Ghana's Faith-Based School Conflict: Wesley Girls' Saga Ignites Debate on Inclusivity and Colonial Legacy

A burgeoning national debate has erupted over religious rights in Ghanaian mission schools, centering prominently on Wesley Girls’ High School. The controversy intensified following a lawsuit filed on December 24, 2024, by private legal practitioner Shafic Osman. This action invokes the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under Articles 2(1)(b) and 130(1)(a) of the 1992 Constitution, challenging alleged discriminatory practices against Muslim students at Wesley Girls’, including restrictions on wearing the hijab, fasting during Ramadan, and observing other Islamic rituals. The Supreme Court has since given the Wesley Girls’ Board 14 days to respond to these allegations, with Democracy Hub also admitted as an interested party, raising the stakes for a ruling that could reshape how mission schools manage religious diversity.

Against this backdrop, various political figures and academics have weighed in. Former Sekondi MP, Andrew Egyapa Mercer, expressed concern over President John Mahama’s silence on what has become a national issue. Speaking on JoyNews' Newsfile, Mr. Mercer emphasized the public’s right to know the President’s stance, especially with judicial intervention. He questioned the role of politicians and any past commitments made on such matters, particularly those that might lead to confrontation. Mercer warned that insisting on practices like wearing hijabs where a school’s long-standing policies do not permit it would inevitably lead to clashes. He urged a clear understanding of the school’s actual practices, noting that many Muslims have successfully navigated Wesley Girls’ without issue, suggesting political narratives might distort the facts. He specifically challenged the school to clarify if Muslim students are prevented from fasting during certain periods.

Adding a historical dimension to the discussion, former Tamale Central MP, Inusah Fuseini, argued that the root of educational disparities between religious groups in Ghana lies not in choice, but in the country’s colonial legacy. Mr. Fuseini, speaking after the Attorney General’s formal response to the lawsuit, stated that educational investments by various faith communities were shaped by historical circumstances. He highlighted that formal learning in Africa, particularly Islamic scholarship, predated Western involvement, citing Mali’s early universities. The imbalance, he explained, arose from the colonial system’s privileging of Western knowledge, effectively sidelining existing Islamic educational traditions. He underscored that Muslims had educated their children on the Qur’an and Hadith for centuries, but this form of education was not recognized within the framework of a secular state established through colonization.

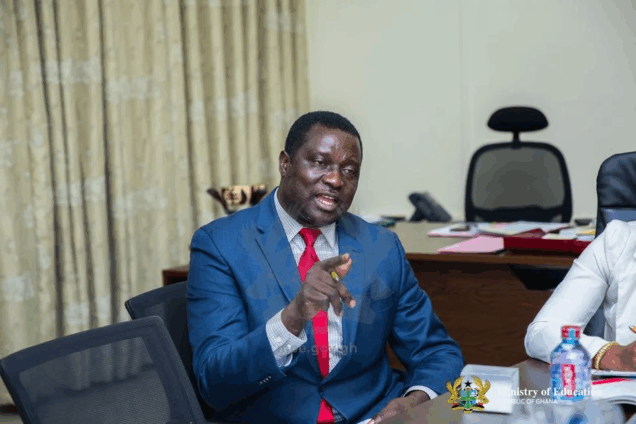

The Interior Minister, Muntaka Mubarak, meanwhile, issued a strong caution against rising intolerance in faith-based schools, whether Christian or Muslim. He urged educational institutions to uphold fairness, balance, and respect for Ghana’s rich religious diversity. While acknowledging that over 80% of Christian mission schools have historically been accommodating, Mr. Mubarak raised concerns about an emerging trend in some Muslim schools. He noted that certain Islamic institutions are beginning to adopt exclusionary practices, mirroring the very behaviors previously criticized in some Christian schools. Examples he cited included insisting on ablution or mosque attendance for all students, regardless of their faith, and refusing to provide lunch during Ramadan for non-fasting students, which he unequivocally labeled as intolerance, regardless of its source.

From an economic and developmental perspective, Professor Godfred Bokpin, an economist and finance professor at the University of Ghana, called for enhanced collaboration between the state and the private sector, including religious bodies, to foster sustainable development. Professor Bokpin acknowledged a historical reluctance among some religious groups regarding formal education and investment but noted a significant evolution in this stance, with many now recognizing education’s value for both faith propagation and societal contribution. He stressed that institutions like schools and hospitals have been vital tools for religious groups to support communities and their beliefs, and the Ghanaian constitution provides a legal framework for this engagement. However, Professor Bokpin also urged caution in the ongoing debates, emphasizing that any reforms must not erode the unique identity or undermine the substantial, long-standing investments made by mission schools. He highlighted the enduring partnership between the state and mission schools in delivering quality education, affirming that no religious body would willingly relinquish its rights over its mission schools. Drawing from personal experience in a Muslim mission school, he illustrated the nuanced differences even within Islamic groups, where Orthodox Muslims might feel uncomfortable in Ahmadiyya schools despite the latter's early and significant educational investments. While commending the progress Muslim communities have made in promoting education, particularly for girls, he firmly stated that this "momentum shift" should not be used to dilute or override the foundational values upon which mission schools were built, given their significant contributions to national development.

The multifaceted debate underscores the complex interplay of religious freedom, historical legacies, educational policy, and national development. As the Supreme Court considers the case, stakeholders are urged to pursue solutions that promote unity in diversity, ensuring a safe and respectful space for all students while upholding the established identities and contributions of mission schools.

You may also like...

When Sacred Calendars Align: What a Rare Religious Overlap Can Teach Us

As Lent, Ramadan, and the Lunar calendar converge in February 2026, this short piece explores religious tolerance, commu...

Arsenal Under Fire: Arteta Defiantly Rejects 'Bottlers' Label Amid Title Race Nerves!

Mikel Arteta vehemently denies accusations of Arsenal being "bottlers" following a stumble against Wolves, which handed ...

Sensational Transfer Buzz: Casemiro Linked with Messi or Ronaldo Reunion Post-Man Utd Exit!

The latest transfer window sees major shifts as Manchester United's Casemiro draws interest from Inter Miami and Al Nass...

WBD Deal Heats Up: Netflix Co-CEO Fights for Takeover Amid DOJ Approval Claims!

Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos is vigorously advocating for the company's $83 billion acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery...

KPop Demon Hunters' Stars and Songwriters Celebrate Lunar New Year Success!

Brooks Brothers and Gold House celebrated Lunar New Year with a celebrity-filled dinner in Beverly Hills, featuring rema...

Life-Saving Breakthrough: New US-Backed HIV Injection to Reach Thousands in Zimbabwe

The United States is backing a new twice-yearly HIV prevention injection, lenacapavir (LEN), for 271,000 people in Zimba...

OpenAI's Moral Crossroads: Nearly Tipped Off Police About School Shooter Threat Months Ago

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI disclosed it had identified Jesse Van Rootselaar's account for violent activities last year, prior ...

MTN Nigeria's Market Soars: Stock Hits Record High Post $6.2B Deal

MTN Nigeria's shares surged to a record high following MTN Group's $6.2 billion acquisition of IHS Towers. This strategi...