Fighting pain with courage: The sickle cell anaemia warriors of Kisumu

In Kisumu, Kenya’s third-largest city, life flows like the waters of Lake Victoria—sometimes calm, sometimes turbulent. Known for its tilapia, fiery politics, and vibrant markets, the city stands tall as a regional hub in Nyanza.

Yet, amid this energy lies a silent health crisis. Sickle cell disease—a condition inherited in silence—has quietly embedded itself in Kisumu’s DNA, affecting thousands and pushing struggling families to the brink.

It’s 7pm in Kisumu. While most residents are settling down for dinner, a different scene unfolds. Children and adults gather quietly at a local venue. They are not here for leisure but for purpose. These are sickle cell warriors, attending a dinner hosted by the Kisumu County Government to discuss the pressing challenges they face. Despite their struggles, they speak with pride and resilience.

“My name is Rehema Akoth. I’m 42 years old, a mother to a 13-year-old boy, and I live in Kisumu. I was diagnosed with sickle cell anaemia at six months old—at least that’s what my mother used to tell me. I never stayed with her for long. When I turned one, my father took me away, and I lived with him and my stepmothers,” she says.

“I had to grow up with three stepmothers who never understood my condition. Whenever I had a crisis, they would accuse me of pretending. My father, a businessman, was hardly around. I endured crises for days without any medical attention.”

Sickle cell is unpredictable, according to Rehema. “You can have a crisis at any moment. Sometimes it begins with a strange sensation, a signal in your mind or body. At times, someone might accidentally bump into you, and suddenly your whole body is in pain. The crisis can strike in your sleep, and you wake up feeling like it is a dream—only to realize it’s real.”

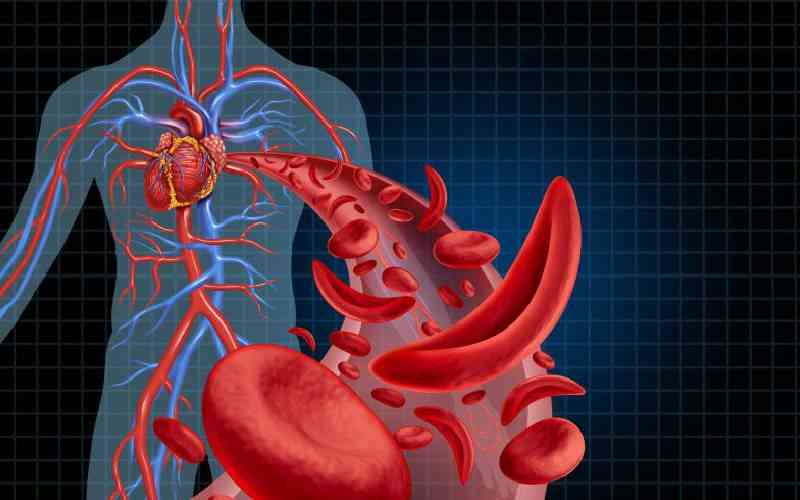

According to Dickens Lubanga, a paediatrician at Bungoma County Referral Hospital, sickle cell anemia is a congenital disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. “This means a child must inherit two copies of the mutated hemoglobin gene—one from each parent—for the disease to manifest. If only one mutated gene is inherited along with a normal one, the individual will have what is referred to as the sickle cell trait.”

“People with the trait usually do not experience symptoms, but they can still pass the mutated gene to their children. The disease is caused by a mutation in the gene that produces hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells responsible for carrying oxygen. This mutation results in red blood cells becoming stiff, sticky, and shaped like a sickle or crescent rather than being round and flexible. These misshapen cells tend to block blood flow in the vessels, leading to frequent pain episodes, infections, and damage to organs,” he adds.

“Managing the condition requires constant care. I drink lots of water and porridge, eat green vegetables, and avoid red meat and sugary drinks. I prefer white meat and fresh juices. I once got married, but it didn’t last. I believe it was partly due to the burden of living with sickle cell—it’s expensive, emotionally draining, and requires deep understanding. My husband left, but I’m thankful for my son. I’m afraid to try marriage again, fearing rejection for the same reasons,” Rehema explains.

“I didn’t go to school much, and I don’t have a stable job. Sometimes I can’t work at all due to my health. I remember a major crisis in 2005 that almost cost me my left hip, and another in 2016 that left my lower lip numb. Most people don’t notice it, but I can feel the heaviness when I talk or eat. I know my body so well that I can sense an impending crisis—dry throat, fatigue, or infection—and take early precautions.”

There are many myths about sickle cell. According to Rehema, people say they can’t give birth or have periods, and that they are cursed. “When I was younger, a boyfriend once told me that giving birth would kill me. But I did give birth. Some people even say sicklers are supposed to be skinny, weak, or look strange with big heads, protruding bellies, and thin limbs. None of that is true.”

“Growing up, I faced stigma at school. Some kids didn’t want to be near me. They’d whisper about me being a beggar or ask intrusive questions. I kept to myself. Now, for pain management, I use Tramadol injections—just like diabetic patients manage their condition with insulin. The pain is too severe to endure without medication.”

Rehema says living with sickle cell is like raising three children: “My son, my health, and the bills that come with it. Right now, I owe Sh7,800 to SHA, and without it, I can’t access services.”

Recently, the Kisumu County Government partnered with Yunigen Pharmaceuticals to introduce a new drug, Scadamine. Unlike hydroxyurea capsules, which are hard for young children to take, Scadamine dissolves in water. “We hope it will be affordable. Kisumu government is improving—now when we go to the hospital, nurses understand our condition better, and we have our own beds. That’s a huge step forward.”

Michelle Omulo, 32, is another warrior. “I was diagnosed at Kenyatta National Hospital when I was three. My mum wasn’t shocked—she had seen her sister-in-law, my late aunt, live with sickle cell too. But she didn’t fully understand the genetics behind it.”

Back then, treatment options were limited. “We relied on folic acid and, occasionally, Paludrine, which was scarce. Life has been far from easy. In high school, my mum enrolled me in a day school to monitor my health. I had frequent crises. Then in Form Two, I suffered a mild stroke in August 2010, affecting the right side of my body. I limp now because of that.”

“Stigma followed me everywhere—from school to the workplace. I’m a filmmaker, and I’ve faced rejection on film sets because of how I walk. I even made a short film called Genotype, available on my YouTube channel, Victoria Youth and Film Empowerment.”

Michelle has faced relationship struggles similar to Rehema. “I used to wait before telling a man about my condition. Once they knew, they assumed I would die young, couldn’t be intimate, or wouldn’t be a ‘normal’ wife—and they’d leave. That hurt deeply. So I decided to stay single and focus on my dreams.”

“The Yunigen partnership with Kisumu County is promising, since it will bring the drugs to our potential reach. I attended Yunigen Pharmaceuticals partnering with county government of Kisumu—the way they explained to us sicklers it’s a promising move and I’m hopeful many sicklers will benefit,” Michelle says.

Speaking at the agreement signing, Kisumu Governor Anyang’ Nyong’o said: “This is not just about documents. It’s about delivering real hope to our children and families who have endured this silent suffering for far too long.”

“Many warriors come from humble backgrounds. We need daily medication and support, but most of us are jobless.” Michelle urges the government to allocate funds for medication and employment opportunities and to include sickle cell warriors in development plans.

“The myths—like sickle cell being a curse or witchcraft—must be debunked. It’s genetic. Many parents don’t even know their children have sickle cell. I haven’t had a major crisis in nearly three years now. It’s all about consistent medication and avoiding stress. To fellow warriors, don’t lose hope. I once had none, but I stood up and became an advocate.”

Walter Ombere, a recent Form Four graduate, is also living with sickle cell. “I was diagnosed at just three months old. My mom was supportive from the start. She later discovered the gene came from my father’s side.”

“Growing up, I was frequently hospitalised—sometimes missing up to a month of school. But I still managed to pass my exams and go to high school, where I had fewer crises. I began understanding my condition in Class Six, after a doctor sat me down and explained sickle cell and how to manage it. I now use my passion for performing arts to create awareness. I perform in places like Obunga, Nyalenda and Manyata to educate communities.”

“Pain crises vary. When they hit, I might be in hospital for three or more days. I manage my condition with hydroxyurea, folic acid, and plenty of water to ease blood flow and oxygen absorption. I have faced stigma from strangers. Some mock my small body or question if I’m a child or a man. But I turn their ignorance into motivation.”

“The Kisumu County Government’s partnership with Yunigen is promising. If they begin distributing affordable medication, it could be a game changer. Currently, Victoria Annex provides free hydroxyurea to those with an active SHA card—each tablet costs Sh35 outside. That support makes a huge difference. To fellow warriors, join support groups. I’m part of Tumaini, which includes professionals who guide us.

“When my hemoglobin dropped to 5.0, I was transfused and it rose to 6.7. Transfusions and a balanced diet—especially omena— help. We are fighters. And with the right support, we can thrive.”

You may also like...

Diddy's Legal Troubles & Racketeering Trial

Music mogul Sean 'Diddy' Combs was acquitted of sex trafficking and racketeering charges but convicted on transportation...

Thomas Partey Faces Rape & Sexual Assault Charges

Former Arsenal midfielder Thomas Partey has been formally charged with multiple counts of rape and sexual assault by UK ...

Nigeria Universities Changes Admission Policies

JAMB has clarified its admission policies, rectifying a student's status, reiterating the necessity of its Central Admis...

Ghana's Economic Reforms & Gold Sector Initiatives

Ghana is undertaking a comprehensive economic overhaul with President John Dramani Mahama's 24-Hour Economy and Accelera...

WAFCON 2024 African Women's Football Tournament

The 2024 Women's Africa Cup of Nations opened with thrilling matches, seeing Nigeria's Super Falcons secure a dominant 3...

Emergence & Dynamics of Nigeria's ADC Coalition

A new opposition coalition, led by the African Democratic Congress (ADC), is emerging to challenge President Bola Ahmed ...

Demise of Olubadan of Ibadanland

Oba Owolabi Olakulehin, the 43rd Olubadan of Ibadanland, has died at 90, concluding a life of distinguished service in t...

Death of Nigerian Goalkeeping Legend Peter Rufai

Nigerian football mourns the death of legendary Super Eagles goalkeeper Peter Rufai, who passed away at 61. Known as 'Do...