You may also like...

Leeds United Smashes Nottingham Forest! Farke Hails 'Massive Win' Amid Aina's Disappointing Milestone

)

Leeds United secured a vital 3-1 victory against Nottingham Forest at Elland Road, climbing nine points clear of the Pre...

Studio Shake-Up: DC and Warner Bros. Announce Major Release Date Reshuffles

The DC film "Clayface," featuring a shapeshifting Batman villain, has moved its release date from September 11 to Octobe...

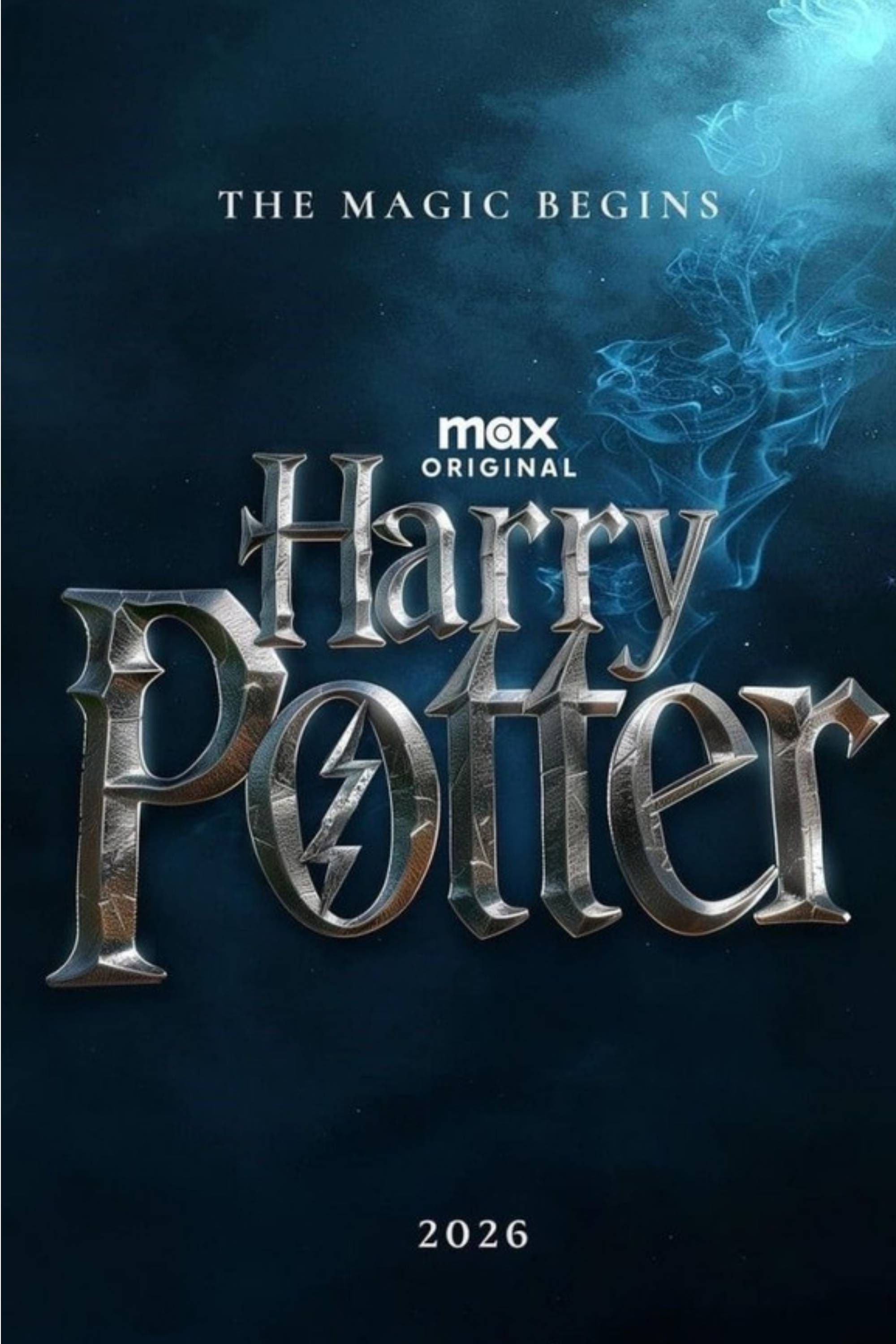

Magical Revival: HBO Max Unleashes Reimagined 'Harry Potter' Universe

HBO Max's upcoming Harry Potter series is rebuilding Hogwarts from the ground up, with new set images revealing detailed...

Joburg's Historic Drill Hall Transformed into Vibrant Arts Sanctuary!

The historic Drill Hall in Joburg's city centre, once a site of the 1956 Treason Trial and later a prosthetic limb facto...

New 'Queen of Africa' Reality Show Offers Grand $50,000 Prize!

"Queen of Africa" has launched as a pan-African reality TV show to champion women's leadership, cultural identity, and a...

OpenAI's GPT-4o Retirement Sparks Outrage: The Unseen Perils of AI Companions

OpenAI's upcoming retirement of its GPT-4o model has sparked intense user backlash, highlighting the profound emotional ...

Unveiling 'SuperCool': A Deep Dive into the Reality of Autonomous Creation

SuperCool redefines creative workflows by acting as an AI 'execution partner' that bridges the gap between raw ideas and...

Microsoft and Women in Tech SA Launch Massive AI Training Initiative Across Africa

The ElevateHer AI programme, a collaboration between Women in Tech South Africa, Absa Group, and Microsoft Elevate, is e...