Labor's Left faction: Albanese, Wong, Plibersek backing Trump's Iran strikes breaks from old guard

Yet, the faction has gone quiet.

The Iran strikes aren’t the first issue on which the Left has shifted. It waved through the AUKUS deal, didn’t revolt over the government’s aborted gambling reforms, and has barely made a noise about Albanese’s intervention to scrap a deal with the Greens to legislate stronger environmental protections. Mandatory minimum sentences for terror offences, which go against Labor’s formal party platform, went through parliament without a fight.

Bill Kelty, a titan of the labour movement who led the Australian Council of Trade Unions in the 1990s, says the entire notion of the Left as an ideological force within Labor no longer makes sense.

“Is there a left-wing view of the Middle East?” Kelty asks. “It’s best to concede the truth, [the Left] doesn’t exist for public policy purposes, it exists for allocating seats and getting representation.

“It’s a delusion to think they exist at all.”

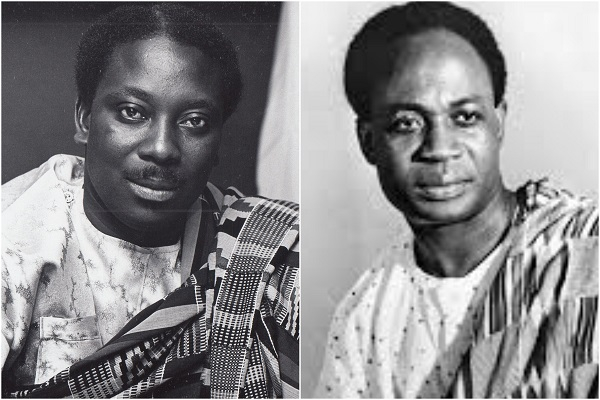

Labour movement stalwart Bill Kelty says of Labor’s Left faction, “it’s a delusion to think they exist at all”.Credit: Justin McManus

But Kelty, who remains connected in labour and business circles, won’t say why the Left has changed. “There might be a whole lot of reasons,” he says.

Loading

Other commentators have offered no shortage of those reasons: the rise of the Greens taking radical voices away from Labor, the ideological dislocation of the Hawke-Keating years, electoral losses under leaders who opposed war or offered expansive policy programs such as Simon Crean and Bill Shorten, the difficulty of a faction defying a prime minister who is one of its members and a surge in professional politicians who prioritise dealmaking over protest.

The Left, in a clear demonstration of the premium it places on unity and a disciplined message, will not defend itself publicly. Sharon Claydon, a Newcastle MP and the faction’s formal convenor, declined to comment.

But there is another view in Labor ranks that the Left has won a practical victory from its rhetorical loss. Albanese’s declaration of support for Trump’s decision to bomb Iran’s nuclear site, Left-aligned sources say, was nothing like John Howard’s commitment to follow the US into Iraq, despite superficial similarities.

No Australian soldiers will invade Iran. No Australian planes or bases aided the American strike. Australia’s support was tersely worded, avoided claiming the attack aligned with international law or was justified by the risk of an imminent Iranian bomb and came only after the attack had happened.

Yet that purely rhetorical support, Albanese’s defenders note, diffused a potential attack on the government for splitting with Australia’s crucial defence partner at a time when China is on the rise.

Opposition Leader Sussan Ley, for example, offered only oblique criticism in response. “Now is a time for Australia to stand with the United States, and Anthony Albanese should be taking every opportunity to do so,” she said.

Albanese is clearly confident his approach is working. “In a time of significant global uncertainty,” the prime minister told the National Press Club in early June, the prescription for successful left-wing government is to “deliver on urgent necessities” at home and play a “stabilising ... role” abroad. “Our destiny”, he told this masthead’s Inside Politics podcast in May, is “to try to be the natural party of government”.

Political historian Paul Strangio, who is an emeritus professor at Monash University, says people who forecast a livelier debate within Labor on policy questions because of its expanded ranks after the election are likely to be disappointed.

“Some might feel more liberated,” Strangio says. “But going on the quiescent reaction to the government endorsing the US strikes, it doesn’t seem so.”

Loading

The loudest voice carrying on the radical nationalist tradition that values a uniquely Australian path in world affairs, which Strangio says was once a defining attribute of the Left, now comes from one of the faction’s old enemies. “If that exists now, the person who most embodies it is Paul Keating, who was the scourge of the Left in the 1990s,” he says. “I’m not saying he’s ideologically changed, but the party has changed and that’s the limb he’s now out on.”

Strangio, who has written books on Labor in Victoria and radical Whitlam government minister Jim Cairns, says there have been some benefits from Labor’s unity.

“You achieve things from the government benches,” he says. Where parts of the Coalition have become more doctrinaire on things like opposing net zero emissions and criticising Welcome to Country ceremonies, Strangio says Labor has been able to occupy the centre of Australian politics. “It’s almost like they’ve swapped clothes in some ways,” he says.

But it has come at a cost, he says, echoing Kelty. He cannot imagine someone like Cairns staying silent on AUKUS or the Middle East. “Good governments have to have contrary voices, and there’s a danger when people hold their tongue too much,” he says. “So there’s a balance to be struck and we’ve veered one way, in my view.”

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.