You may also like...

The Story Behind Elon Musk’s Record-Breaking xAI–SpaceX Merger

Elon Musk’s $1.25 trillion xAI–SpaceX merger reshapes AI, space, and global tech. Here’s what it means for investors, us...

They Didn't Choose Their Parents: Do Nepo Babies Still Deserve the Blame?

The Nepo vs Lapo debate has taken over Nigerian social media, but is it fair to blame nepo babies for their privilege? T...

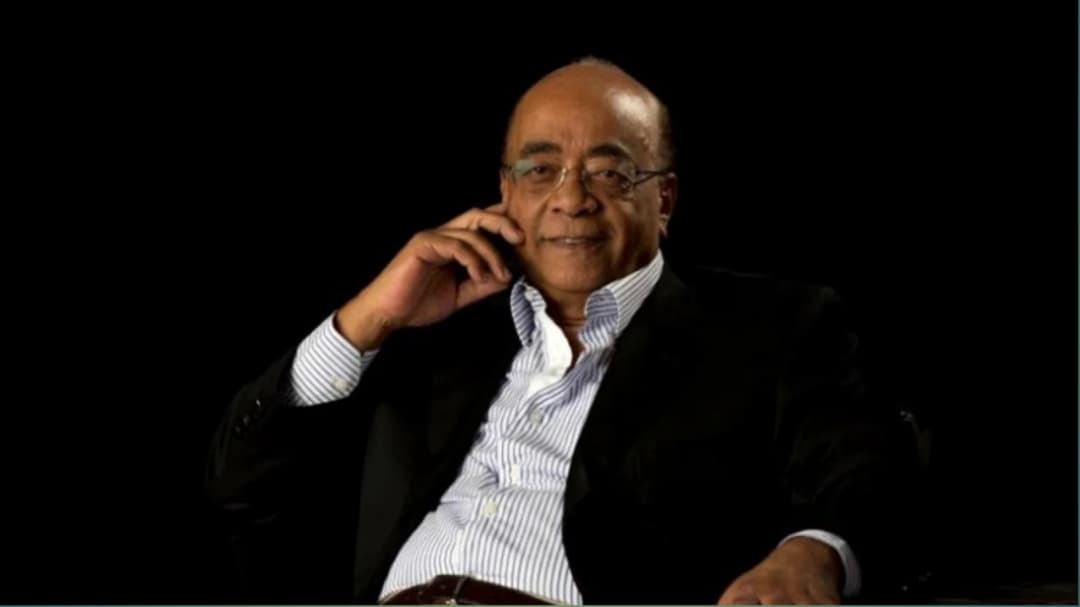

Mo Ibrahim: Africa’s Telecom Tycoon and Champion of Good Leadership

Read the inspiring story of Mo Ibrahim, the African telecom billionaire who built his empire with integrity and now uses...

Where is ₦5, ₦10, and ₦20 notes – Could the ₦50 Note Be Next?

Nigerian currency notes—₦5, ₦10, and ₦20—are disappearing due to inflation, rising production costs, changing spending h...

Top Crypto Investment Strategies for 2026

Looking to invest in cryptocurrency in 2026? To stay ahead in the crypto market with these proven investment strategies,...

The 16-Year-Old Who Called Out America on Live TV (and Changed Nigerian Broadcasting Forever)

In 1957, a fearless 16-year-old Nigerian challenged American racism on live TV and went on to redefine broadcasting in N...

The Kenyan Government Is Warning Against Cash Bouquets And Here’s What It’s Really About

Kenya’s Central Bank warns against Valentine’s cash bouquets. Read what this is really about and how damaged currency af...

Plastics and Priviledge: How Two Videos Reveal the Country’s Hidden Fault Lines

Two viral videos, one young man carrying plastics to survive, and a billionaire’s son shocked by fuel prices. This is wh...