Ever since the public release of ChatGPT in the fall of 2022, classrooms everywhere from grade schools to universities have started to adapt to a new reality of AI-augmented education.

As with any new technology, the integration of AI into teaching practices has come with plenty of questions: Will this help or hurt learning outcomes? Are we grading students or an algorithm? And, perhaps most fundamentally: To allow, or not to allow AI in the classroom? That is the question keeping many teachers up at night.

For the instructors of Technology, Innovation, and Great Power Competition, a class created and taught by Stanford faculty and staff at the Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation (GKC), the answer to that question was obvious. Not only did they allow students to use AI in their coursework, they required it.

Taught by Steve Blank, Joe Felter, and Eric Volmar of the Gordian Knot Center, the class was a natural forum to discuss how emerging technologies will affect relations between the world’s most powerful countries.

Volmar, who returned to Stanford after serving in the U.S. Department of Defense, explains the logic behind requiring the use of AI:

“As we were designing this curriculum, we started from an acknowledgement that the world has changed. The AI models we see now are the worst they’re ever going to be. Everything is going to get better and become more and more integrated into our lives. So why not use every tool at our disposal to prepare students for that?”

For students used to restrictions or outright bans on using AI to complete coursework, being graded on using AI took some getting used to.

“This was the first class that I’ve had where using AI was mandatory,” said Jackson Painter, an MA student in Management Science and Engineering. “I’ve had classes where AI was allowed, but you had to cite or explain exactly how you used it. But being expected to use AI every week as part of the assignments was something new and pretty surprising.”

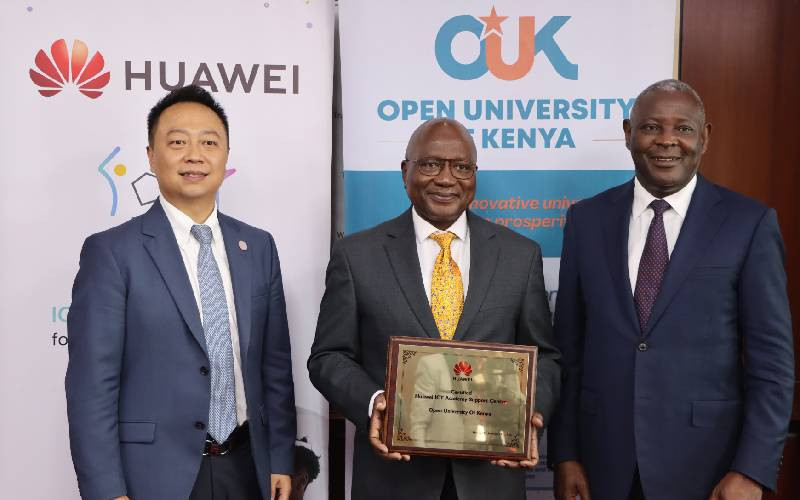

Eric Volmar teaching the new Stanford Gordian Knot Center course Entrepreneurship Inside Government. | Courtesy FSI

Assigned into teams of three or four, students were given an area of strategic competition to focus on for the duration of the class, such as computing power, semiconductors, AI/machine learning, autonomy, space, and cyber security. In addition to readings, each group was required to conduct interviews with key stakeholders, with the end goal of producing a memo outlining specific policy-relevant insights about their area of focus.

But the final project was only part of the grade. The instructors also evaluated each group based on how they had used AI to form their analysis, organize information, and generate insights.

“This is not about replacing true expertise in policymaking, but it’s changing the nature of how you do it,” Volmar emphasized.

For the students, finding a balance between familiar habits and using a novel technology took some practice.

“Before being in this class, I barely used ChatGPT. I was definitely someone who preferred writing in my own style,” said Helen Philips, an MA student in International Policy and course assistant for the class.

“This completely expanded my understanding of what AI is possible,” Philips continued. “It really opened up my mind to how beneficial AI can be for a broad spectrum of work products.”

After some initial coaching on how to develop effective prompts for the AI tools, students started iterating on their own. Using the models to summarize and synthesize large volumes of content was a first step. Then groups started getting creative. Some used AI to create maps of the many stakeholders involved in their project, then identify areas of overlap and connection between key players. Others used the tools to create simulated interviews with experts, then use the results to better prepare for actual interviews.

This is a new type of policy work. It’s not replacing expertise, but it’s changing the nature of how you access it. These tools increase the depth and breadth students can take in. It’s an extraordinary thing.”

Eric VolmarGKC Associate Director

For Jackson Painter, the class provided valuable practice combining more traditional techniques for developing policy with new technology.

“I really came to see how irreplaceable the interviewing process is and the value of talking to actual people,” said Jackson. “People know the little nuances that the AI misses. But then when you can combine those nuances with all the information the AI can synthesize, that’s where it has its greatest value. It’s about augmenting, not replacing, your work.”

That kind of synthesis is what the course instructors hope students take away from the class. The aim, explained Volmar, is that they will put it into practice as future leaders facing complex challenges that touch multiple sectors of government, security, and society.

“This is a new type of policy work,” he said. “It’s accelerated, and it increases the depth and breadth students can take in. They can move across many different areas and combine technical research with Senate and House Floor hearings. They can take something from Silicon Valley and combine it with something from Washington. It’s an extraordinary thing.”

For instructors Blank, Felter, and Volmar, classes like Technology, Innovation, and Great Power Competition – or sister classes like the highly popular Hacking for Defense, and the recently launched Entrepreneurship Inside Government – are an integral part of preparing students to navigate ever more complex technological and policy landscapes.

“We want America to continue to be a force for good in the world. And we’re going to need to be competitive across all these domains to do that. And to be competitive, we have to bring our A-game and empower creative thinking as much as possible. If we don’t take advantage of these technologies, we’re going to lose that advantage,” Felter stressed.

Applying real-time innovation to the challenges of national security and defense is the driving force behind the Gordian Knot Center. Founded in fall of 2021 by Joe Felter and Steve Blank with support from principal investigators Michael McFaul and Riita Katila, the center brings together Stanford’s cutting-edge resources, Silicon Valley’s dynamic innovation ecosystem, and a network of national security experts to prepare the next generation of leaders.

To achieve that, Blank leveraged his background as a successful entrepreneur and creator of the lean startup movement, a methodology for launching companies that emphasizes experimentation, customer feedback, and iterative design over more traditional methods based on complex planning, intuition, and “big design up front” development.

“When I first taught at Stanford in 2011, I observed that the teaching being done about how to write a business plan in capstone entrepreneurship classes didn’t match the hands-on chaos of an actual startup. There were no entrepreneurship classes that combined experiential learning with methodology. But the goal was to teach both theory and practice.”

What we’re seeing in these classes are students who may not have otherwise thought they have a place at the table of national security. That’s what we want, because the best future policymakers will understand how to leverage diverse skills and tools to meet challenges.”

Joe FelterGKC Center Director

That goal of combining theory and practice is a throughline that continues in today’s Gordian Knot Center. After the success of Blank’s entrepreneurship classes, he – alongside Pete Newell of BMNT and Joe Felter, a veteran, former senior Department of Defense official, and the current center director of the GKC – turned the principles of entrepreneurship and iteration toward government.

“We realized that university students had little connection or exposure to the problems that government was trying to solve, or the larger issues civil society was grappling with,” says Blank. “But with the right framework, students could learn directly about the nation's threats and security challenges, while innovators inside the government could see how students can rapidly iterate and deliver timely solutions to defense challenges.”

That thought led directly to the development of the Hacking for Defense class, now in its tenth year, and eventually to the organization of the Gordian Knot Center and its affiliate programs like the Stanford DEFCON Student Network. Based at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, the center today is a growing hub of students, veterans, alumni, industry experts, and government officials from a multiplicity of backgrounds and areas of expertise working across campus and across government to solve real problems and enact change.

Condoleezza Rice, director of the Hoover Institution, speaking in Hacking for Defense. | Courtesy FSI

In the classroom, the feedback cycle between real policy issues and iterative entrepreneurship remains central to the student experience. And it’s an approach that resonates with students.

“I love the fact that we’re addressing real issues in real time,” says Nuri Capanoglu, a master’s student in Management Science and Engineering who took Technology, Innovation, and Great Power Competition in fall 2024.

He continues, “Being able to use ChatGPT in a class like this was like having a fifth teammate we could bounce ideas off, double-check things, and assign to do complex literature reviews that wouldn’t have been possible on our own. It’s like we went from being a team of four to a team of fifty.”

Other students agree. Feedback on the class has praised the “fusion of practical hand-on learning and AI-enabled research” and deemed it a “must-take for anyone, regardless of background.”

Like many of his peers, Capanoglu is eager for more. “As I’ve been planning my future schedule, I’ve tried to find more classes like this,” he says.

For instructors like Felter and Volmar, they are equally ready to welcome more students into their courses.

“Policy is so complex now, and the stakes are so high,” acknowledged Felter. “But what we’re seeing in these classes is a passion for addressing real challenges from students who may not have otherwise thought they have a place at the table of national security or policy. That’s what we want. The best and brightest future policymakers are going to have diverse skill sets and understand how to leverage every possible tool and capability available to meet those challenges. So if you want to get involved and make a difference, come take a policy class.”

This story was originally published by the Freeman-Spogli Institute for International Studies.