You may also like...

Track Star Noah Lyles Stunned by Major Awards Snub, Vows Huge 2026!

)

Despite a dominant 2025 season marked by a fourth consecutive 200m world title, sprinter Noah Lyles was notably snubbed ...

Mohamed Salah's Fiery Outburst Ignites Fury Among Ex-Liverpool Stars!

)

Mohamed Salah's explosive public criticism of Liverpool and manager Arne Slot has ignited a major controversy at Anfield...

Supercop Secrets Revealed: Stanley Tong on Jackie Chan's Trust and Action Film Magic

Director Stanley Tong recounts his incredible journey from a severely injured stuntman to a visionary filmmaker, culmina...

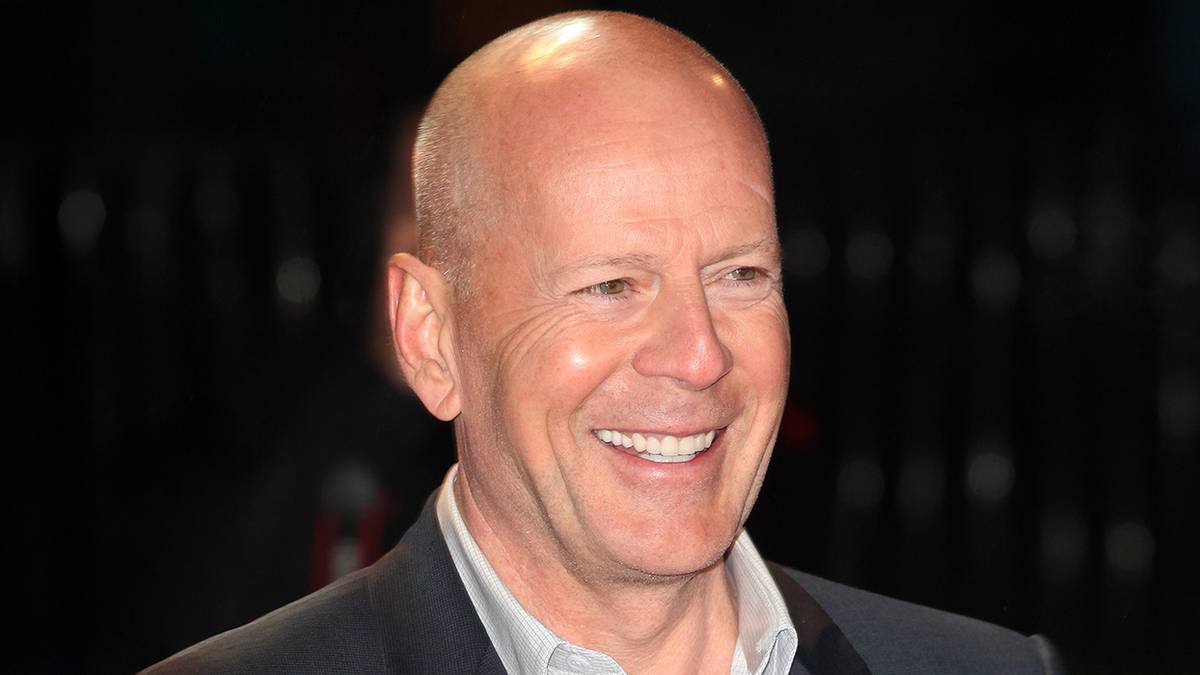

Bruce Willis' Final Role A Streaming Hit, Dominating Charts

Bruce Willis's 2022 action thriller, Gasoline Alley, is finding new life on Paramount+, becoming one of the top-streamed...

Diddy's Mother Unleashes Fury on Netflix Docuseries' 'False' Abuse Claims

Sean Combs' mother, Janice Combs, has vehemently refuted claims in the Netflix docuseries "Sean Combs: The Reckoning," l...

Love Blooms: Glad Finds Forever With Samuel After One Magical Date!

Discover the heartwarming love story of Glad and Samuel, a journey that began with online connection, navigated initial ...

Peter Brandt's Dire Bitcoin Warning: Bulls Prepare for Impact!

Veteran trader Peter Brandt has issued a stark warning for Bitcoin bulls, predicting significant price corrections based...

Dogecoin's Epic 12-Year Saga: Founder Spills Origins!

Dogecoin, the original meme coin, recently marked its 12th anniversary on December 6, 2025, since its launch by Billy Ma...