Herdsmen-Linked Abductions in Africa: Untangling the Networks Behind the Violence

The Misleading Labels

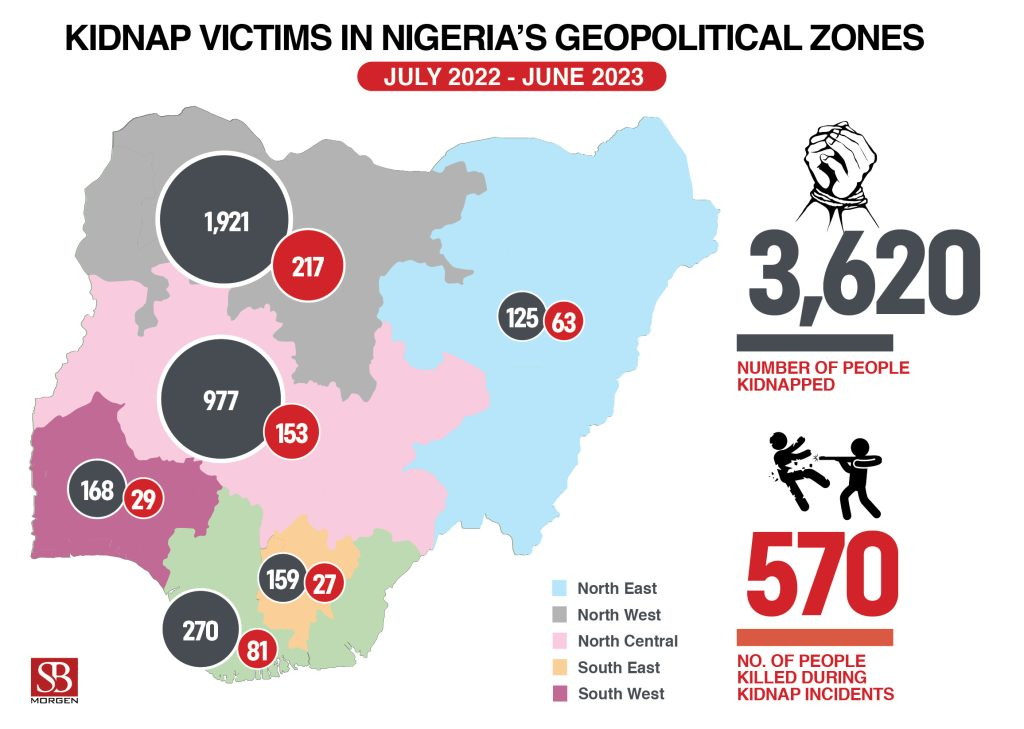

In many parts of Africa, rural communities are living in fear. Kidnappings have become disturbingly common, especially in Nigeria. People are quick to blame “herdsmen attacks,” but honestly, that label misses the mark. Sure, herding routes run through these regions, and you’ll find pastoralist communities there. But most of the kidnappings? They’re the work of armed gangs or extremist groups who use these same areas to hide out. Regular herders get stuck in the middle, often accused or targeted just because they’re nearby. It only adds fuel to the fire, suspicion and tension keep growing in places that are already on edge.

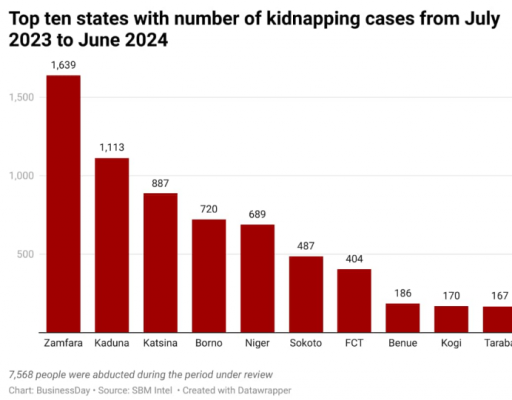

If you look at Nigeria’s northwest, bandit groups rule the headlines. They go after schools, ambush people on the road, snatch villagers for ransom, always chasing money or more control. It’s not about ideology for them. They know the land and stick close to the grazing routes, which helps them dodge security forces. Because of this, people start pointing fingers at Fulani herdsmen. But most of these herders aren’t involved. In fact, they’re often victims.

Then you’ve got actual extremist groups, like Ansaru and ISWAP, running operations in the same zones. Sometimes they claim responsibility for kidnappings, but those cases are usually part of bigger plans, political moves or terror campaigns, not fights between herders. The overlap in territory and tactics just blurs everything. People in these communities can’t always tell who’s behind the latest attack, and the confusion leaves them exposed. Meanwhile, the media and public debates keep mixing up these very different groups.

Calling every attack a “herdsmen” crime has real fallout. Innocent pastoralists get singled out, distrusted by neighbors, and sometimes even threatened by the military. On top of that, it steers policy in the wrong direction, governments end up targeting herders instead of the actual criminals. If we want to fix this, we need to see the difference between where these things happen and why they're happening. Only then can we hope for real solutions.

Patterns and Cross-Border Dynamics

Take the Sahel—places like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Kidnappings there follow a script, no matter who’s in charge. Militants stick to old pastoral routes and those wide, empty stretches of land to pull off their raids. Groups like JNIM and the IS offshoots use the same paths to grab civilians, aid workers, even local leaders. They know the land better than anyone, and they don’t waste time. Really, their tactics look a lot like the bandits over in Nigeria, which just blurs the line between attacks driven by ideology and those about plain old money.

Now, look at the Central African Republic and northern Cameroon. It gets even more tangled. Militias, splinter groups, cattle rustlers, they’re all playing the kidnapping game. Sometimes they want resources, sometimes they’re after political clout, but their methods rarely change: night raids, packs of motorcycles, a quick dash into the bush. All this starts to paint herding communities as the villains, which is just wrong.

These patterns show up everywhere. Armed groups hide in forests, follow livestock trails, and use rural backroads, any spot where they can vanish if things go sideways. They break into small teams and always have someone feeding them local intel. For them, ransom and extortion aren’t just side gigs, they’re the main source of cash. So, in the end, kidnapping isn’t about some big cause. It’s about business.

Sure, a few extremist groups try to dress it up with twisted religious justifications, especially around leadership and non-Muslims. They spin these stories to recruit or make their actions sound righteous. But people see through it. Mainstream Islamic leaders and most communities across Africa call it out for what it is, wrong. Most pastoralists flat-out reject extremism, showing that faith and violence aren’t the same thing.

Implications for Communities and Policy

What’s happening in rural areas goes way beyond the fear that comes with each new kidnapping. These attacks are changing daily life from the inside out. Where people used to gather on shared grazing paths or swap goods in local markets, there’s hesitation now. Neighbors who once worked side by side keep their distance. The trust that held these communities together, gone a little more with every incident blamed (sometimes wrongly) on “herdsmen.” Villages that used to lean on each other for help and resources are pulling apart, and folks just don’t move around or cooperate like they used to. The impact hits women and kids hardest. Parents are scared to let them out of sight, so school and market trips get cut short or stopped altogether. With all this, poverty just gets worse. Economic chances dry up. Divides between groups get deeper.

The suspicion only grows because people keep misidentifying who’s actually behind these crimes. Not every kidnapping pinned on “herdsmen” comes from pastoralist communities. Criminal gangs, bandits, even extremist groups, they’ve figured out how to disappear into the landscape and use old stereotypes to cover their tracks. So when security forces respond with big crackdowns on herder settlements, innocent people get swept up in the mess. That kind of blanket suspicion does more harm than good. It pushes peaceful herders away, the very folks who could help with information and keep things calm. As long as the real culprits hide behind a lazy label, government efforts miss the mark. Nobody gets safer, not farmers, not herders, not students.

Experts say force alone won’t fix this. The real key is smarter, community-based intelligence. People in these areas know who’s coming and going, where folks migrate, and what looks out of place. Instead of leaving security to scattered vigilantes, formal groups with real training could make a huge difference. Quick, informed responses matter. On top of that, investing in new ways for people to earn a living—processing crops, building up livestock businesses—gives young men better options than turning to crime.

There’s also room for more modern tools, early-warning systems, drones to watch risky routes, digital platforms where villagers can sound the alarm when strangers show up. Schools in danger zones need real protection too: alarms, safe rooms, trained guards, and support for kids dealing with trauma.

In the end, calling every kidnapper a “herdsman” just hides what’s really going on. The problem is bigger, organized crime, extremist ideas, environmental stress, a government that’s not doing enough. If we don’t sort out these tangled issues, rural Africa stays stuck in the same old cycles of fear and revenge. Separating peaceful herders from violent actors isn’t just the right thing to do, it’s the only way to make policy that actually works. Until governments and communities start facing the true causes, rural families will keep paying the price, living under a threat that most people still don’t fully get.

You may also like...

Super Eagles Fury! Coach Eric Chelle Slammed Over Shocking $130K Salary Demand!

)

Super Eagles head coach Eric Chelle's demands for a $130,000 monthly salary and extensive benefits have ignited a major ...

Premier League Immortal! James Milner Shatters Appearance Record, Klopp Hails Legend!

Football icon James Milner has surpassed Gareth Barry's Premier League appearance record, making his 654th outing at age...

Starfleet Shockwave: Fans Missed Key Detail in 'Deep Space Nine' Icon's 'Starfleet Academy' Return!

Starfleet Academy's latest episode features the long-awaited return of Jake Sisko, honoring his legendary father, Captai...

Rhaenyra's Destiny: 'House of the Dragon' Hints at Shocking Game of Thrones Finale Twist!

The 'House of the Dragon' Season 3 teaser hints at a dark path for Rhaenyra, suggesting she may descend into madness. He...

Amidah Lateef Unveils Shocking Truth About Nigerian University Hostel Crisis!

Many university students are forced to live off-campus due to limited hostel spaces, facing daily commutes, financial bu...

African Development Soars: Eswatini Hails Ethiopia's Ambitious Mega Projects

The Kingdom of Eswatini has lauded Ethiopia's significant strides in large-scale development projects, particularly high...

West African Tensions Mount: Ghana Drags Togo to Arbitration Over Maritime Borders

Ghana has initiated international arbitration under UNCLOS to settle its long-standing maritime boundary dispute with To...

Indian AI Arena Ignites: Sarvam Unleashes Indus AI Chat App in Fierce Market Battle

Sarvam, an Indian AI startup, has launched its Indus chat app, powered by its 105-billion-parameter large language model...