For many of us, New York City is still the ultimate city. In the 20th century NY defined a new type of urban existence - the staggering verticality, the extraordinary mixing of people from all over the world, the extremes of capitalist wealth and dynamism. Still today, compared to sprawling megacities like Mexico City, or Shanghai, NYC remains a compact urban space. Its overlapping layers of architectural and infrastructural history, offer a “classic” experience of dense modernity, including unkempt dereliction, filth and infestation with rats. If you live in NYC you have a visceral sense of how plagues happen, and riots. Anyone who has lived there knows that the city seems to experience moments where huge masses of people seem to vibrate in synch. With powerful universities and media, it is an intellectually, culturally and politically vibrant place, capable of generating huge intensity of debate and true surprises.

In a city like NYC, one should expect the unexpected.

Nevertheless, it did come as a surprise, in the middle of the speech to the summer Davos meeting in Tianjin by Chinese Premier Li Qiang, to watch as hundreds of delegates turned to their phones to read the news that Democratic Socialist Zohran Mamdani had won the Democratic primary, making him the presumptive future mayor of New York, the headquarters global capitalism and the capital of the dollar system.

The causes of Mamdani’s decisive defeat of Andrew Cuomo are much debated. We should presumably start from the premise that this “upset” was, in fact, overdetermined. Cameron Abadi and I talk about some of the issues in a rather jet lagged podcast recorded shortly after the event.

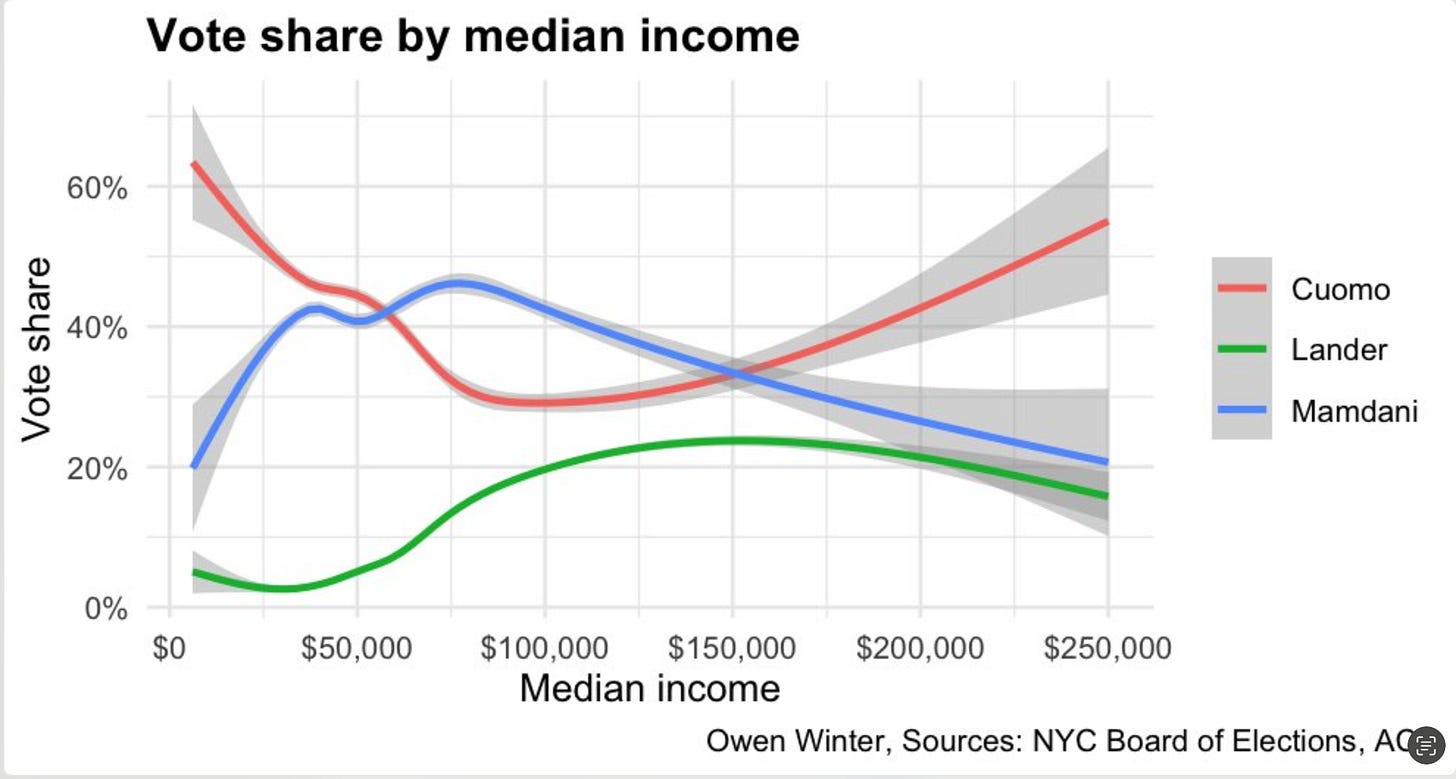

Mamdani is a brilliant candidate. He ran against a truly awful Democratic Party establishment. He has progressive, some would say radical, but obviously sane positions on everything from the subway to Israel-Gaza. The majority of the New York electorate and several of his rivals - kudos notably to Brad Lander - are smart and decent enough to acknowledge Mamdani’s sanity and to respond in kind. New York City is not a place that expects conformity. Mamdani ran on a progressive platform of measures regarding rents, taxes, public transports, childcare etc that address the palpable crisis of affordability in the city. Others will try to figure out whether it was Mamdani’s position on rent control that was decisive, as opposed to his position on Gaza. It does seem clear that Mamdani has rallied a new coalition that is heaviest in the “middle-income band”, which in NYC can be reasonably said to stretch from $60,000 to $150,000.

It is striking that he did less well in predominantly black neighborhoods of the city, which also, in many cases, are lower-income precincts.

What I want to focus on are the socio-economic structures of the city itself because knowing those may help us to understand what may come next.

New York City is a classic city also in its degree of socio-economic inequality. Even by US standards, it is a space of extreme inequalities of wealth and income. The concentration of that inequality within a compact urban space, creates a battlefield with more “classic” contours than the muddy mess of US national politics.

At the level of a city of New York, some of the classic tension between capitalism and democracy can still be felt. There was once a time when redistributive mechanisms could be built in America. The American income tax system is still progressive. There are basic structures of welfare. America has a public education system. But at the national level, since the 1980s, the traffic has been largely one way. The idea that democracy might enable the majority of Americans to proactively distribute significantly greater resources away from the rich towards public services and those most in need, has come to seem increasingly quaint. At this moment, Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill, a huge tax giveaway for the upper class, is moving through Congress. It will be profoundly regressive in its impact.

But within the frame of a city like New York, with a tightly packed population of 8.5 million, the distributional struggle takes on a rather different hue. In New York City the trade offs and conflicts feel real. The rich, the middle class and the poor cannot avoid each other, as they often do in the rest of the USA. Through shared infrastructure like schools or overcrowded and dangerous streets, the competition for scarce housing and the cost of everyday necessities, the struggle of competing purchasing power and class differentiation is played out in plain view. Meanwhile, the shocking state of the subway brings home viscerally the many failures of public policy. How can a city of such wealth be reliant on a system of such shabby, stinking decrepitude? It is not by accident that New York City’s upper class fear democracy more than their counterparts in much of the rest of the country. Here there might actually be a majority in favor or redistribution, major market regulation and against privatization. De facto, New York City’s taxing powers are limited. Mamdani is talking about a few percentage points for those earning more than a million dollars a year. Everything requires approval by Albany, the far more conservative state-capital, 140 miles to the North. But, to prevent these questions even being posed, the backlash against Mamdani will be intense and it will be very well funded.

That backlash will be led by big money from New York’s rich upper class. As the voting data suggest, his support dwindled fast amongst those with incomes more than $150,000. At the upper end, there are 28,000, or so, New Yorkers who filed income tax on adjusted gross income (AGI) of more than $1 million, accounted for 0.7% of all tax filers, 35.6% of the AGI, and 42.4% of NYC Personal Income Tax (PIT) liability. Roughly 4400 individuals declared more than $ 5 million or more. And 1600 made $10 million or more. That group, who amounted to 0.04% of the total returns in 2011-2021, accounted for 17.9% of the AGI, and 21.3% of NYC income tax paid. 123 people on the Forbes list of billionaires are registered as living in the city.

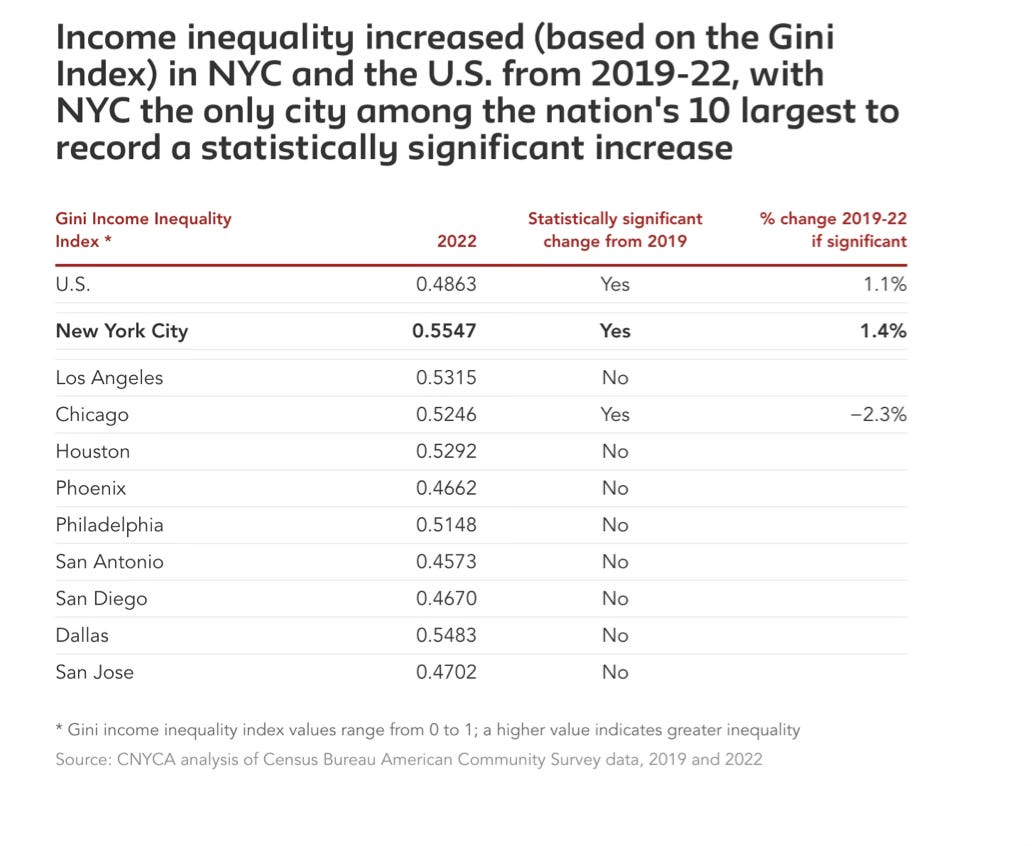

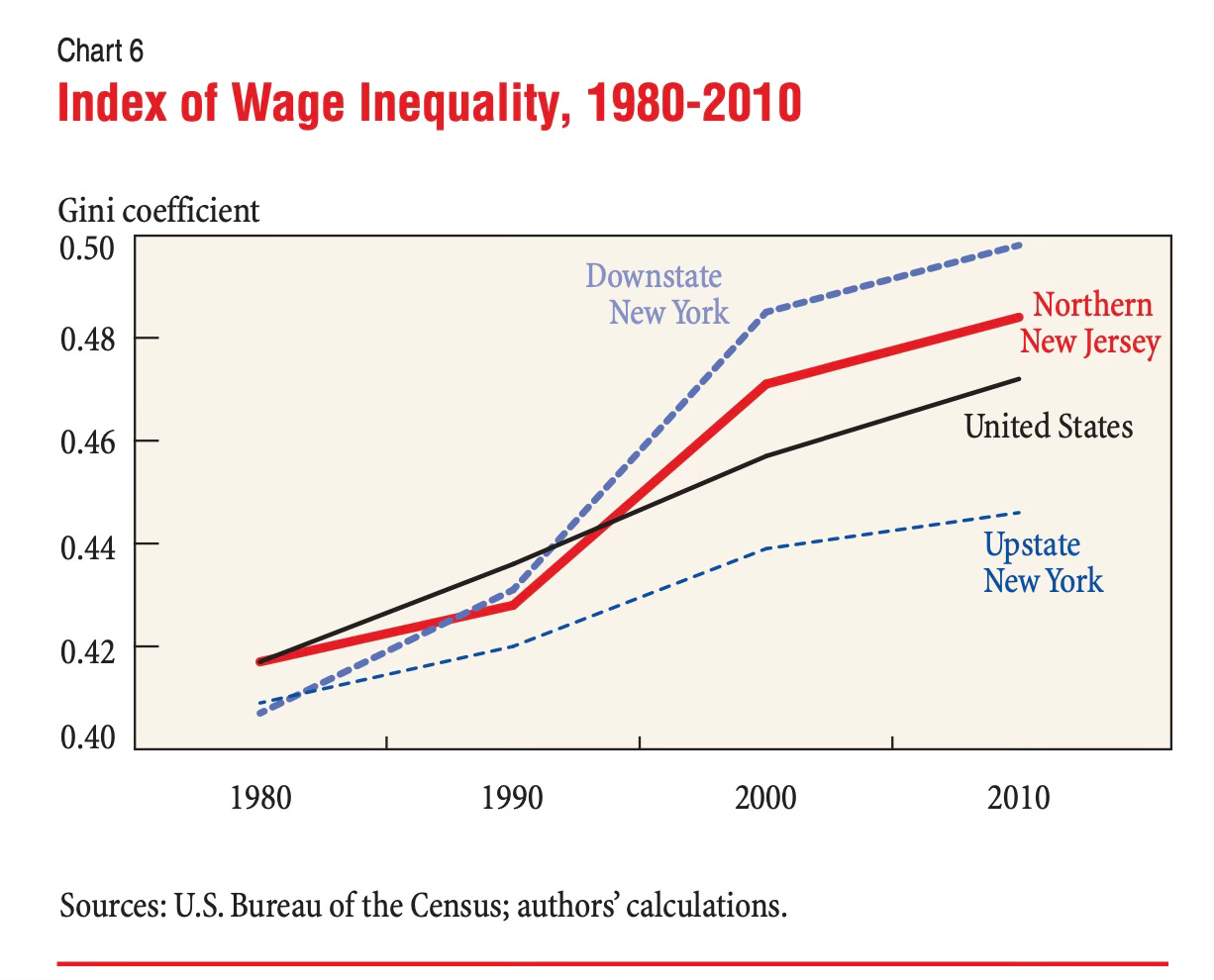

This upper class group are the tip of the mountain. The broader patterns of inequality are better captured by statistical measures such as the Gini coefficient, which describes overall patterns of disparity between incomes. In this regard New York City with a GINI coefficient of 0.5547 stands out starkly compared to all other American cities.

For sake of comparison, New York City’s Gini coefficient puts it on the same level as Rio de Janeiro (0.58). Germany’s capital, Berlin, has a Gini coefficient of 0.3.

New York City is overwhelmingly the most expensive place to live in the United States.

Source: Coli

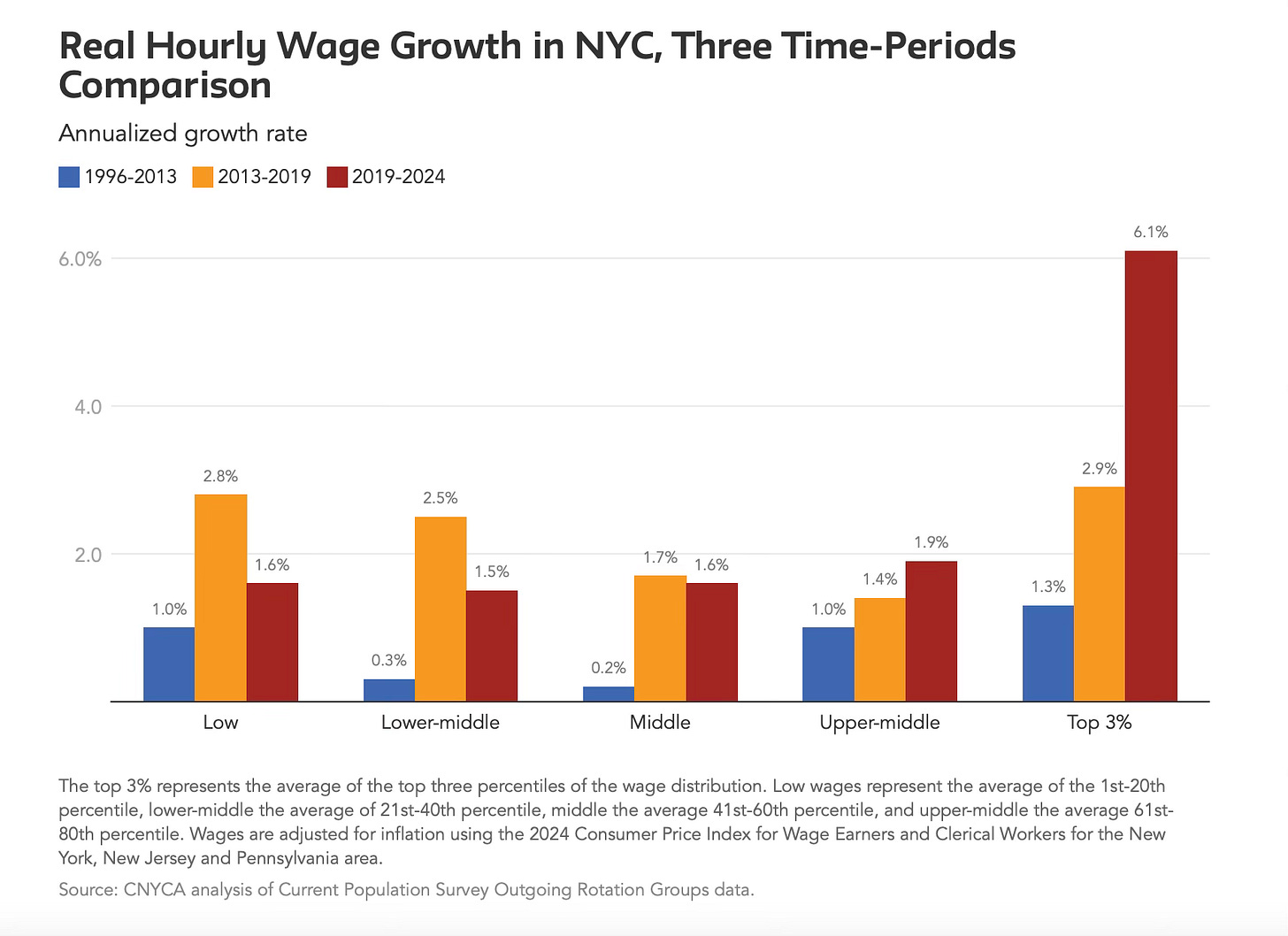

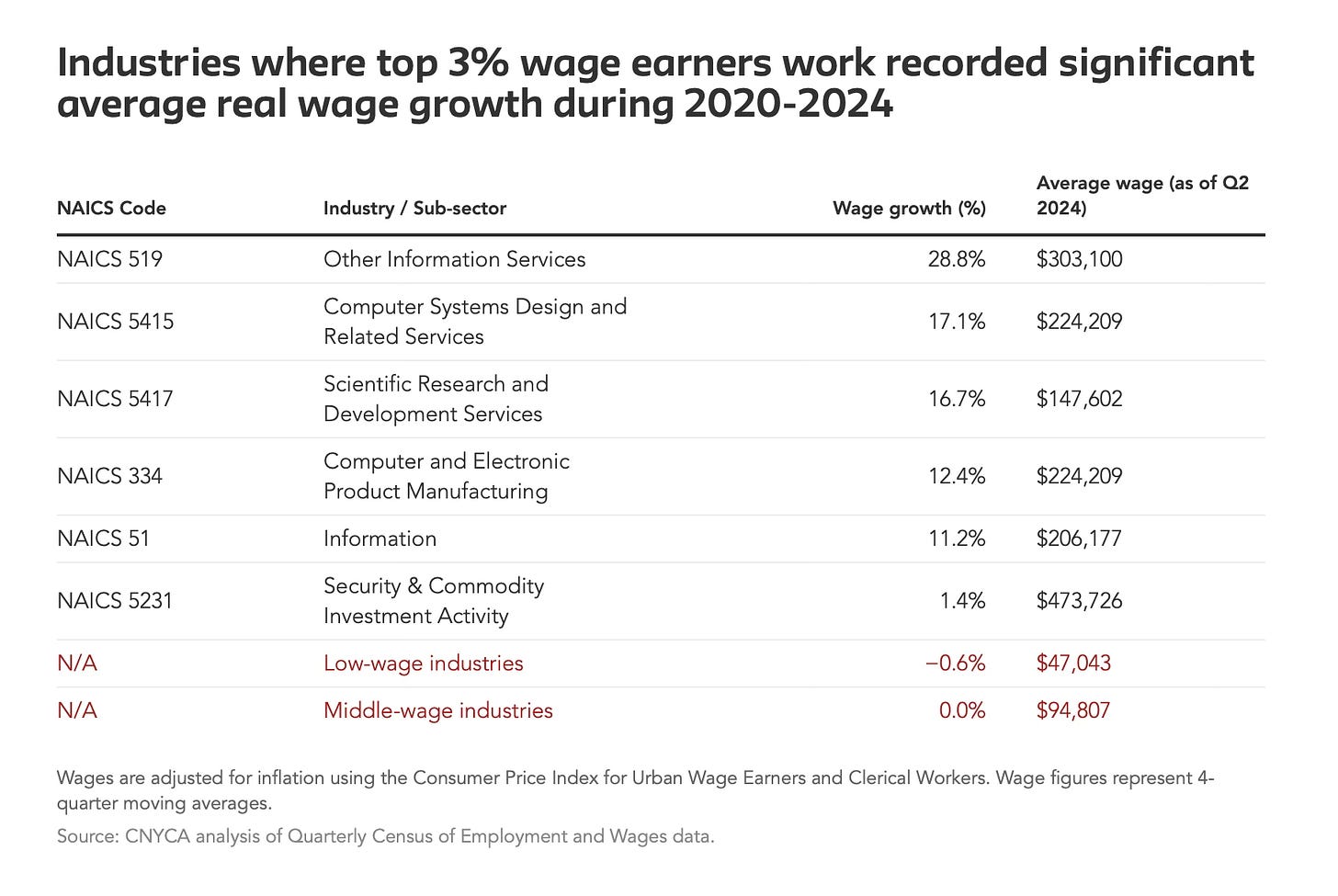

It is a city where since the 2010s polarization has not moderated, as it has at the national level, but has sharply increased. Those earning in the top 3 percent have seen their incomes soar away, whilst the rest of the population have seen increases barely in line with the cost of living.

Industries in New York where the highest paid are employed have seen substantial wage growth, whereas low-wages appear to have remained largely static. This divergence is so sharp that it causes a moment of disbelief!

Source: Center NYC Affairs

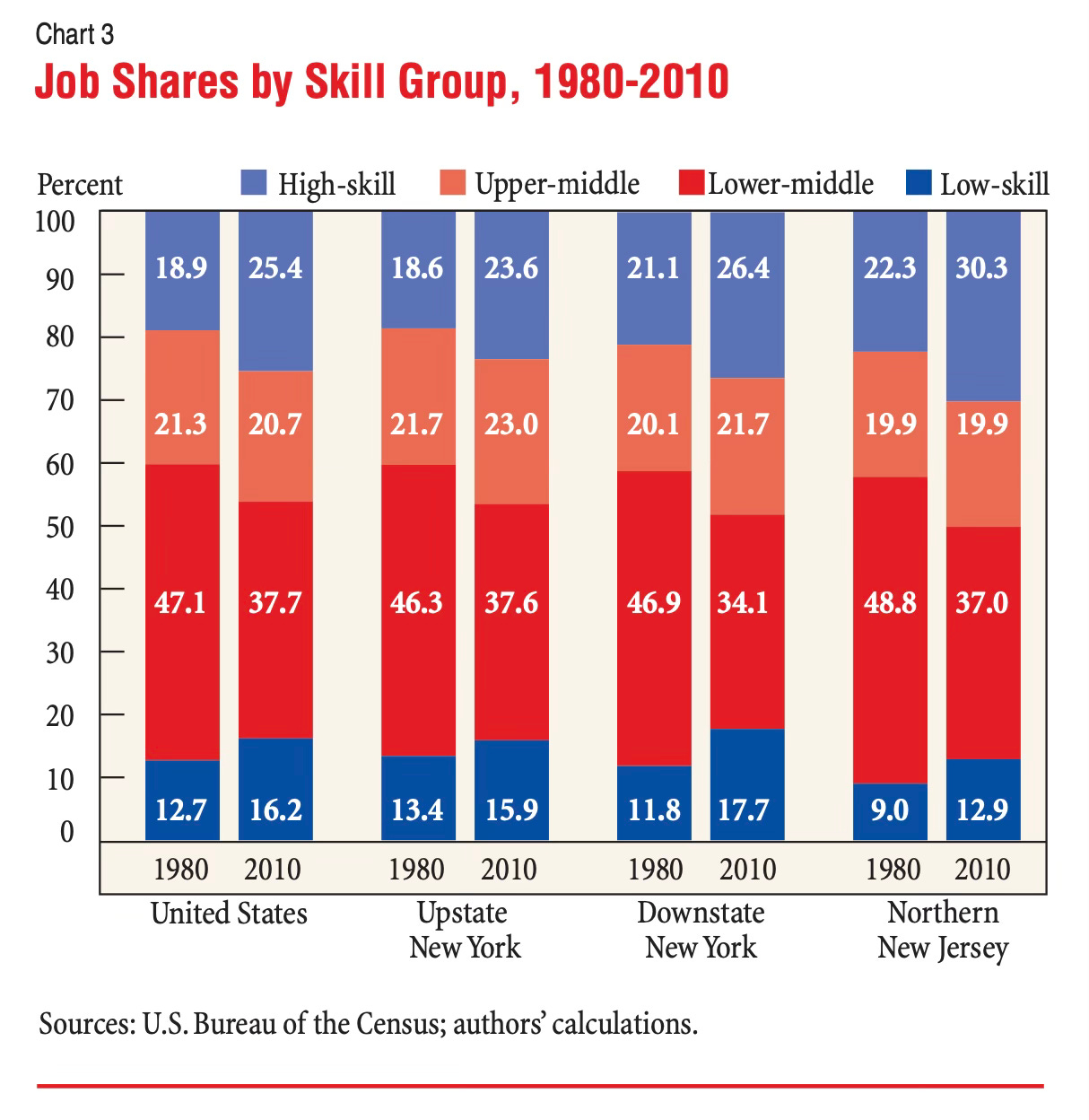

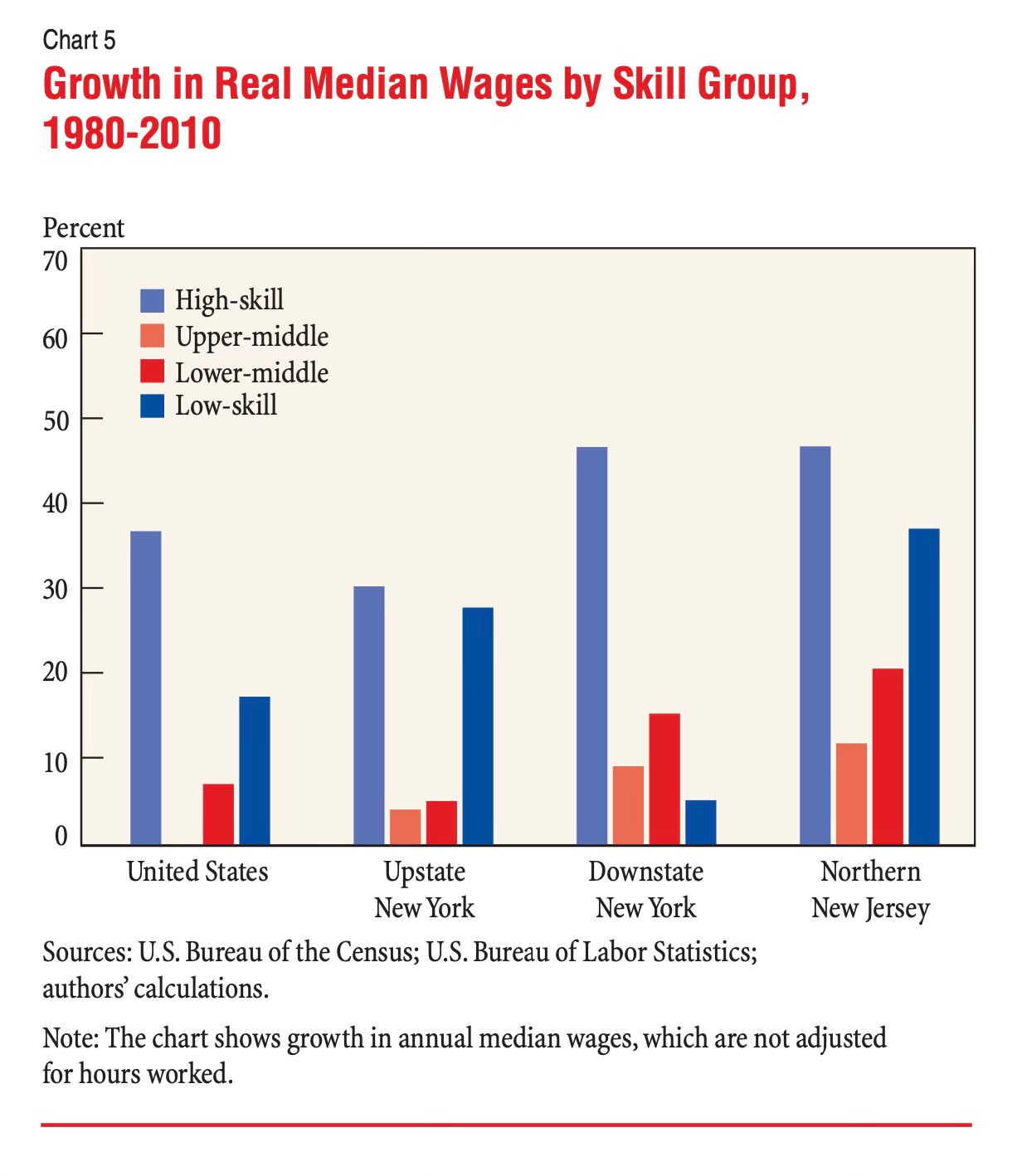

But, as work published by Abel and Deitz of the New York Fed confirms, these widening gaps reflect long-standing patterns of polarization in New York City and Northern New Jersey regions that amplify national trends to extreme levels. Across New York City and its immediate hinterland, high skill jobs have expanded, as have low-skill jobs, whilst mid-level jobs have been squeezed.

Source: New York Fed

Whereas wage growth for highly skilled workers has been above national averages, low-skilled workers in New York saw amongst the slowest growth in the country.

The net result is surging wage inequality. As recently as 1980 New York’s Gini coefficient was around 0.4. Today it is one third higher.

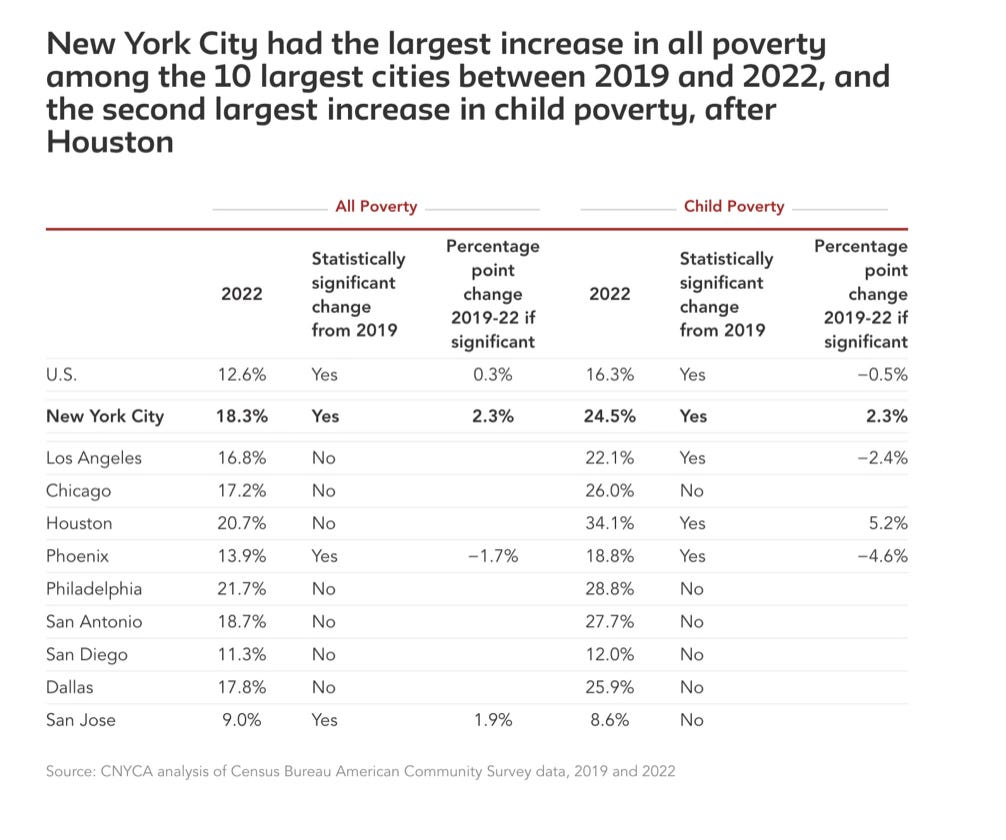

When you compress inequalities this extreme into a compact urban space, it would take city management of heroic excellence to avoid social and economic polarization. Regrettably, New York City is remarkable not just for its wealth. Roughly one fifth of the population is trapped in poverty.

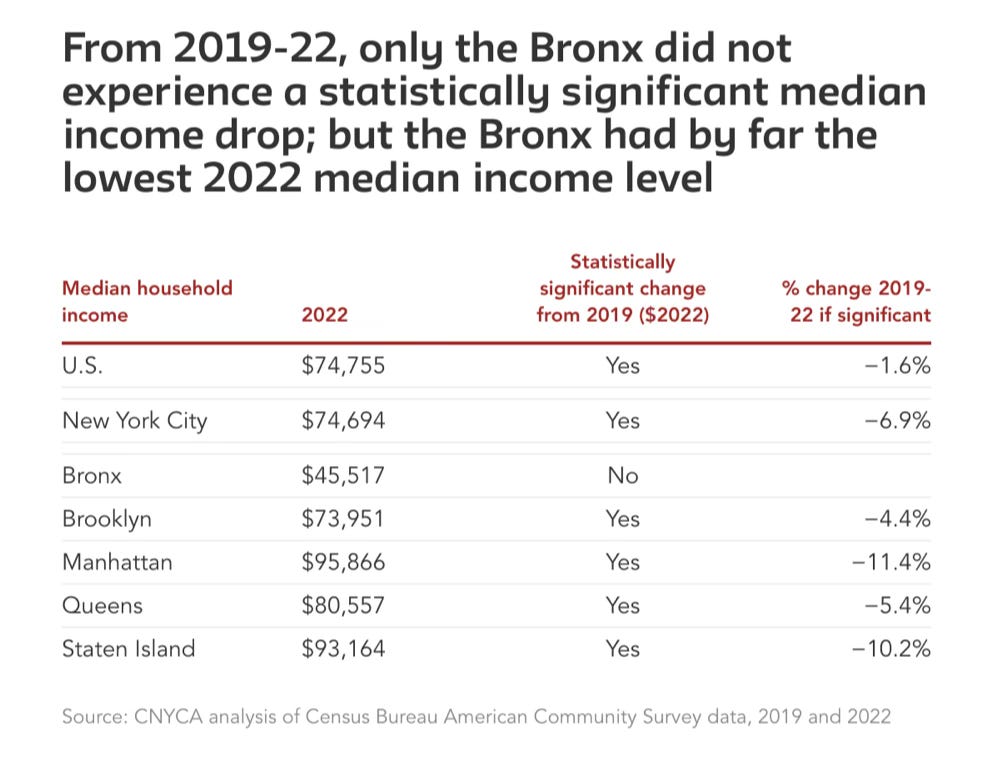

And New York City poverty is not borderline. The largest increase in poverty in NYC between 2019 and 2022 was amongst those in “deep poverty” which is defined as less than half of the federal poverty level. In 2022, the federal poverty threshold was $14,880 for a single person, and $29,678 for a four-person family with two adults and two children. In New York City, nearly 52 percent of the city’s poverty population of 1.5 million in 2022 lived in “deep poverty,” that is 750,000 people. Poverty affects entire sections of the city. In the borough of the Bronx, with a population of 1.4 million, the median income is $45,517, uncomfortably close to the Federal poverty line for a family of four. In 2022 New York City recorded a child poverty rate of just shy of 25 percent.

Source: Parrott Center for NYC Affairs New School

New York City remains hugely attractive to millions of people. But the gap between the resources of the vast majority of the population and the cost of living yawns increasingly wide. The city gets by. Its people are resourceful and resilient. But this coping comes at a price: increasing stress, resentment and incomprehension. How can things be this unaffordable, this dysfunctional and shoddy? Why is the city not as great as it could clearly be? Of course, a minority do extremely well. They feel no urgency for change. But for the majority of people the trends, both of recent decades and more immediately since COVID, are in the wrong direction. A politics that speaks openly about these pressures and urges bold and imaginative steps as Mamdani and the New York left do, is a starting point, both to address the issues and to relegitimize city government. His success is a rare sign of hope in American politics. If entrenched elites were to derail his candidacy in favor of machine interests, it would be a victory for privilege and a disaster for democracy that would resonate beyond New York.

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. I hope you find that it offers valuable insights, interest and provocation. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here: