CIA Documents Detail Quaison-Sackey's Role in Nkrumah's Overthrow

Recent revelations from President John Dramani Mahama have cast a new light on a significant moment in Ghana's history: the overthrow of its first President, Osagyefo Dr Kwame Nkrumah. Speaking at the 68th Independence Day celebration at the Jubilee House on March 6, 2025, President Mahama declared that declassified US intelligence documents confirm the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the United States orchestrated the coup that ousted Nkrumah while he was out of the country. This disclosure, according to the president, solidifies the "verdict of history" on the events of that period, explicitly stating that it was "a coup inspired and engineered by the CIA."

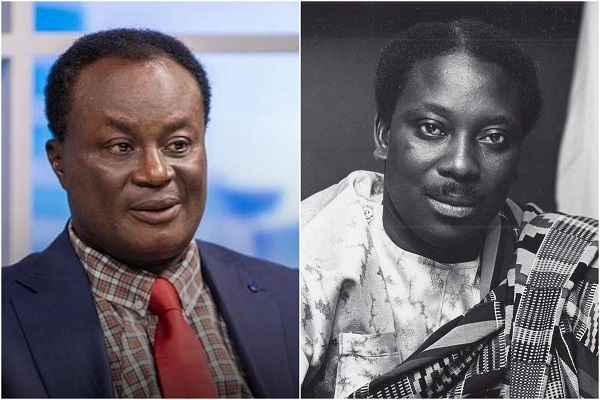

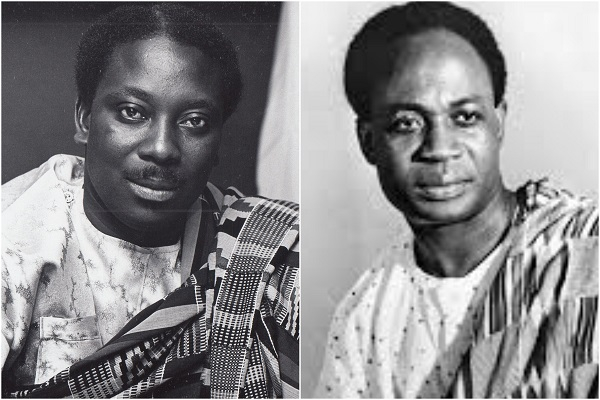

Following President Mahama's assertion, a GhanaWeb investigation into the CIA archives yielded two documents that directly reference Dr Alex Quaison-Sackey, who served as Nkrumah’s Foreign Minister. For decades, Quaison-Sackey has been a figure of controversy, long accused of betraying Ghana’s founding leader to the American intelligence agency. Allegations against him include receiving payment from the CIA and being promised the presidency in exchange for his alleged role in facilitating Nkrumah’s removal from power. While it remains unconfirmed if these are the exact documents President Mahama cited, their content certainly adds layers to the historical narrative.

The first document, dated March 3, 1966, under the heading “THE RECORD Morning Meeting,” mentions Quaison-Sackey's immediate alignment with the new military regime that had seized power. It states, "Reported Nkrumah's arrival in Guinea. There is some possibility that Nkrumah may be so detached from reality as to try to return to Accra. Ex-Foreign Minister Quaison-Sackey has thrown in with the new regime." This particular snippet provides an early indication of Quaison-Sackey's shift in allegiance in the immediate aftermath of the coup, contrasting sharply with his previous position under Nkrumah.

The second document delves deeper, presenting strong insinuations that Dr Quaison-Sackey was indeed a covert CIA operative. It provocatively questions, “Maybe we're being too hasty. Maybe Alex Quaison-Sackey, the right-hand man of the late and unlamented left-wing regime of Kwame Nkrumah, was really a secret CIA agent who worked his way up to be president of the United Nations General Assembly and foreign minister of Ghana and then, at a prearranged signal, hustled Nkrumah off to Peking and engineered the coup which overthrew him.” This passage explicitly links Quaison-Sackey to the orchestration of the coup, suggesting a long-term, calculated infiltration.

Furthermore, this second document details Dr Quaison-Sackey’s controversial actions in the days following the coup. Notably, he disregarded Nkrumah’s direct order to travel to Addis Ababa to defend him at the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now known as the African Union (AU). Instead, Quaison-Sackey reportedly went to London before returning to Ghana. Upon his return, he publicly lauded the new regime as "a breath of freedom" and issued warnings against Nkrumah's potential attempts to regain power with support from Russia and China. This behavior further fueled suspicions about his loyalty and complicity in the coup.

The document also scrutinizes Dr Quaison-Sackey’s tenure as President of the United Nations General Assembly, implying that his public support for Dr Kwame Nkrumah’s pan-Africanist and non-aligned agenda might have been a facade. It asks, "Has it taken Mr Quaison-Sackey this long to see the light? Or has he seen it all along and simply preferred to keep his job and his gold robes and his beaded cane [which the affable gentleman said represented authority] by advancing the cause of a regime which he secretly despised?" The document lists several actions during his UN presidency that, according to the writer, seemed to align more with anti-Western or Soviet-leaning policies, such as protecting the Soviet Union from censure, advocating for communist China, blaming the United States for atrocities in Stanleyville, and urging an invasion of Rhodesia. The text concludes that he "served as spokesman and defender of a regime where freedom was nothing but a word on postage stamps," suggesting a profound disconnect between his public persona and his alleged true allegiances or hidden agendas.

These declassified documents, brought to light by President Mahama’s statements and GhanaWeb’s investigation, intensify the debate surrounding Dr Alex Quaison-Sackey’s legacy and provide additional context to the CIA's historical involvement in Ghana's political landscape. They paint a complex picture of betrayal and covert operations, challenging conventional understandings of this pivotal period in Ghanaian history.