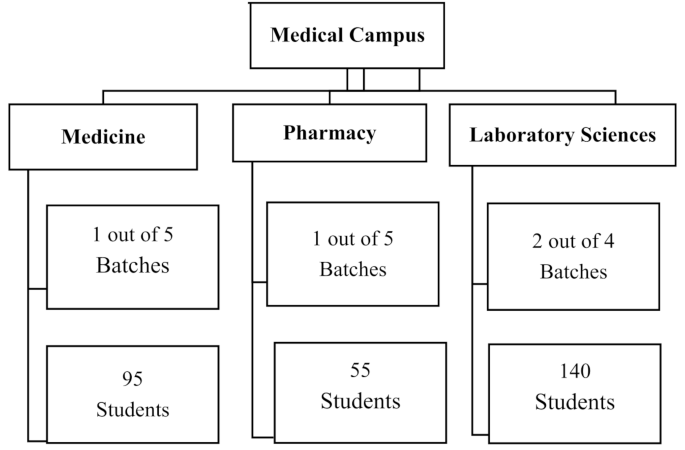

A multistage stratified cluster sampling technique was employed to select participants from the medical and non-medical sections of the University of Science and Technology (UST). The university was first stratified into two primary sections based on faculty type: medical and non-medical. Within each section, further stratification was done—by campuses in the non-medical section (three campuses) and by faculties in the medical section (three faculties)—to ensure comprehensive representation. Table 1 presents the total number of faculties at each campus, the number of batches and the number of students at each faculty.

In the first stage, clusters were defined and randomly selected: faculties within campuses for the non-medical section, and batches within faculties for the medical section. In the second stage, batches within selected non-medical faculties and students within selected medical batches were identified. Students were then selected randomly from these clusters using official student lists and simple random sampling via OpenEpi.

To maintain proportional representation, probability proportional to size (PPS) was applied. For instance, in the non-medical Sect. (8373 students), a sampling fraction of 0.034 was used to allocate the sample across campuses, while a fraction of 0.114 was applied in the medical Sect. (2551 students). This ensured that each subgroup contributed to the final sample in accordance with its population size.

All selections were performed randomly to minimize bias. Figures in the manuscript (Figs. 1 and 2) illustrate the sampling structure and distribution of selected faculties, batches, and students.

The questionnaire was developed by combining questionnaires of two previously published studies. The first section of the current questionnaire was adopted directly from a study conducted in Abha, Saudi Arabia [23]. The second and third sections included statements from a study in Pakistan [27] regarding the expected benefits and complications of orthodontic treatment. In these sections, the statements were reformulated to questions to align with the first section (supplementary file 1).

The questionnaire validation process was conducted by three orthodontic and dental public health experts who assessed content clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness. Their feedback led to refinements that improved the instrument’s validity. To ensure consistent data collection, five trained research team members conducted the interviews. Those were final-year dental students with prior research and survey experience. Inter-rater reliability assessed the agreement among different interviewers administering the questionnaire to similar respondents, while intra-rater reliability tested the consistency of each interviewer’s responses over time. A pilot test was conducted with 10 students from the University (UST), and the same participants were re-interviewed two weeks later. Reliability was measured using the Kappa statistic, with all values exceeding 0.7, indicating acceptable agreement and confirming the questionnaire’s consistency and dependability.

The data were collected from randomly selected medical and nonmedical students. The first section of the questionnaire, adopted from a study conducted in Abha, Saudi Arabia [23], included several questions: four items addressing sociodemographic information (age, gender, college, and year of study) and ten items covering the history of dental visits, purposes of visits, orthodontic awareness, and history of orthodontic treatment. Five orthodontic awareness questions (questions 3, 4, 5, 9 and 10) were summed and then dichotomized into high and low awareness using the median cutoff (low with 0 or only one correct answer and high with 2 or more correct answers) and the variable was named (overall orthodontics awareness). The second section was adopted from another study used to gather information about patients’ expected benefits and side effects following orthodontic treatment [27]. Some modifications were added to be asked as questions to the participants, which included 9 questions about the benefits of orthodontic treatment. The questions cover orthodontic benefits for oral health, oral function, and improvement in psychosocial well-being and confidence. The answers to all the questions were yes, no or I do not know. The yes answers were given a score of 1, and the no, I do not know answers were scored as 0. The total scores/9 were subsequently calculated and are presented as the means and standard deviations (SDs). The third section concerns side effects that could be encountered during the course of orthodontic treatment (4 questions) and complications that may follow the treatment if not handled properly by the orthodontist. Awareness of complications consisted of 6 questions with responses of yes, no and I do not know. The yes answers were given a score of 1, and the no, I do not know answers were given a score of 0. The total scores were subsequently calculated and are presented as the means and standard deviations (SDs).

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The answers in the first section are presented as tables with frequency distributions and percentages. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used for comparisons between groups regarding the responses to questions in each section of the questionnaire, and a p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Chi-square test was also used to compare the difference in percentages regarding the overall orthodontic awareness between the 2 groups.

For the 2nd and 3rd sections, wrong answers were given a score of 0, correct answers were given 1 point, and the scores for the awareness of benefits and complications were presented as the means and standard deviations (SDs). Normality testing was conducted using the Shapiro–Wilk test to assess the distribution of the awareness scores. The results indicated that the data were not normally distributed (p < 0.05), justifying the use of non-parametric methods. Therefore, the Mann–Whitney U test was appropriately used to compare awareness scores between medical and nonmedical students.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Science and Technology following the Helsinki declaration. Permission letters were obtained from the 4 campuses and the selected faculties. Every participant provided informed consent, which included all the necessary information, following the guidelines of the Helsinki declaration. Participant inclusion was completely voluntary, and participants had the freedom to quit the research at any time without being asked about the reason.

The study assessed the response rate and awareness of orthodontics among medical and nonmedical students. The response rate for nonmedical students was 100% (294 students), whereas for medical students, it was 96.2% (280 students). Both groups had nearly equal sex distributions, with similar numbers of males and females. The participants’ mean age was 19 years, ranging from 16 to 26 years. The 4 main campuses and the faculties included in each campus are shown in Table 1. Nonmedical students were randomly selected from 15 batches within seven faculties (we randomly selected 3 faculties and 7 batches from the Engineering campus, 3 faculties and 4 batches from the IT campus, and 1 faculty and 2 batch from the Management campus) (Fig. 1). Medical students were randomly selected from four randomly selected batches within the three medical faculties as shown in Fig. 2.

The first section of the questionnaire evaluated the general awareness of orthodontics. The results, presented in Table 2, revealed that medical students were significantly more familiar with the term orthodontics and orthodontic appliances than nonmedical students were (p < 0.05) and willing to recommend orthodontic treatment for individuals with mal-aligned teeth (p < 0.05). Conversely, nonmedical students primarily perceived malalignment as affecting aesthetics, whereas a higher proportion of medical students reported its impact on overall quality of life.

The second section of the questionnaire assessed participants’ awareness of the benefits of orthodontics. The results, shown in Table 3, indicated that medical students were significantly more aware of the dental health benefits of orthodontic treatment (p < 0.05). On the other hand, nonmedical students were more likely to associate orthodontics with enhancing the smile (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were observed for the other questions.

Table 4 highlights that medical students were significantly more knowledgeable about the potential side effects and complications of orthodontic treatment than nonmedical students were (p < 0.05). They were aware of issues such as eating and drinking restrictions, and teeth cleaning challenges. Medical students were also more aware of potential complications, including tooth surface cracks, inner tooth resorption, inflamed enlarged gum, and unsatisfactory treatment outcomes (p < 0.05).

The five orthodontic awareness questions (questions 3, 4, 5, 9 and 11) were summed and then dichotomized into high and low overall orthodontics awareness using the median cutoff (low with 0 or only one correct answer and high with 2 or more correct answers). Chi-square test revealed that medical students had significantly greater overall awareness of orthodontics (70.4%) than nonmedical students did (53.2%), with a p-value of 0.003. However, no significant differences were found between the two groups in overall mean awareness scores of orthodontic benefits (Table 5). Nonetheless, medical students were significantly more aware (significantly higher mean scores) of orthodontic complications than nonmedical students were (p-value of 0.000, as shown in Table 6).”

Gender-based analysis revealed notable differences in orthodontic awareness between medical and nonmedical students. Among females, medical students showed significantly higher awareness of orthodontic benefits compared to nonmedical peers. However, no significant difference was found among males in this aspect (Table 7).

For awareness of complications, male medical students scored significantly higher than nonmedical males. Although female medical students also had higher scores than nonmedical females, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 7).

This research aimed to gather information about the awareness of orthodontic treatment, which included general orthodontic awareness, awareness of the benefits and side effects and complications. Those were then compared between medical and nonmedical students attending the University (UST). The study revealed that medical students had significantly higher overall awareness of orthodontic treatment and its potential complications. Their enhanced awareness may reflect their academic exposure to health-related topics.

In the present study, participants were asked initially about their dental visits and the reasons of these visits, the reported figures were unsatisfactory among both groups. Approximately one quarter of the medical students reported visiting a dentist in the last six months, and those visits were mostly for routine checkups. While almost one-third of the nonmedical students had visited a dentist in the past six months, and those visits were mostly for treating dental pain. This finding supports previous research in which the number of dental visits was low among the Sudanese population and that most individuals visit dental clinics only when they experience toothache or discomfort [28]. In addition, students with medical backgrounds are more concerned with their dental health. This behavior is consistent with broader patterns in low- and middle-income countries, where awareness of oral healthcare remains limited and treatment is often sought only when symptomatic [28].

The study also included questions regarding the awareness of orthodontics, in comparisons with the previous literature, only few studies have compared orthodontic awareness between those with medical and nonmedical backgrounds. Nevertheless, several studies have evaluated orthodontic awareness among populations with different backgrounds. A previous study performed in Nepal reported moderate knowledge about orthodontic treatment and wearing retainers among patients [29]. Their findings indicated that the awareness of those with nonmedical backgrounds was much greater than that reported in the current study.

In India, two previous studies on orthodontic awareness among 2 different populations have been published. The former was conducted among rural people and revealed that almost 60% of the respondents were not aware of orthodontics, as they were from very rural areas [24]. These findings suggest that socio-educational background and geographic factors influence awareness, aligning with our results. Another study focused on adult age groups and revealed that most of the subjects knew about orthodontic treatment and took treatment at an early age, with a greater percentage of males [30]. Compared with our study, these findings are similar, as both suggest that knowledge of dental care does not significantly differ on the basis of social or educational background. In both populations, the overall understanding of dental appearance and its importance remains relatively consistent across diverse backgrounds.

Two Iranian studies on orthodontic awareness among teachers in different cities reported results similar to those reported for students with nonmedical backgrounds in the current study. A key difference was that these studies did not focus on age differences, instead suggesting that orthodontic treatment is better pursued when the patients are young [31]. Teachers in Iran also viewed orthodontics as having harmful side effects, whereas current study participants recognized both benefits and potential complications [32]. Common findings include high costs and familiarity with orthodontics but a limited understanding of braces [32].

Orthodontics plays a major role in improving facial aesthetics, which in turn boosts psychological well-being and self-esteem [7, 33]. The current study, however, showed only moderate awareness of aesthetic benefits among both groups. This contrasts with findings from studies in urban clinics in Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, where patients had greater appreciation for the psychosocial benefits of treatment [34,35,36]. Unfortunately, the present study found that knowledge of these functional benefits was not as widespread among either group, highlighting an educational gap that may hinder treatment-seeking behavior. With regard to complications, the current study revealed that awareness of potential risks—such as enamel decalcification, root resorption, or gingival recession—was significantly higher among medical students. This reflects their background understanding of treatment risks. However, the awareness levels remain lower than ideal. Recent studies have emphasized the importance of educating patients about iatrogenic risks, especially enamel demineralization and material allergies [16, 17].

In addition, orthodontic terminology comprehension was variable. For example, 41.3% of medical and 30.6% of nonmedical students were familiar with the term “orthodontics,” which is lower than the 50.1% reported in a study at King Khalid University [23]. and consistent with a Nigerian study where 54.1% of medical students answered “yes” to “rearrangement of teeth” as part of orthodontics [26]. This suggests limited familiarity with orthodontic vocabulary even among educated groups. This is critical, as terminology comprehension often affects how well patients understand their treatment options and risks.

Two recent studies revealed somewhat similar findings regarding orthodontic awareness among medical students. One was done among 375 male and female medical students, half of the respondents (50.1%) know the term ‘orthodontics’ which was a bit lower than the current findings [37]. While the other one revealed almost similar findings with 62.2% of the respondents had good knowledge and awareness of orthodontic [38].

Our study also reinforces previous findings from Jazan University, where prior orthodontic experience significantly correlated with better awareness and knowledge [25]. This was consistent in our findings, although we excluded students with prior orthodontic treatment to avoid bias.

The study found that female medical students were significantly more aware of the benefits of orthodontic treatment than nonmedical females, likely due to greater exposure to health education and interest in aesthetics—findings consistent with previous research [39, 40]. Male medical students showed significantly higher awareness of orthodontic complications than their nonmedical peers, possibly reflecting their curriculum’s focus on clinical risks and outcomes [22]. The lack of significant differences in males’ awareness of benefits and females’ awareness of complications may indicate gender-based differences in health priorities or educational content. These findings highlight the need for targeted awareness programs, especially for nonmedical students and males, to support informed decisions and better oral health outcomes.

The study revealed good results in terms of students’ awareness of orthodontic treatment, but the results were lower compared with those of previous studies. The awareness levels were notably and significantly higher among medical students, aligning with our initial assumption and the comparative trend between the two student groups validates our hypothesis. This suggests that academic background, particularly medical education, plays a significant role in shaping awareness of orthodontic care.

Our research is representative and generalizable to University (UST) students, which includes all the campuses. Furthermore, we used a validated questionnaire but checked for any unidentified words and modified the questionnaire. The test retest was subsequently checked via the kappa test. We calculated the sample size using a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80%, a design effect of 1.5 and a prevalence of 30% according to the findings of a previous study (for accurate results), and the sampling was performed via stratified cluster sampling, which further supports the representativeness of our sample.

The limitations of the current study include the use of an interview-based questionnaire due to challenges in translating it into Arabic. A translated version might have been easier for data collection. The study was conducted at a single university and region, limiting its representation of students from other areas. Including multiple universities would provide a broader understanding, nevertheless, UST is considered one of the largest universities with more than 11 thousand students. Additionally, the questionnaire did not address all factors influencing orthodontic awareness, such as socio-economic status, access to healthcare, or/and cultural influences. Despite these limitations, the study offers several strengths. It provides valuable baseline data on orthodontic awareness among university students in Sudan—an area with limited existing research on this topic. The University (UST), where the study was conducted, is one of the largest and most diverse universities in the country, with over 11,000 students from various disciplines, which enhances the internal validity of the findings. Moreover, the study contributes to identifying key knowledge gaps that can inform future educational and public health initiatives aimed.

The results indicate that while overall awareness was moderate, medical students demonstrated significantly higher awareness particularly regarding the complications. This suggests that academic exposure to health-related content positively influences orthodontic knowledge. Therefore, to achieve a more balanced understanding of orthodontic care, targeted educational initiatives should be considered for nonmedical students. Future research should expand the study population to incorporate diverse academic institutions across different regions. This would allow for broader comparisons, help identify regional or institutional differences in orthodontic awareness, and provide more comprehensive data to inform national-level educational interventions.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available. However, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

- LASUCOM:

-

Lagos State University College of Medicine

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- St:

-

Street

- IT:

-

Information Technology

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

The authors acknowledge the faculties at the UST for providing the platform and resources needed to conduct this research. The authors also extend their appreciation to the students who participated and shared their experiences as well as the faculty and administrative staff for their cooperation and guidance throughout the process.

No internal or external funding.

This study was ethically approved by the research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Science and Technology, Sudan following the Helsinki declaration. Written permission was also secured from the different faculties. Written informed consent was taken from each participant before filling out the questionnaire. Participants’ privacy and Confidentiality were assured and the data was analyzed anonymously.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Ali, H.M.H.M., Abukhier, M.B.H., Alsalam, A.M.A. et al. Orthodontic awareness among medical and non-medical university students, Sudan. BMC Oral Health 25, 1121 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-06526-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-06526-w