'Eddington' Review: Ari Aster's Brazenly Provocative Western thriller

It’s all too common today to see ambitious filmmakers turn their movies into “statements” that fit all too neatly into preset ideological boxes. But in “Eddington,” his teasingly audacious, bracingly outside-the-box cosmic sociological Western thriller, writer-director Ari Aster (“Beau Is Afraid,” “Midsommar”) gleefully tosses any hint of liberal art-house orthodoxy to the winds.

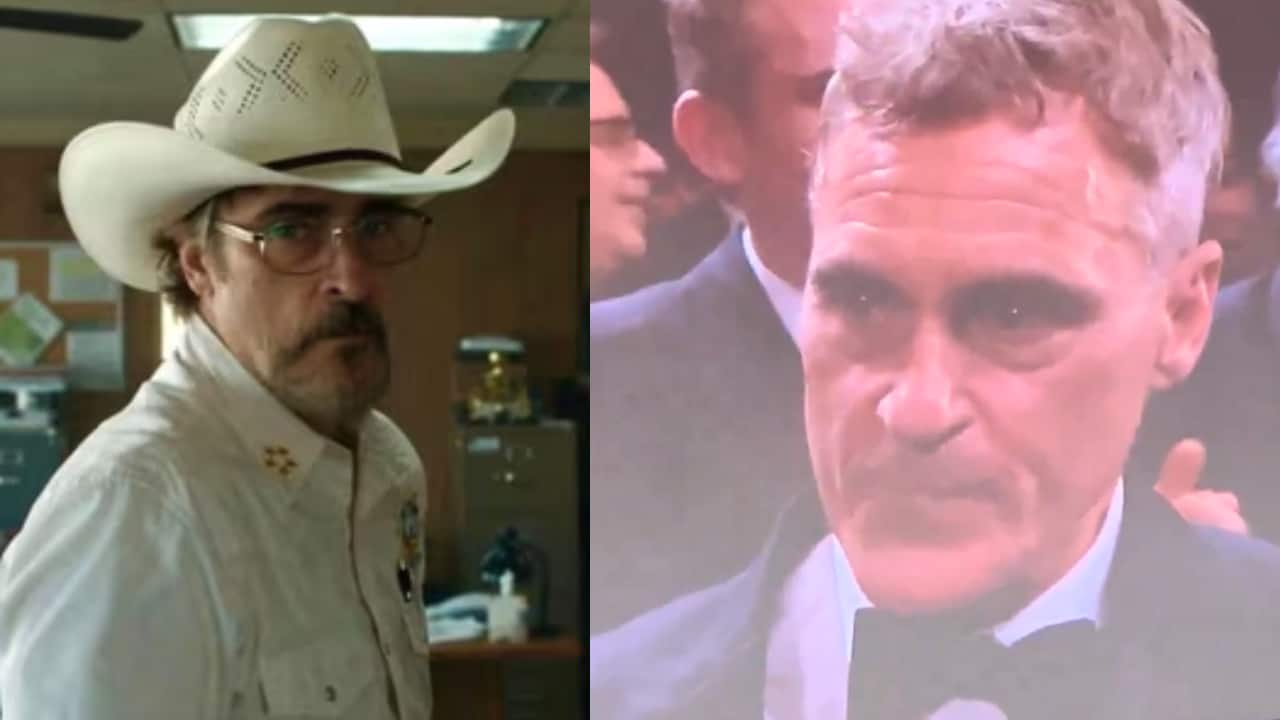

The film is set in the desert city of Eddington, New Mexico, during the COVID summer of 2020, and the first indication that it’s going to offer a major tweak of conventional wisdom is that the protagonist, Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), who’s the city sheriff, is just about the only person in town who refuses to wear a face mask. He’s an asthmatic, but he’s also got a brazen contempt for the COVID stats about transmission, and for the general notion of lockdown. Is his stance speaking for the movie’s? That’s tougher to pin down, since Joe, on the one hand, is the character we’re asked to identify with, but Phoenix plays him as a shambolic screw-up, earnest and benign but basically a walking mess.

Not long into the film, the George Floyd murder occurs, and the protests that take place in Minneapolis and other American cities trigger a small local movement in Eddington of anti-racist youth. The film is unambiguous about portraying them as a pack of deluded narcissists whose conception of themselves exemplifies the very privilege they’re out to overthrow. Aster isn’t merely mocking them; his real point is that moralistic self-righteousness has become a kind of addiction in America. Nevertheless, that he kicks off his film by skewering COVID protocols, only to lampoon the radical-chic fervor of middle-class white kids, may make you wonder, for a moment, if Ari Aster has turned into some right-wing hipster auteur tossing cherry bombs attached to Fox News talking points.

Actually, it’s not nearly so simple. In “Eddington,” Aster is dead serious about dramatizing what he views as the looking glass that America passed through during the pandemic era. He’s targeting that moment as The Great Crack-Up, the moment when the country lost its collective mind. But in the film there are many components to that, drawn from a wide cultural-ideological spectrum. The movie does show sympathy for the increasingly mainstream view that the sense of control that dominated the COVID years went too far. That Eddington, while larger than a small town — it’s a place of sprawling streets and buildings — appears to be all but abandoned is something that casts its own eerie spell; it stands in for a nation that’s been hollowed out, depleted, robbed of its hope for the future. When a teenage boy is chewed out by his father for having joined in a “gathering” (i.e., he met up with half a dozen of his friends in the park), we feel the creeping unreality of it.

But COVID is just the trigger. “Eddington,” while not a comedy, showcases an angry, sinister, and maybe crazy new America that it views with a deadpan tone of trepidatious glee. And the movie presents us with a fully scaled vision of that transformed society. As Aster presents it, what happened to America is about COVID and everything the relentless rules of the pandemic did to us. It’s about the rise of the new scolding moral absolutism. It’s about how conspiracy theory, which used to be the province of the liberal-left, became the new crackpot paradigm of Middle America, to the point that attacking the government for lies and coverups (like, you know, the plandemic) went from being a rebel stance to a kind of authoritarian reflex.

It’s also about the creeping paranoia of gun culture, and about the paranoia that has gathered around the all-too-real issue of pedophilia (a trend that actually started with the day-care abuse trials and missing-children milk cartons of the 1980s, then picked up contemporary steam with QAnon and Pizzagate). It’s about how social media became the dark hall of mirrors that magnified all these toxic forces, to the point that the distorting of reality almost seemed to be the buried reason for it all. And it’s about the ominous rise of big tech (embodied here by a massive proposed data center from a corporation called solidgoldmagikarp), which is both the orchestrator and beneficiary of that hall of mirrors.

That sounds like a lot for a movie to chew on, but “Eddington,” for all its heady themes, is a far more nimble and relatable entertainment than Aster’s last film, the masochistic surrealist art nightmare “Beau Is Afraid.” The new movie is two-and-a-half-hours long, and it ultimately does take a turn into something ominously out there. But for most of it Aster lures us in by telling a grounded and weirdly arresting story, which the age-of-the-pandemic themes sort of flow through.

It all begins with Phoenix’s desperate, lackadaisical, borderline incompetent sheriff coming under fire for his anti-mask stance, then making the decision to challenge the city’s mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal), with his posh backers and facile grin. Joe decides to run for mayor himself, but these two men have an enmity that reaches back to a buried personal scandal: Twenty years before, Garcia slept with Louise (Emma Stone) when she was 16 and got her pregnant. She had an abortion and went on to marry Joe. Joe and her are still together, living in an isolated ranch house atop a small mesa (along with Louise’s blustery mom, played by Deirdre O’Connell; she moved in during COVID). But Louise has a history of mental illness, and Emma Stone plays her as the image of frail, washed-out vulnerability.

The marriage is hanging by a thread, and the thread gets cut when Austin Butler, acting with the smoothness of the young Johnny Depp, shows up as Vernon, who’s part of what appears to be a cult devoted to victims of child sexual abuse. Vernon sits in the Crosses’ kitchen and tells his story, a piece of retrieved memory that replaced his other memories, and it’s so garishly far out that we think: Is he about saving people or implanting them with new identities? More to the point: Is this what “salvation” is becoming in America? Louise, in thrall to Vernon’s therapeutic snake oil, has soon abandoned Joe, and this leaves him devastated.

Aster is out to capture how the dislocation of reality that’s becoming the coin of the realm isn’t just a political/media phenomenon; its tentacles reach right into the heart of intimate relationships. And we see the same sort of social-turned-emotional freakout when the Black Lives Matter movement hits Eddington. The film never doubts the validity of the protests that rose up against the murder of George Floyd. But it does satirize the performative aspects of a certain brand of middle-class radicalism, and the way that this ensares various members of the community, like Sarah (Amèlie Hoeferle), who becomes such a self-lacerating true believer that she starts to sound like a member of the Weather Underground; Brian (Cameron Mann), a local kid who starts out just wanting to flirt with Sarah, then finds his identity undergoing an extended mutation (with a real payoff at the end); and Michael (Micheal Ward), the Black cop who works for Joe and couldn’t be more of a straight-arrow, but winds up the victim of a group of terrorist extremists who are out to “save” him.

There’s no question that in “Eddington” Art Aster makes himself a scalding provocateur, the same way Todd Field did in “Tár” when he staged the confrontation at Juilliard between Cate Blanchett’s Lydia and the BIPOC student who questioned her devotion to dead-white-male composers. Yet as much as nailing down the precise point-of-view of “Eddington” is destined to be the subject of numerous incendiary debates, I’d argue that this is very much not a case of Aster becoming some young A24-approved version of David Mamet. What he captures in “Eddington” is an entire society — left, right, and middle — spinning out of control, as it spins away from any sense of collective values.

The movie is about the center not holding, and you feel that refracted through every pleading stammer of Phoenix’s alienated, sad-sack performance. It’s not quite up there with his great ones, but it’s not one of his mumbly showboat ones either. There’s a bitter poignance to Joe, who’s in way over his mussy-haired head. When he finally takes matters into his own hands, you keep rooting for him even as he does something indefensible. For a while, the film becomes a darkly ambling thriller, one that plays Joe’s investigative team off the efforts of a local Pueblo officer, Butterly Jimenez (William Belleau), who we suspect might turn out to be our hero’s version of Inspector Javert.

But just when you think you’ve got “Eddington” pinned down as a coherent and even conventional suspense tale, the movie wriggles out from under you and enters a terrain of stranger things. It doesn’t get lost in the grim funhouse of its own conceits, the way “Beau Is Afraid” did. But it does grow a little…abstract. There’s an indulgent side to Ari Aster, and though it’s more under control here, you can feel him giving him into it. Yet it’s also inseparable from what makes him, in “Eddington,” such a stimulating filmmaker. He wants to show us the really big picture, and while “Eddington” isn’t a horror movie, it puts its finger on a kind of madness you’ll recognize with a tremor.