BMC Psychiatry volume 25, Article number: 528 (2025) Cite this article

Several individuals with depressive symptoms either do not seek help or delay treatment. This study elucidates the effects of various interventions on help-seeking behaviours, key intermediate indicators of behaviour (intentions, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control), and stigma.

Six databases were searched from their inception to January 2024. Two researchers independently conducted study selection, data extraction, and quality appraisal. Data were analysed using Review Manager 5.4 software and STATA 18.0 software.

Thirteen studies were included, encompassing seven types of interventions: positive emotion infusion, information support intervention, mental contrasting with implementation intentions, self-perspective interventions, telephone care management, health information feedback, and depression follow-up monitoring. Existing interventions did not improve help-seeking behaviour in individuals with depressive symptoms (OR = 1.67, 95% CI: 1.05, 2.94, P = .05) but improved help-seeking intentions immediately after the intervention (SMD = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.20, 1.08, P < .001). Subgroup analyses showed that mental contrasting with implementation intentions (SMD = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.37, 0.88) was more effective than positive emotion infusion (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.34) in enhancing help-seeking intentions. Additionally, mental contrasting with implementation intentions improved help-seeking intentions 2 weeks after the intervention (MD = 4.44, 95% CI: 2.60, 6.28, P < .001). Providing information support positively affected attitudes toward help-seeking (MD = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.57, P < .001). No study measured subjective norms and perceived behavioural control. Moreover, available research was insufficient to provide reliable results concerning help-seeking stigma.

Existing interventions improved help-seeking intentions in individuals with depressive symptoms but did not affect help-seeking behaviour, warranting further research. Additionally, researchers should explore the role of interventions on subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and stigma. Future studies should consider long-term follow-up of improved help-seeking behaviour and compare the effects of different interventions.

PROSPERO CRD42024496771.

Depression is a common mental disorder affecting millions of people worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 5% among adults [1, 2]. However, several people with symptoms of depression under-report their condition because of stigma. Depression can have negative consequences, such as dysfunction, reduced quality of life [3, 4], poor interpersonal relationships [5], and even suicide [6]. Nevertheless, effective treatments for depression, including medication and psychotherapy, are available [7, 8]. However, the proportion of individuals with depressive symptoms receiving treatment remains low (16.8–48.3%) [9]. They often choose not to seek help [10, 11] or delay treatment [12]. However, self-guided interventions are less acceptable and less effective [13]. Negative coping strategies can lead to lower symptom remission rates, a higher risk of chronicity [14], and an increased financial burden [15]. One reason for the low treatment proportion may be the lack of proactive help-seeking behaviour. For individuals with mental health problems, help-seeking behaviour is an adaptive coping process encompassing actively seeking help from various resources [16].

Several theories, such as the Health Belief Model, Andersen’s Behavioural Model, the Theory of Reasoned Action, and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), are frequently used to explain behavioural changes [17]. Of these, the TPB is more commonly applied to the field of mental health help-seeking [18]. The TPB states that behaviour can be directly influenced by intentions and perceived behavioural control. Additionally, perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, and attitudes can influence intentions. These indicators have been widely utilised as intermediate variables of behaviour, serving as substitutes for behavioural measurements [19]. Furthermore, several studies have explored barriers to help-seeking among individuals with depressive symptoms. Stigma is one of the most important barriers [20, 21]. It involves processes, such as labelling, stereotyping, prejudice, and dissociation [22]. Individuals with depressive symptoms refrain from seeking help for fear of being labelled as ‘abnormal’ [23]. The importance of subjective norms in explaining behaviour is reflected by people’s concerns about the perceptions of others.

Several interventions improve help-seeking [24] and overcome behavioural barriers [25]. However, few reviews guide on improving help-seeking behaviours among adults with depressive symptoms. Several systematic reviews have elucidated related topics. For instance, a meta-analysis suggested that interventions that improve mental health literacy, reduce stigma, and enhance motivation can have a positive impact [26]. Another systematic review summarised interventions common in low- and middle-income countries, indicating a combination of three strategies, namely awareness raising, identification, and help-seeking promotion, appeared to improve help-seeking behaviour [27]. However, these studies focused on a broader range of participants beyond individuals with depressive symptoms. Another systematic review focused on people with depression, anxiety, or general psychological diseases [17], suggesting providing knowledge enhances help-seeking attitudes. Nonetheless, this review was published in 2012 and provides a qualitative synthesis of only six studies. Several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have since been reported, necessitating supplementing previous findings. Additionally, the effectiveness of digital-based interventions was evaluated in systematic reviews [28]. Previous reviews were insufficiently targeted at depression. However, other systematic reviews have emphasised studies tailored to specific populations [26]. The severity of a mental disease influences help-seeking behaviours [29,30,31]. Interventions aimed at improving these behaviours are less effective in at-risk or general populations, where they may appear irrelevant [32]. These individuals primarily seek help to prevent disease, whereas symptomatic people seek help to alleviate and treat their disease. Symptoms and help-seeking patterns vary across mental illnesses [33], indicating the effectiveness of tailored interventions. Two systematic reviews with children emphasised school-based interventions [34, 35]. However, their results did not summarise interventions aimed at improving help-seeking behaviours. Similarly, neither review targeted individuals with depressive symptoms. Children depend on parental leadership to seek help [36], contrary to adult behaviours. Therefore, interventions designed for children may not apply to adults.

Thus, this study seeks to investigate the effects of existing interventions on help-seeking behaviours, important intermediate behavioural indicators (intentions, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control), and stigma in individuals with depressive symptoms. Subgroup analyses were conducted for each intervention type; nonetheless, the number of comparison groups for each type determined the feasibility of subgroup analyses.

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42024496771). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [37] were followed to conduct and report this study.

Six electronic bibliographic databases, namely PubMed, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, and Embase, were searched from their inception to January 2024. A combination of medical subject heading terms and free-text words was used to search titles and abstracts. An example of the search strategy is given below: (‘help-seeking behavior’ OR ‘help seek*’ OR ‘seek* help’ OR ‘Seek* treatment’ OR ‘health care seeking’ OR ‘seek* care’ OR ‘care seek*’ OR ‘service seek*’ OR ‘treatment seek*’ OR ‘service use’ OR ‘service utilization’ OR ‘health care utilization’ OR ‘help-seeking attitude’ OR ‘Intention to seek help’ OR ‘perceived behavioral control’ OR ‘subjective norms’) AND (‘depression’ OR ‘depressive disorder’ OR ‘depressive’) AND (‘randomized controlled trial’ OR ‘RCT’ OR ‘randomized’ OR ‘randomly’ OR ‘trial’ OR ‘controlled clinical trial’ OR ‘clinical trial’). Detailed search strategies for each database are presented in Additional File 1. Additionally, the reference lists of the included studies were searched. This process was completed independently by two researchers, with any discrepancies resolved through discussions with a third researcher.

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review and meta-analysis were as follows: (a) Participants: adults with a distinct diagnosis of depression, self-reported depressive symptoms, or depressive levels identified through screening scales; (b) Interventions: any intervention aimed at improving psychological help-seeking behaviours; (c) Comparator: the comparison group depended on the type of intervention and possibly included waiting control, treatment-as-usual control, virtual intervention, or no intervention; (d) Outcomes: main outcomes comprised help-seeking attitudes, help-seeking intentions, help-seeking behaviours, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. The secondary outcome comprised the stigma of help-seeking behaviours; and (e) Study design: only RCTs. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) participants with other mental illnesses or comorbid major illnesses; (b) interventions comprised compulsory psychological help-seeking components; (c) studies with already published data; (d) studies without full-text access; and (e) studies written in languages other than English.

All studies retrieved from the databases were imported into Endnote X9 software, and duplicate entries were removed. The titles and abstracts were reviewed to remove studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, study inclusion was conducted after reading the full text. Two researchers independently selected the studies, resolving discrepancies through discussions with a third researcher. Moreover, we independently extracted the following details from the included studies: authors, the year of publication, country, study design, sample size, participants, depression severity, intervention details, outcome measurement times, outcomes, and measurement tools. These details were recorded in an information extraction form. In case of insufficient information, the authors of the original studies were conducted via e-mail.

The risk of bias in each study was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [38]. This tool evaluates seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. Each domain was rated as having a high, low, or unclear risk of bias. This process was conducted independently by two researchers, with discrepancies resolved through discussions with a third researcher.

Review Manager 5.4 software and STATA 18.0 software were used for data analysis. For binary outcomes (help-seeking behaviour), odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. OR > 1 indicated a favourable outcome from the intervention group. For continuous outcomes, the mean difference (MD) and its 95% CI were calculated. When studies used different tools to measure the same outcome, standardised mean difference (SMD) and its 95% CI were calculated. A random effects model was utilised because of variations in intervention methods across studies [39]. P-values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. A narrative summary was provided for studies ineligible for meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochrane Q chi-squared test and the I2 statistic based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 [40]. Heterogeneity was classified according to I2 statistics as follows: 0% to 40% means might not be important; 30% to 60% means may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90% means may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: means considerable heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted to identify the effects of different intervention types on outcomes. Pooled estimates for subgroups were determined by observing overlaps in the 95% CI. In case of no overlap, the difference was statistically significant. Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias for comparisons that included at least five trials [41]. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by sequentially excluding included studies. Meta-analysis results were considered stable if the total effect size did not change.

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagram [42]. A total of 9,214 studies were identified through database searches, and four additional studies were identified through manual searches. After removing 2,916 duplicate studies, the titles and abstracts of 6,298 studies were reviewed. A total of 87 studies were identified for full-text reviews. Of these, 13 met the inclusion criteria, and 10 were eligible for meta-analysis.

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the included studies. The 13 studies were published between 2002 and 2024. These were conducted in the USA (10/13), Germany (2/13), and the UK (1/13). Of these studies, three [24, 43, 44] included two sub-studies that met the inclusion criteria, resulting in 16 sub-studies for the systematic review. Of these, eight each were three- and two-arm RCTs. A total of 8,593 participants were included. One of the studies [45] comprised participants aged over 60 years, whereas one [46] comprised participants aged between 18 and 24 years. Eight studies recruited participants with mild depression at baseline (Beck-Depression Inventory-II scores ≥ 14 points [24, 43, 44, 47,48,49,50] or Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores ≥ 10 points [51]). One study recruited participants with baseline Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report scores > 5 [52], whereas another recruited participants diagnosed by a general practitioner or nurse practitioner with a new episode of depressive disorder or symptoms [53]. Both studies indicated depressive symptoms. Two studies targeted participants who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) or Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID) Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder [45, 46]. One study recruited participants with moderate depression at baseline, indicated by Patient Health Questionnaire-9 ≥ 10 points [54]. Seven types of interventions were applied across the 13 studies: three on positive emotion infusion [44, 49, 50], two on self-perspective interventions [43, 47], two on telephone care management [51, 52], three on information support interventions [45, 46, 48], one on mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII) [24], one on health information feedback [54], and one on depression follow-up monitoring [53]. One study included a 1-year intervention with no follow-up [51]. In one study [24], outcomes were measured immediately and 2 weeks after intervention. Another study measured outcomes 26 weeks after baseline [53]. Two studies conducted a 6-month follow-up [52, 54], whereas another study conducted a 1-year follow-up [45]. The remaining studies measured outcomes immediately after brief interventions [43, 44, 46,47,48,49,50]. The help-seeking intention was primarily measured with the General Help Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ), with one study additionally using the Nydegger’s Strength of Implementation Intentions Scale (SIIS) [24]. Help-seeking behaviour was measured using dichotomous questions. Help-seeking attitudes were measured using five seven-point semantic differential adjectives. The Self-stigma of Seeking Help Scale was the only tool used to measure stigma.

Of the 13 studies, nine were assessed as having a low risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Of these, five studies used a randomiser [43, 46, 47, 49, 50], three used an internet-based system [52,53,54] and one used a random number generator [45]. These nine studies described the allocation concealment. For the blinding of participants and personnel, three studies were rated as having a high risk of bias [51, 53, 54], whereas five were rated as unclear because of a lack of reporting [24, 44, 45, 48, 52]. The remaining studies were assessed as having a low risk of bias. Only five studies achieved blinding of outcome assessment [45, 46, 51, 53, 54]. Ten studies were rated as having a low risk of bias concerning incomplete outcome data [24, 43,44,45, 47,48,49, 52,53,54]. All studies were assessed as having a low risk of bias for selective reporting. One study [45] was assessed as having an unclear risk of bias because of insufficient information concerning other biases. Detailed results of the quality appraisal are presented in Additional File 2 (Fig. 2.1, Fig. 2.2).

Meta-analysis

Random effects meta-analysis warrant at least five studies to reasonably achieve good power and generate valuable statistical inferences [55]. Therefore, when fewer than five studies are included in a meta-analysis, the statistical significance of the intervention effect cannot be reliably inferred.

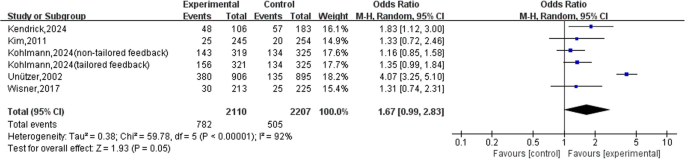

Five studies [45, 51,52,53,54] (including five sub-studies with six comparison groups) assessed help-seeking behaviours after all interventions were completed. A total of 4,317 participants were assessed. All behaviours were measured using a dichotomous question. The interventions did not affect help-seeking behaviours (OR = 1.67, 95% CI: 0.99, 2.83, P = 0.05), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 92%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Results of the Egger’s test showed no publication bias (t = −1.40, P = 0.233). Sensitivity analysis using the sequential exclusion method indicated stable results, with effect sizes ranging from 0.90 to 3.29 (Additional File 2, Fig. 2.3).

Five studies [24, 44, 46, 48, 49] (including seven sub-studies with 10 comparison groups) provided information on help-seeking intentions, which were measured immediately after the intervention. A total of 2,063 participants were involved. Participants differed between different sub-studies of the same study. Two assessment tools, including the GHSQ and SIIS, were used. The interventions influenced help-seeking intentions (SMD = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.20, 1.08, P < 0.001), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 96%, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Egger’s test results showed no publication bias (t = 1.12, P = 0.294). Sensitivity analysis using the sequential exclusion method showed stable results, with effect sizes ranging from 0.47 to 0.74 (Additional File 2, Fig. 2.4).

Subgroup analyses were based on three intervention types. The first type is positive emotion infusion. Two studies [44, 49] (including three sub-studies and five comparison groups) that involved 1,315 participants employed this intervention. A meta-analysis showed that this intervention influenced help-seeking intentions (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.34, P = 0.004), with inconsequential heterogeneity (I2 = 36%, P = 0.18). The second type is an information intervention in the form of a video. A total of 486 participants were involved. In two studies [46, 48] (including two sub-studies with three comparison groups), the intervention did not influence help-seeking intentions (SMD = 1.35, 95% CI: −0.17, 2.86, P = 0.08), with significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98%, P < 0.001). The third type of intervention is MCII. Only one study (including two sub-studies) that involved 262 participants measured the effect of this intervention [24]. The difference between these sub-studies favoured the intervention group (SMD = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.37, 0.88, P < 0.001), without significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.46). Significant subgroup differences were observed (I2 = 79.9%, P = 0.007). The 95% CI of effect sizes of the positive emotion infusion and MCII did not overlap. Therefore, the effect of MCII may be superior to that of positive emotion infusion (Fig. 4).

Only one study [24] (including two sub-studies) measured the short-term effect of intention after the intervention. A total of 262 participants were involved. This study focused on MCII. The same measurement tools were utilised in the two sub-studies, explaining the use of mean differences. Two weeks later, the intervention exerted a significant effect (MD = 4.44, 95% CI: 2.60, 6.28, P < 0.001), favouring the intervention group, without statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.80) (Fig. 5).

Forest plot of mental contrasting with implementation intentions on help-seeking intention 2 weeks after the intervention

One study [48] (including one sub-study with two comparison groups) evaluated attitudes toward help-seeking immediately after the intervention. A total of 370 participants were involved. The two interventions provided public service information support, one offering one-sided and the other two-sided information; both were matched to participants’ attitudinal functions. A significant difference was observed between the intervention and control groups, favouring the intervention group (MD = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.16, 0.57, P < 0.001), without statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.89) (Fig. 6)

Narrative synthesis

Three studies [43, 47, 50] did not provide the data required for meta-analysis; therefore, only a narrative description was provided.

One study [50] provided two interventions and measured outcomes immediately after the intervention. The intervention groups were infused with positive emotions through writing. However, the types of positive emotions differed between the groups. The high-arousal group was infused with exciting emotions, whereas the low-arousal group was infused with calm emotions. Only the high-arousal group with positive emotions differed from the control group (MD = 0.18, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.34, P = 0.021).

Two studies [43, 47] provided self-perspective interventions, which can be divided into two forms: (i) viewing help-seeking behaviour from a self-distancing perspective and (ii) viewing it from a self-immersive perspective. Self-perspective can be stimulated in multiple ways. One study [43] showed no significant difference between the immersive, distancing, and control conditions after the intervention. This study utilised either video with writing or recall with writing to stimulate self-perspective. Another [47] showed that self-distancing yielded higher help-seeking intentions immediately after the intervention than the control condition (P = 0.01). However, the self-immersive condition did not differ from the control condition (P = 0.36). This study utilised integrating thinking with writing to stimulate self-perspective.

One study [47] showed that an intervention utilising a self-distancing perspective on help-seeking behaviour increased positive attitudes toward help-seeking immediately after the intervention compared to the control condition (P = 0.001). However, the self-immersive condition and control condition did not differ (P = 0.06). Regarding stimulating self-perspective, this study utilised combining thinking with writing.

None of the studies assessed subjective norms or perceived behavioural control as outcomes of the intervention.

Two studies [43, 47] (including three sub-studies with six comparison groups) measured self-stigma related to help-seeking after the intervention. In all three sub-studies, the intervention groups used a self-perspective intervention. Neither form of self-perspective intervention improved the self-stigma of seeking professional help, compared with the control condition.

Thirteen studies were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. They elucidate the impact of interventions on help-seeking behaviours, intermediate indicators of behaviour (intentions and attitudes), and stigma in individuals with depressive symptoms. Seven types of interventions were identified. Overall, these interventions enhanced help-seeking intentions and attitudes. Subgroup analyses indicated that MCII appeared more effective than positive emotion infusion in enhancing help-seeking intentions after the intervention. However, meta-analysis results demonstrated the existing interventions did not enhance help-seeking behaviour. A narrative synthesis restricted findings related to stigma. Additionally, existing studies have largely lacked attention to perceived behavioural control and subjective norms.

Help-seeking behaviour is an important outcome. Help-seeking behaviours did not improve after the interventions. The assessed interventions primarily provided information support or motivational enhancement, delivered through text, video, telephone, or offline face-to-face approaches. However, digital interventions can boost help-seeking among individuals with mental health problems [28]. Considering the insufficient number of studies, subgroup analyses based on intervention forms could not be conducted. This warrants more high-quality RCTs to compare different intervention forms. Moreover, behavioural improvement should be measured by follow-up; nonetheless, numerous single brief interventions forgo such measurements. However, behavioural improvement is the most direct indicator of the effectiveness of an intervention. Thus, future intervention studies should measure behaviour to provide stronger evidence.

Intermediate indicators of help-seeking behaviour and stigma are important. According to the TPB [56], pathways can be formed between intermediate indicators and behaviours. Treatment stigma is associated with reduced help-seeking [57]. Additionally, relevant interventions measure improvements in intermediate indicators and stigma.

Results from subgroup analyses suggested that positive emotion infusion improved help-seeking intentions immediately after the intervention. Positive emotions can increase a person’s propensity to act and strengthen social relationships [58, 59]. Individuals experiencing positive emotions are more likely to take steps to develop precise solutions [60]. Thus, infusing positive emotions into individuals with depressive symptoms appears to increase their help-seeking tendencies. The included studies utilised excitement, calmness, elevation, and gratitude as positive emotions. These positive emotions were infused in several ways, such as reading stories, recalling and speaking the emotion, and recalling and writing the emotion. Notably, only five comparison groups from two studies were analysed in the subgroup analyses. Based on the results of each study alone, a significant effect was not produced in all comparison groups. Therefore, the results of subgroup analyses should be cautiously interpreted. More high-quality RCTs are warranted to produce more reliable results.

Providing individuals with information that aligns with their attitudes and psychological motivations positively influences their help-seeking intentions and attitudes. For example, providing information to individuals who value social adjustment about the effect of help-seeking on maintaining relationships has proven effective. This type of intervention is effective because coordinated information attracts attention, promotes reflection, and is more persuasive [61]. Exposure to persuasive information can facilitate help-seeking intentions [62]. One study provided the same information to different participants; the intervention did not improve help-seeking intentions [46]. Considering the limited evidence on this type of intervention, future studies should explore its effectiveness, particularly when the information aligns with the participants.

MCII can improve help-seeking intentions and maintain high intention levels in the short term after the intervention. Such interventions involve asking participants to imagine barriers to achieving a goal and the expected positive outcomes [63]. Subsequently, an ‘if–then’ plan is developed. Subgroup analyses results suggested that MCII may be more effective than positive emotion infusion in improving help-seeking intention. The differences may arise because MCII involves developing an action plan to overcome potential barriers, whereas positive emotion infusion addresses negativity at the emotional level. Considering the limited number of studies analysed, a definitive affirmation of this result cannot be made. Notably, MCII has exerted positive effects on other areas of behavioural change [64,65,66]. Future research should focus on implementing MCII in individuals with depressive symptoms, including the measurement of intermediate behavioural indicators and final behaviours.

Self-perspective interventions measured help-seeking intentions, attitudes, and self-stigma regarding help-seeking. Interventions with a self-immersive perspective, regardless of the stimulation form, had no effect, compared to the control condition. Conversely, interventions that adopted a self-distancing perspective exerted unstable effects. This finding may be attributed to how different sub-studies have defined and stimulated the self-distancing perspective. For instance, thinking from a third-person perspective and imagining a future self are both self-distancing perspectives. Beck’s cognitive theory of depression suggests that individuals with depressive symptoms understand and process information in a more negative way [67]. A self-distancing intervention might temporarily allow participants to escape negative emotionalisation and improve decision-making [68]. Despite a theoretical basis for this intervention, more research is warranted to confirm its efficacy and underlying mechanism.

As intermediate indicators of behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control are central to explaining behaviour and intentions [69]. However, the included studies did not report any results on these outcomes. Subjective norms predict help-seeking intentions, and intentions predict behaviour [33, 70]. The TPB suggests that stable perceived behavioural control and intentions are essential for accurately predicting the occurrence of behaviour [56]. Interventions altering perceived behavioural control may modify behaviour. Therefore, future research should measure perceived behavioural control and subjective norms simultaneously with behaviour. This strategy may provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms by which interventions exert their effects.

This systematic review and meta-analysis has several strengths. First, it only included RCTs, making the results reliable. Second, it focused on individuals with depressive symptoms rather than the general population or individuals at risk for depression. This focus enhances the pertinence of the intervention population. Finally, it summarises not only behavioural improvement but also the intermediate indicators of behaviour and stigma.

However, this systematic review and meta-analysis has some limitations. First, it included a few studies and varied types of interventions. The small number of studies in each meta-analysis indicated that the conclusions drawn from the available data are preliminary and should be interpreted cautiously. Second, more high-quality RCTs should be included in the future because the current number of studies did not support subgroup analyses based on depression severity. Third, only studies written in English were included, and most were conducted in the US, which may have led to an incomplete representation of the literature.

In summary, the available interventions positively influenced help-seeking intentions and attitudes but did not influence help-seeking behaviour among individuals with depressive symptoms. Furthermore, MCII appeared to improve help-seeking intentions more effectively than positive emotion infusion. However, each subgroup included few studies, necessitating further research to confirm these conclusions. Additionally, insufficient evidence suggested that existing interventions improve subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and stigma, warranting more studies. Future studies could consider long-term follow-up of intervention outcomes, particularly regarding behavioural improvements. Furthermore, comparing the effectiveness of different interventions should be considered to guide clinical practice.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information file.

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GHSQ:

-

General Help Seeking Questionnaire

- MCII:

-

Mental contrasting with implementation intentions

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject heading

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- SIIS:

-

Nydegger’s Strength of Implementation Intentions Scale

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behaviour

We thank all the authors from the studies included in this meta-analysis for their prior work and data sharing.

There is no funding for this work.

This research did not involve human and/or animal experimentation.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Ni, S., Cong, S., Feng, J. et al. Interventions to improve mental help-seeking behaviours in individuals with depressive symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 25, 528 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06976-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-025-06976-0