You may also like...

Plastics and Priviledge: How Two Videos Reveal the Country’s Hidden Fault Lines

Two viral videos, one young man carrying plastics to survive, and a billionaire’s son shocked by fuel prices. This is wh...

Africans Who’ve Made Grammy History

Only a handful of Africans have ever crossed the Grammy line. Here are some Africans who made history at the world’s mos...

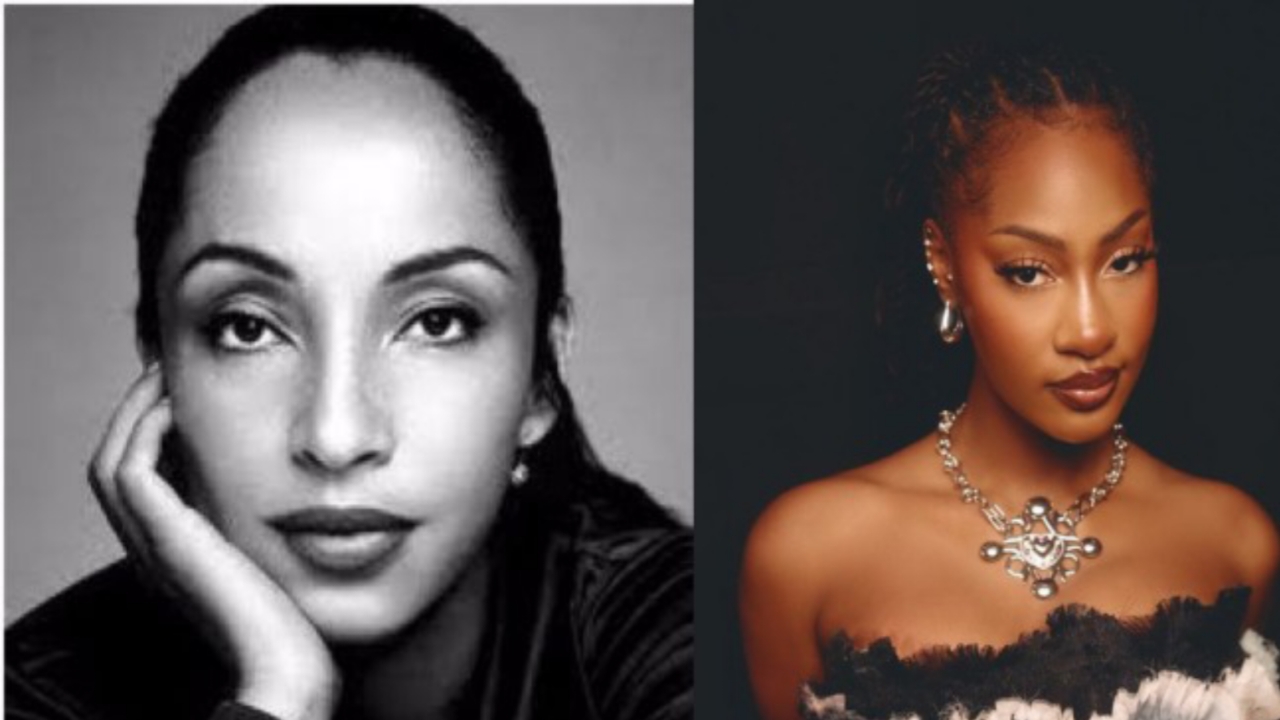

Tems Is Not the First Nigerian Female Artist to Win a Grammy

Tems’ Grammy win made headlines, but a forgotten Nigerian-born icon won decades earlier. Here’s the name most people lea...

Rewind to the Year Nigeria Was Sold in the 1899 Royal Niger Company Deal

In 1899, Britain bought out the Royal Niger Company for £865,000, taking control of territories that would become Nigeri...

Read About The Nigerian Startup Easing Education Access In Africa

Read on how a Nigerian student-led startup is tackling the real problem in education, disorganized access to learning re...

Remote Work in Africa 2026: How to Access Global Opportunities

Remote work is reshaping Africa’s job market. Learn how Africans can access global remote jobs in 2026, the top skills i...

Best and Worst Foods for Heartburn: What to Eat to Reduce Acid Reflux

That burning in your chest is not random. Read about the foods that trigger heartburn, the ones that calm it, and simple...

Is Traveling Really Essential for Personal Growth or Just an Overhyped Luxury?

Some say traveling is the best way to grow and discover yourself, while others call it an overrated luxury. This article...