BMC Public Health volume 25, Article number: 1527 (2025) Cite this article

The cancer burden in India is escalating, with rural regions facing the greatest challenges in access to early detection and treatment. Community Health Workers (CHWs), such as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), Village Health Nurses (VHNs), and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs), play a critical role in bridging these healthcare gaps. This study explores the barriers and contributions of CHWs while facilitating early detection and subsequent care in selected rural areas of India.

This qualitative study is part of the Access Cancer Care India (ACCI) implementation research project, conducted in three states: Rajasthan, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. We conducted six focus group discussions (FGDs) with 47 CHWs, representing various health cadres, to investigate their experiences and the barriers they face in delivering cervical, breast and oral cancer care. The discussions were analyzed using Charmaz’s Grounded Theory approach, with axial coding and constant comparative analysis until data saturation was reached.

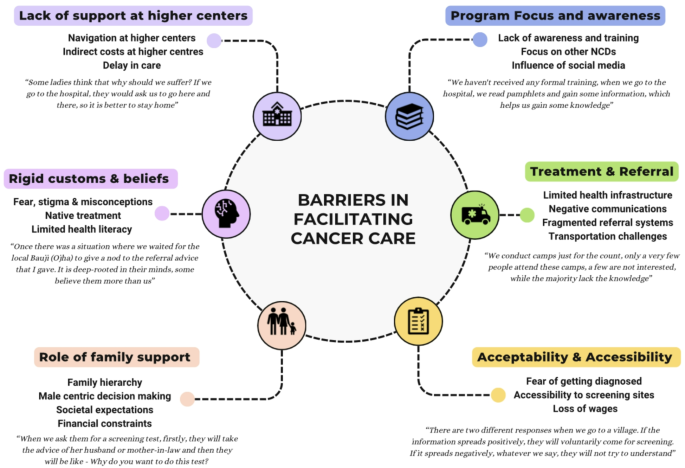

CHWs identified multiple barriers to cancer early detection and subsequent care delivery, organized into six overarching themes: (1) Program focus and awareness, (2) Treatment and referral challenges, (3) Acceptability and accessibility, (4) Rigid social customs and beliefs, (5) Lack of support at higher centers, and (6) Financial constraints. A lack of formal training, poor infrastructure, negative communication, fear of diagnosis, and financial burdens were among the major barriers highlighted. CHWs from Tamil Nadu and Kerala, where sporadic screening initiatives exist, reported better preparedness compared to their counterparts in Rajasthan. Additionally, the CHWs outlined the vital role of positive word-of-mouth and community engagement in improving cancer screening participation.

CHWs in rural India face significant personal, community, and health system barriers while facilitating cancer early detection services and subsequent follow up. Addressing these barriers through tailored training, enhanced health infrastructure, and community-based interventions can improve cancer care access and outcomes in rural settings. Future policies should focus on strengthening CHW-led approaches and addressing the systemic barriers in cancer care delivery.

The burden of cancer in India is escalating, with rising incidence and mortality rates posing significant public health challenges. According to the Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN), India reported an estimated 1.41 million new cancer cases in 2020, and this incidence is projected to increase sharply in the coming decades [1]. This burden is further augmented by the urban-rural disparities, with rural areas exhibiting distinct patterns, and experiencing poorer cancer outcomes due to accessibility, affordability of healthcare, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure [2, 3].

The intricate relationship between rural living and sociodemographic, lifestyle, dietary, behavioural, and environmental factors that influence screening participation, incidence, and prognosis often contribute to disparities in cancer care between urban and rural areas [4]. In addition, health literacy on cancer has remained low, especially in rural communities. This, when coupled with the lack of an organized screening program and limited access to effective treatment, often results in delays in diagnosis and poor survival outcomes [2]. While sporadic screening services for breast, cervical and oral cancers are available in rural India, they are rarely utilized due to various factors, including high costs and cultural barriers [5, 6].

With only 1.9% of gross domestic product (GDP) being invested in health, India’s healthcare infrastructure faces significant constraints [7]. The rural areas, where over two-thirds of the population live, are particularly affected. The rural population have access to only a third of the country’s healthcare resources [8]. Rural India’s public health care systems are structured into a three-tiered framework comprising of primary health centres, community health centres, and district hospitals, often needing to be more staffing and resources [9]. Poor road infrastructure, hilly terrain, limited public transport options, and lack of specialist care further impact access to cancer care in rural India. In addition, direct and indirect costs, including loss of income, travel expenses, and out-of-pocket treatment costs, further strain the financial burden of rural communities seeking cancer care [10].

Community Health Workers (CHWs), including Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) Village Health Nurses [VHNs] and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs), have been instrumental in helping to bridge some of the gaps in rural India. They often serve as key links between the community and the health system, functioning as primary focal points for health promotion activities and patient engagement [11]. Particularly in cancer care delivery in India, CHWs’ role is multifaceted and includes awareness generation, delivery of services, early detection and facilitation of referral to diagnostic and treatment services [12]. Despite their pivotal role, CHWs in India often operate with limited training, resources and support. This demanding workload, inadequate remuneration, lack of field support and other sociocultural and structural barriers often lead to burnout and attrition among CHWs, further compromising the delivery of cancer care services [13]. Thus, this study aims to explore the various contributions of CHWs, and the barriers they face in facilitating cancer early detection and subsequent care in selected rural villages of India. To get an overview of CHWs working in rural India, we selected rural health centres from three different states in India, namely Kerala (ranking first in Sustainable development goals [SDG] performance across the 28 states), Tamil Nadu (ranking fourth in SDG performance) and Rajasthan (ranking 14th in SDG performance). The selection of Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala as study sites reflects a deliberate strategy to capture diverse socio-economic, cultural, and healthcare system contexts, providing a valuable range of perspectives on implementing cancer early detection strategies. Despite the availability of similar studies, our study uniquely explores both the barriers and contributions by rural CHWs in enabling cancer early detection and subsequent care. Unlike previous research, it provides a comprehensive analysis across three different health systems in a LMIC like India, offering a nuanced understanding of CHWs’ experiences in diverse settings. By highlighting sociocultural, structural, and logistical challenges alongside enabling factors, this study adds an important piece to the puzzle of understanding the barriers CHWs face in delivering cancer care.

We conducted a qualitative inquiry as part of an implementation research project, Access Cancer Care India (ACCI), in Udaipur, Idukki and Villupuram districts of Rajasthan, Kerala and Tamil Nadu respectively. ACCI intends to develop and test multi-level strategies contextualized to the local health system for improving access to the early detection and care continuum for oral, breast and cervical cancers among rural population of India [14]. This qualitative exploration is one of the components of work package two [WP-2] of the project, which intends to explore various barriers faced by the general population regarding access to cancer early detection and subsequent care, and barriers faced by CHWs in facilitating the same.

A descriptive qualitative research approach was adopted to explore the various activities performed, training received, and the impact of social, physical and cultural barriers that influenced cancer early detection and subsequent care delivery. We embedded our research question on a social constructivist paradigm, with a relativist ontological position and a subjective epistemological stand [15]. We explored this research question with the assumption that the barriers and challenges faced by CHWs in delivering cancer care services are subjective and socially constructed.

We used the extension of the Health Behavior in Cancer Prevention Model by J T Gonzalez et al., focusing on the demographic, social support, and patient-provider relationship experience in explaining preventive cancer care utilization [16]. The model shows that the use of health services is affected by various barriers such as difficulties in accessing healthcare due to the environment, lack of social support and cohesion in communities, prevailing health beliefs, the perceived skills of healthcare workers, health locus of control, and health values. Since our qualitative enquiry also aims to explore the barriers using the same lines, we utilized this theoretical model to inform our exploration and developed a theoretical framework based on our findings. However, the final thematic analysis was conducted inductively, allowing themes to emerge organically from the data, reflecting the perceptions of CHWs rather than being strictly confined to the framework’s constructs.

The research teams at each study site conducted the FGDs between October 2023 to February 2024, whereby a single research assistant from each participating site conducted all the interviews. All three research assistants were females, two of them were clinicians (AA & VN) and the other was a laboratory assistant (HP). All research assistants received the necessary training [interview techniques, conduct of interviews, note taking, transcription and coding fundamentals] on qualitative research from the research team [AC, IK] through a face to face training followed by a dedicated session online, before conducting the interviews. A note-taker and a moderator [to facilitate the discussion] were present without participating and noted all the discussions. The entire team established rapport with the participants well in advance [by introducing the team and the objectives of the study]. The FGDs were coded and analyzed by SP and KT (with adequate training in qualitative research and coding). SP and KT are public health experts not directly involved in the provision of cancer care at the sites; hence, their perspectives bring a different dimension to the analysis.

Tamil Nadu has an ongoing government-run facility-based opportunistic cancer screening program for cervical, and breast cancer since 2012 and an oral cancer screening program from 2017. Apart from this, an organized community-based cancer screening program has been conducted by the participating institution since 2015. The state of Kerala had sporadic cancer screening and early detection campaigns arranged by the participating institution in specific sites. However, the situation of CHWs in Rajasthan was different as the target area did not have any cancer screening activity. Thus, we were able to capture the perspectives of CHWs working in three unique healthcare environments.

To capture the ground-level barriers the CHWs face in facilitating cancer early detection and subsequent care, we conducted six focus group discussions [FGDs, two from each site]. Particularly in TN where a cancer screening program existed, the first FGD was conducted involving CHWs from the public sector who were involved in imparting cancer awareness at the community level and opportunistic cancer screening services at the facility level. The other FGD was conducted involving the CHWs from the participating institution, who conducted an organized community-based cancer screening program. This was pre-planned to understand the challenges faced by CHWs from two different settings facilitating different modalities of cancer screening services. We approached the primary health centres’ medical officers to obtain the CHWs list. The research team identified CHWs suggested by the medical officers, sought consent, and reached out to the rest through the snowballing method. From the proposed list, the CHWs were identified with an inclusion of individuals who were working under the PHC/institution from the same location, had at least 2 years of experience in the field, and spoke the native language. We captured their referral practices, their current roles and responsibilities, working patterns, and barriers they perceive while facilitating early detection and subsequent care. Since, TN had an established system of cancer screening and NCD nurses were instrumental in delivering the services in the community, we also included four NCD nurses in order to capture the scale of activities performed on cancer screening. These NCD nurses were chosen purposively; three from the government and one from the participating institution in one of the FGDs conducted among the TN CHWs. In this paper, we present the contributions of these NCD nurses to cancer early detection separately. However, we do not delve into the specific barriers they face, as their experiences offer a distinct perspective from that of CHWs, which remains the central focus of this study.

We obtained ethical approval from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IEC 2205) and all participating institutions. Regulatory approvals were sought from the Health Ministry Screening Committee (HMSC) of the Government of India (2022–17547) before commencing data collection. We informed all FGD participants about the study’s objectives and obtained a written informed consent. Participation in the FGDs was entirely voluntary, with no compensation or incentives provided to the participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The FGDs were conducted in a location and time convenient for the study participants in the local language (Tamil, Malayalam, and Hindi). We used a semi-structured interview guide to facilitate our discussion. The core research team [AC, IK] developed the interview guide and conducted face validation with other investigators to ensure clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness. However, the guide served as a flexible framework, and the interviewers were encouraged to conduct the discussion in free flow if warranted (Supplementary). We obtained permission from all participants to audio record the discussion. Each discussion lasted for 45–60 min. Only the participants and investigator team were present during the FGDs. The research team used probes as necessary to enhance the discussion. The site research team prepared a verbatim transcript [In Hindi, Tamil and Malayalam], translated it into English, and back-translated it to ensure consistency. The final English version was shared with the coding team [SP & KT].

Charmaz’s Grounded Theory approach principles were utilized to analyze the data, including axial data coding, constant comparative coding, and theoretical sampling until theoretical saturation [17]. Once the transcripts were shared, SP initially read them several times in detail to familiarise with the data. Later, the critical statements in the transcripts were coded, followed by axial coding and theme development. KT did the same independently: compiling emerging codes and categories in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Wherever both disagreed, the consensus was achieved through arbitration. We used a constant comparative approach at each level of coding to check if the emerging code is related to the other codes in this axis. Since some of the barriers identified reflected the community’s challenges in assessing cancer early detection and subsequent care, we planned to view these community-level barriers using the CHW’s lens during the mobilization process. Data saturation was determined through an iterative process involving continuous review and theme monitoring. By the sixth FGD, we noted redundancy in responses indicated thematic saturation, as no new concepts or codes were identified [18].

We conducted these discussions among the grassroots-level CHWs involved in cancer care delivery and early detection services. Efforts were taken to ensure that the purposefully sampled CHWs represented the sites belonging to different health cadres in service delivery. This helped us obtain adequate transferability of the findings. At the end of every FGD, we presented a discussion summary to the participants for validation and to improve the credibility of our findings. We maintained detailed notes of the entire interview process to ensure dependability. We attempted participant, data source and investigator’s triangulation to ensure confirmability.

In total, we collected information from 42 CHWs (Mean age 38.8 [7.5] years; 39 females and 3 males). The cadre of health workers who participated included VHN and Women Health Volunteers (WHV) from TN, ASHAs from KL, ASHAs and ANMs from RJ, involved in delivering various healthcare services across the selected rural villages. Other characteristics of the study participants are described in Table 1. All transcripts captured detailed descriptions of different activities the CHWs performed and offered in-depth insights into the barriers they encountered while facilitating cancer early detection and subsequent care. The various barriers were organized into six overarching themes. We used the thematic analysis approach using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) to derive at the final six themes [19] (Fig. 1).

We documented the diverse activities performed by CHWs in facilitating cancer early detection and subsequent care across selected rural communities, observing notable disparities in the scope of services delivered. In TN, where cancer screening program is relatively established, CHWs conducted cervical, breast and oral cancer screening, playing a vital role in the referral pathway and actively following up individuals. Most of the interviewed CHWs from the participating institution and the government CHWs were trained, confident in undertaking screening, and well-informed on the signs and symptoms of cancer. CHWs from the participating institute enumerated eligible populations through door-to-door surveys, invited eligible individuals to participate and had specific referral mechanisms. CHWs from the government were primarily involved in imparting cancer awareness in the community and mobilization for cervical, breast and oral cancer screening at the facility-based NCD clinics. They were also involved in conducting awareness and screening camps, and ensuring follow-up care. CHWs from both sites had strong networks with local community-based organizations to widen service delivery. In KL, although most CHWs were aware of cancer screening, only a few had received specialized training for cancer screening. They were able to create awareness and play a role in the referral pathway of cancer patients. These findings are reflective of the choice of study sites: TN [a catchment area linked with the tertiary cancer care provider] and KL [a hilly terrain]. In RJ, where the cancer early detection efforts are still developing, CHWs had limited knowledge of cancer, lacked formal training, and faced several sociocultural barriers. The CHWs here perceived the need for structured training to understand better and navigate the cancer care pathways. However, a few CHWs were involved to an extent in assisting patients in navigating tertiary centres, helping with transportation, and making follow-up calls to ensure that patients understand what has happened during their referral and what the next steps are.

NCD Nurses in TN play a crucial role in screening, awareness, and referral for breast, cervical, and oral cancers. They educate women on breast cancer symptoms and encourage self-examinations, referring those who require further evaluation. They conduct clinical breast examinations (CBE) for breast cancer screening and perform Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) for cervical cancer screening. Their responsibilities include initial patient assessment, referral to doctors for confirmation, and guiding patients to higher medical centers for further care. Additionally, they organize screening camps and awareness programs to enhance community participation.

Most CHWs expressed a gap in their knowledge of cancer warning signs, and a lack of formal training in cancer early detection, except CHWs from Tamil Nadu and Kerala, where screening initiatives for breast, cervix and oral cancers have been implemented.

“We accompany the staff nurses and doctors to VIA camps. As field workers, we assess the patients at that time. We also observe and learn, and classes are conducted for us then. But it would be helpful if they give separate training for this” [VHN, TN].

“We received training during the recent ASHA meetings to conduct breast examinations and to identify white patches in the oral cavity”. [ASHA, KL – where the screening activities are in place]

“We haven’t received any formal training, when we go to the hospital, we read pamphlets and gain some information, which helps us gain some knowledge”. [ASHA, RJ]

CHWs perceived that there is a lack of prioritization towards cancer in the existing healthcare system, with emphasis placed on other non-communicable diseases such as hypertension and diabetes over cancer.

“No camps are organized regarding cancer. No one has come for a meeting to give information regarding cancer. Like we know everything about Tuberculosis and other NCDs. We have even done slogans and posters on them” [ASHA - RJ].

The CHWs highlighted the persistent influence of media advertisements where celebrities promote pan masalas [A mixture of areca nut with slaked lime, with or without tobacco] [20] which encourages the younger generation to begin using these harmful products.

“Firstly, the big advertisements should be stopped. If the advertisements stop, the consumption will decrease. Celebrities should stop acting in them. They advertise, people learn and consume” [ASHA, RJ].

The CHWs observed that many primary health centres lack essential infrastructure, including equipment, adequate privacy, and staff trained in cancer screening, leading to a loss of confidence in the local health system.

“No programmes are running, no camps are organized regarding cancer. Cancer is spreading in the villages, people are getting diagnosed with cancer, they are taking treatment from Bauji (Ojha – local faith healer), but we do not have medical knowledge” [ASHA, RJ].

“ASHAs don’t have any role in screening and we do not get any training for screening. There are no cervical cancer screening facilities in our centre”. [ASHA, KL]

CHWs noted that in rural villages, cancer screening participation is strongly influenced by word of mouth. Positive information motivates people to attend screenings, often encouraging others to join voluntarily. However, negative rumours can lead to widespread resistance, making it difficult for CHWs to convince people to participate, despite their ongoing efforts.

“There are two different responses when we go to a village. If the information spreads positively, they will voluntarily come for screening. If it spreads negatively, whatever we say, they will not try to understand. Some people, even if they are eligible, say that - I’m good and I don’t need the test”. [WHV from the participating institution, TN]

“Some people will come for screening and tell others that it is better to get checked and ask them to get tested. But if they say negative things like we are doing this and that, they say we ask them to adjust their clothes for examination and spread false information, making people say we will not come” [WHV from the participating institution, TN].

CHWs emphasized the difficulties in tracking patients they refer for further care. Most referred patients only visit higher- district level hospitals if they have symptoms, often preferring local doctors they trust over travelling to distant hospitals. Even when patients follow the referral and visit nearby first referral points, the lack of necessary services discourages them from returning for follow-up. Repeated referrals that don’t resolve the patient’s healthcare needs erode their confidence in local healthcare facilities.

“If every time, when they reach the referred centre, and they refer to another place, people will slowly lose interest in the local hospitals (Community health centres [CHC] and primary health centres [PHC], and there will be no meaning of having a CHC or PHC there” [ASHA, RJ].

“If we refer screened individuals through our PHC NCD staff, only then, we can follow up directly. So, we ask the patient to go to our PHC. If we ask them to go to Government Hospital directly, we don’t know whether they will go, and we cannot follow them” [Government VHN, TN].

Transportation poses a major challenge, particularly in areas with poorly constructed roads. CHWs often rely on local assistance or government ambulance services to transport patients. Reaching remote or hilly areas at odd hours can be daunting.

“Some live in hilly areas, some even in forest areas, so going to their homes can be a bit intimidating and we feel afraid to go there but, we take someone with us if we are going to distant villages. Sometimes we borrow other’s vehicles to reach there” [ANM, RJ].

CHWs noted that many women deferred screening due to fear that it could result in a cancer diagnosis, leaving them uncertain about how to proceed.

“Some women are scared that after the screening, we might tell them that they have cancer. After that, what can we do?” [Government VHN, TN].

CHWs often walk long distances and wait for women to return from work to render services. Despite their efforts to educate and persuade, many women remain reluctant to participate.

“We have to go far, I had to start by 4 am [refers to an incident where he had to bring a screen positive from a rural area to the referral centre], we have to walk to reach people, and we need to talk to women. We need to wait for hours if there are several of them. There were no public buildings or offices to conduct the camp [refers to a camp they conducted in a forest area], and facilities were not suitable for the people to come and do the test. Some women agree while others do not, and some may not agree at all on screening. If they don’t agree, there’s not much we can do. [WHV from participating institution, TN]

Many screen-positive individuals are hesitant to seek follow-up care at higher centres due to the potential loss of wages. Most of them prioritize work over medical appointments since they are responsible for supporting their families. CHWs find it challenging to convince them.

The majority say “I have a family to support, and children to feed. If I go to higher centres, it takes one full day, sometimes even more! I cannot keep losing my wages, if I take off continuously, I might lose my job!”[ASHA, KL].

Convincing individuals from rural settings to participate in health screenings poses considerable challenges for CHWs, including reluctance, limited understanding of the benefits, and competing priorities. Persistent efforts, multiple contacts, and community education were essential to improve participation.

“Some educated people, even if we explain, are unwilling to undergo screening. They say - We are healthy now, don’t create unnecessary fear. Some stubbornly say that if anything happens, we will take care of it, and you need not worry”. [VHN from the participating institution, TN]

“Some people say you are asking me to remove the blouse; I don’t like it. If I had known it before, I wouldn’t have come. They told me this and went back [WHV from the participating institution, TN].

CHWs highlighted the critical role played by family hierarchy in health-seeking behaviour. In many instances, as narrated by the CHWs, a woman’s health-seeking behaviour was strongly influenced by family dynamics. Women often prioritize family responsibilities and childcare over their health. However, the CHWs have recently observed a positive shift, as more women are becoming financially independent and educated. With greater autonomy, they are increasingly empowered to make their own healthcare decisions, including the choice to undergo screening.

“When we ask them for a screening test, firstly, they will take the advice of her husband or mother-in-law and then they will be like - Why do you want to do this test? Out of 100 females, only 50% will go for cancer screening tests” [ASHA, RJ].

“Nowadays, women don’t wait for their husbands’ permission; their decisions are based on their interests” [VHN from the government, TN].

In rural settings, male-centric decision-making still influences women’s access to healthcare. Even when a woman is willing to undergo screening, following the CHW’s advice, her decision is frequently shaped by the influence of elder family members, whose approval or opinions often carry significant weight in the final choice.

“In some cases, even if the patient is willing to come for the treatment, their husband and children will not be interested and will ask - who would cook for us? So, they never follow up on the treatment. Sometimes, even we are questioned! Their family members will ask us if you take them to the hospital, who will do the work for us” [VHN of the participating institution, TN].

In rural areas, women conceal their health issues from family members due to shame, leading to delayed treatment, especially for conditions like cervical cancer. Older individuals face additional challenges; they may resist treatment due to a lack of support and a sense of abandonment, questioning the value of continued care. This reluctance creates significant obstacles for health workers attempting to encourage timely medical intervention.

“When it comes to women, they don’t want to disclose their disease-related issues because of feeling ashamed of society. She is reluctant to even go to the hospital, they tend to keep them hidden and thus the progression of cervical cancer starts slowly” [ASHA, RJ].

“People of this generation would listen to us and take the next-level approach. However, asking the older generation to take the treatment is very difficult. They would ask us, “Why should I live and I don’t have any companion to take me for further treatment?” Yes, They say - “Nobody is with me now. If anything happens, there is no problem for me. Why do I want to take treatment?” They avoid us and do not listen to us”. [Government VHN, TN]

CHWs frequently encounter situations where patients’ inability to afford treatment becomes a major barrier to their own role in ensuring timely care. CHWs shared multiple anecdotes where patients had to borrow and take loans to support the cancer treatment from their family members.

“Cancer treatment can be expensive, and if someone doesn’t have money, they often seek financial help from neighbours, friends, or family members. It’s not easy for them to afford the costs associated with cancer treatment”. [ASHA worker, RJ]

The stigma around cancer screening is deep rooted among rural women, often driven by fear, misconceptions, and cultural beliefs. CHWs elaborated extensively on the sociocultural barriers they faced in the field, highlighting the scale of misconceptions and stigma that prevail. Many rural women associated cancer diagnosis with shame or hopelessness, leading to reluctance to seek care. Additionally, CHWs also highlighted that women were concerned about privacy, and believed that cancer is communicable and incurable, and they often conceal their health issues due to societal shame, and a few still think cancer is due to the “wrath of god.”

“I would like to say that people have misconceptions; if they are suffering from any disease, they will not tell anyone because they believe that if they inform others regarding their problem, they will get caught in the devil’s eye and their problems will increase further [ASHA, RJ].

“I know a lady who was diagnosed with cancer in the uterus, she was advised to undergo uterus removal. The lady was willing to undergo the procedure, but the husband wasn’t. The reason the lady mentioned was ‘My husband feels that - If my uterus is removed, He doesn’t have any use with me. My life is gone now - she added’ [ASHA, KL].

CHWs underscored the significant role of local faith healers and the community’s belief in traditional treatments, particularly in RJ. CHWs mentioned that for most non-specific complaints such as stomach pain, and white discharge or bleeding per vaginum, community members often reach out to local healers (Bauji) instead of receiving proper medical care. They even recalled situations where the local community members waited for the “Bauji” to approve their recommendations.

“Once there was a situation where we waited for the local Bauji (Ojha) to give a nod to the referral advice that I gave. It is deep-rooted in their minds, some believe them more than us. Once in our village, there was a case of exorcism, one person’s mother was diagnosed with cancer stomach, so went to the local Baba, prayed, and performed some rituals. Awareness is the key! [ASHA, RJ]

The CHWs noted that local communities are often unaware that cancer screening is available free of cost, and several government schemes [Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme in TN, Karunya Arogya Suraksha Padhathi in KL, Chiranjeevi in RJ] are in place to cover most of the medical costs incurred during cancer treatment.

“Many people tell us, that if we visit the big hospitals in cities for treatment it would cost in lakhs. Thinking like that, people even don’t take steps to seek treatment. They are not aware of the ongoing government programmes from which they could benefit, We try our best to educate them. [ASHA, RJ]

The biggest challenge that CHWs face during the cancer early detection and subsequent care pathway lies in navigating a referred patient across the referral pathway. They recounted instances where the referred patients felt lost in the overwhelming crowd at the tertiary care centres. It was more particular among rural women, who often need more familiarity with hospital admission, administration and laboratory procedures and their locations inside the hospital. Fear of inadequate and delayed care, particularly in the absence of a support system, further deter the patients from seeking treatment. Social workers often face logistical and financial challenges which worsen health disparities in rural communities despite their efforts to support and guide patients.

“There was one lady who was screened positive for cervical cancer and referred for follow-up. She didn’t even know where is the nearest referral centre and had no one to take her. There is very little guidance for her in the tertiary care centres, she doesn’t know where is the OPD, where to register, or where to go to give a sample. She came back, seeing the wrong physician for a random complaint. Thus, nowadays, whenever our doctor refers old female patients who are sick or uneducated, we would take the help of male social workers. Brother (refers to the male social worker) had to start early in the morning., travel 165 km, be with them throughout, and drop them back at the village by night. We try to help in every possible way, but we too have a family and it’s becoming very difficult” [WHV from participating institution, TN].

“Some ladies think that why should we suffer? If we go to the hospital, they would ask us to go here and there, so it is better to stay home” [WHV from participating institution, TN].

CHWs touched on the impact of indirect medical and non-medical costs (such as transportation, loss of wages, accommodation and food costs) on health-seeking behaviour. They added that the local governments have established several insurance schemes to cover most of the direct medical costs. However, indirect costs incurred by rural patients while accessing cancer care, are beyond the spectrum covered under the schemes. CHWs narrated instances where the poor village men and women had to forgo their wages, spend on transportation, and spend on food and lodging after reaching the tertiary care centres. These expenses are doubled when they have an accompanying person. CHWs often reckon these issues before making a referral. Sometimes they had to share these indirect costs [mainly the transportation and food costs] to help them.

“From investigation, money for food, and bus, we will all share, and this is done only for positive patients who couldn’t afford. Even after going home, we will call them to check if they have gone back safely, sometimes even at 10 pm”. [VHN from participating institution, TN]

“We refer patients for their good, but the next question we face is – “Who will pay for our transport, it’s very far from here, and if I take my relative with me, I have to pay for their food and stay. Do you know how difficult to get a lodge near such big hospitals and how costly it is? Sometimes, we feel instead of spending money on these, we can seek local treatment here”. We feel sad for them. [ASHA, KL]

CHWs elaborated on the health system delay that the referred patients face. These delays often stem from overburdened healthcare facilities and complicated navigation processes.

“We refer patients, sometimes, they roam there at district hospitals the whole day, not knowing what to do and return without getting treated. We cannot blame the doctors there, they are overburdened, there should be someone to guide the referred patients” [WHV from participating institution, TN].

This qualitative study explored various contributions of rural CHWs in facilitating cancer early detection and subsequent care in India, with a particular focus on the barriers they faced during the process. Our analysis uncovered six major themes: (i) Program focus & awareness, (ii) Treatment and referral, (iii) Role of family support (iv) Acceptability and Accessibility (v) Rigid Customs and Beliefs, and (vi) Challenges at Higher Centers. The findings from our themes two, three and six, which focus on individual level and health system barriers, align with earlier qualitative evidence from LMICs. These studies highlight inadequate health infrastructure - characterized by unclear roles and responsibilities, suboptimal and fragmented referral systems, and shortage of human resources at higher centres - as key drivers of inconsistent cancer care delivery [21, 22]. The socio-economic and community-level barriers identified by our study also resonate with findings from other studies published in India [13, 23]. and other LMICs [24,25,26].

The CHWs in Tamil Nadu (TN) and Kerala (KL) demonstrated a considerable level of involvement in cancer screening, which was in contrast with findings from Rajasthan (RJ), where CHWs had limited engagement in cancer care due to a lack of training and awareness. The CHWs across the selected sites adopted multiple roles—ranging from health educators to patient navigators—depending on the needs of the local population and what the local health system could provide. Such capacity to dynamically adapt roles aligns with the community health worker model observed in other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [27,28,29,30]. The success of cancer care activities across TN and KL showcases the need for organized cancer screening programs and strong political commitment. The disparities across the three states also highlight the need for site-specific localized cancer training and capacity-building initiatives to enhance the role of CHWs in cancer care across different regions of India.

Our findings emphasize that the barriers faced by CHWs are not always solely rooted in the health system but are also shaped mainly by prevailing cultural and societal norms. Previous literature from other LMICs suggests that a lack of awareness and cultural beliefs could significantly hamper cancer prevention efforts [31,32,33]. In our study, CHWs also highlighted the influence of male-centric decision-making in rural households, which often limits women’s access to healthcare. This patriarchal structure and social hierarchy within families, not only affects women’s autonomy in seeking care but also complicates CHWs’ efforts to promote cancer screening [34, 35]. As noted in the narratives, the access-related barriers not only result in delays in cancer care but also force the rural communities to choose alternative treatment options that are locally available. These are further compounded by a lack of family support, stigma, religious beliefs and financial constraints [36,37,38].

The health systems barriers, such as limited infrastructure and fragmented referral systems, identified in our study are not specific to India; rather, they are common to many LMICs [39,40,41]. According to the CHWs in our study, the community trust in the healthcare system is weakened by a lack of facilities at the local PHCs. Thus lack of trust, when coupled with negative communications, results in poor participation in screening programs. Furthermore, the fragmented referral pathways, where people lose track after being referred, underscores a critical gap in the continuum of cancer care. The disintegration of various levels of health care, particularly between primary and tertiary care centres, alongside transportation challenges and delayed care at higher centres, adds another layer of difficulty for the CHWs [21, 42].

The fear of getting a cancer diagnosis is often rooted in the perception that cancer is an incurable and costly disease. Economic constraints had always remained a significant barrier that influenced health-seeking behaviour, as highlighted by a previous study from India [43]. Many rural families find cancer treatment financially inaccessible due to the indirect expenditures associated with it, which include transportation, food, and housing [44, 45].

While a few reported barriers may reflect the challenges faced by the general population, they were included since these factors directly impacted CHWs’ services—particularly in referring and convincing patients for early diagnosis, resulting in unsuccessful referrals. Since CHWs’ experiences were inherently shaped and interconnected with the barriers faced by the communities they serve, maintaining these reflections in our analysis was essential to accurately represent the real-world difficulties CHWs encounter while facilitating cancer care. Establishing trust within the community was essential for overcoming the barriers identified by our study. CHWs represent a vibrant workforce identified from the community, who when trained, could be instrumental in delivering several health services [46]. They often serve as the community’s first point of contact for several issues [47]. Our findings suggest that positive word-of-mouth can significantly enhance participation in cancer screening. This underscores the importance of community engagement strategies and tailored interventions that would influence decision-making [48, 49]. Thus, effective community engagement warrants a multipronged approach, including a range of stakeholders such as local leaders, religious figures, and other influential members of the community who can help us shift perceptions. The success of such community-based strategies has been documented to improve several health outcomes in various other settings [50, 51].

Our study has several implications at various levels of cancer care delivery:

Firstly, there is an urgent need for comprehensive and continuous training programs for CHWs who are highly motivated to improve their provision of cancer care. In addition to technical aspects, such training, we should also prioritize communication skills, cultural competence, and strategies for overcoming stigma. Furthermore, it is imperative to integrate CHWs into the existing referral and follow-up mechanisms. This could entail streamlining referral processes, enhancing coordination between various levels of health care, and making it more transparent and sustainable [45].

From a policy perspective, our study emphasizes the need for targeted interventions to address the barriers identified at the community and health system levels. Policies should prioritize strengthening the healthcare infrastructure, ensuring that primary health centers (PHCs) are equipped with the necessary staff and resources to conduct cancer screenings. Policymakers should consider community engagement in health promotion activities. Any intervention planned should be culturally sensitive, locally relevant, acceptable and designed to address the specific needs of the communities. Additionally, there is a need for policies that support the financial aspects of cancer care, including expanding insurance coverage to providing transportation subsidies for patients who need to travel long distances for treatment. Thus, such policy-level reforms targeting the identified barriers at the community and the health system level could significantly accelerate meaningful change.

This study also highlights opportunities for future research. Firstly, there is a need for implementation research studies to document the impact of CHW-led interventions in facilitating cancer early detection and subsequent care, with a focus on sustainability and scalability of such interventions in the local context. There is a need for research that examines the broader social determinants of health affecting cancer care in rural India, examining the effects of poverty, inequity across social classes, urban-rural disparities, and gender norms on health-seeking behaviour. Complementary research into the cost-effectiveness of such policy interventions designed to address these determinants would also be of value, especially in the context of limited health.

Our study had several strengths. The CHWs were able to refer to several patient-provider experiences which adds richness to our study findings. Our commitment to rigorous qualitative methods adds rigour to the findings. Our study also examined the contribution of CHWs and the barriers they encounter across three states with varying levels of cancer care services. This approach provided valuable insights into the intricate and regionally diverse challenges of cancer care delivery in India. Despite its strengths, our study had a few limitations. The purposeful use of snowball sampling may have led to an overrepresentation of CHWs who were more vocal about the barriers they faced. However, to minimize this potential bias, we actively encouraged quieter participants to share their perspectives and ensured that diverse viewpoints were captured in the discussions. Notably, the majority of the CHWs surveyed were those who exceeded the standard expectation of their role, which was evident from the additional services they rendered. These findings may not be generalizable to activities performed by CHWs working in defined study settings. Additionally, our findings from TN may not be representative of the entire state, as it is influenced by the selection of a catchment area linked to a tertiary care centre, which naturally enhances the visibility and accessibility of cancer care.

This study highlights the vital role played by the CHWs play in enabling cancer early detection and subsequent care in rural India, while also highlighting their major personal, community level and health system level barriers. CHWs in rural India serve a more complicated and hard-to-reach population. By deepening our understanding of the complex factors that shape cancer care delivery in rural areas, future research can contribute to the development of more effective, equitable, and sustainable health systems. Our study has also laid down several policy-level implications that could reshape the CHW-led approach to cancer care delivery.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are included within the article.

The authors would like to thank the ACCI Consortium for their support and contributions. ACCI Consortium: Nandimandalam Venkata Vani, Rajaraman Swaminathan (Cancer Institute WIA, Tamil Nadu, India), Hardika Parekh, Rohit Rebello (Department of Medical Oncology, GBH Group of Hospitals, Udaipur, India). Arunah Chandran, Partha Basu, Sathishrajaa Palaniraja (International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France). Asiya Ansari Liji, Kunal Oswal, Moni Kuriakose, Ramadas Kunnambath, Rengaswamy Sankaranayanan, Priya Babu, Rita Isaac (Karkinos Healthcare, Mumbai, India). Richard Sullivan, Arnie Purushotham (King’s College London, London, UK). Brian Hutchinson, Ishu Kataria, Prince Bhandari, Rachel Nugent (RTI International). CS Pramesh (Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai, India).

This study was funded by MRC UK, as part of the call by the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD) (Funding number: MR/W023903/1). KT was funded by SNSF: grant number P500PM_210933. The funding body was not involved in the design of the study or in the preparation of this manuscript.

We obtained ethical approval from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IEC 2205) and all participating institutions. Regulatory approvals were sought from the Health Ministry Screening Committee (HMSC) of the Government of India (2022–17547) before commencing data collection. We informed all FGD participants about the study’s objectives and obtained a written informed consent. Participation in the FGDs was entirely voluntary, with no compensation or incentives provided to the participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer / World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer / World Health Organization.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Palaniraja, S., Taghavi, K., Kataria, I. et al. Barriers and contributions of rural community health workers in enabling cancer early detection and subsequent care in India: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 25, 1527 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22735-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22735-y