Africa’s Digital Mirage: When ‘Local’ Tech Is Built on Foreign Foundations

Built on Rented Bricks: The Hidden Architecture

Everyone loves to talk about apps with African flavor, the clever UX, all the local languages, products that just fit. But look a little deeper and you’ll see what’s really powering most of these “local” startups. Underneath, it’s a patchwork of foreign services holding everything together. Hosting? That’s on foreign clouds. Payments? Handled by international rails. Distributing the app? That goes through global app stores. Even the basics — sending an SMS or verifying someone’s ID — rely on third-party APIs based outside Africa. Every time someone signs up, makes a payment, or just interacts with the app, a chunk of the action slips out of the continent as fees and control.

This isn’t nitpicking. Take an African merchant using what seems like a local e-commerce platform. She thinks she’s selling at home, but the tech behind it all bills in dollars. CDN caches? Probably not in-country. Credit card processing? Routed through foreign banks. Analytics? Tracked on servers oceans away. When someone downloads her app, they’re probably using Apple’s App Store or Google Play, both take a cut, set the rules, and scoop up billing data. Even a simple push notification has to pass through infrastructure run by American or European companies. And whenever a fintech app moves money, it usually settles through international banks or card networks that charge their own fees.

Developers face the same thing. Most of the tools, libraries, and platforms they use come from abroad, and the money flows that way too. Identity, email, SMS, the backend itself, they’re all foreign services. Local teams get really good at connecting all these pieces, but they’re not building new core systems from scratch. The things that look innovative are up front: slick UI, smart marketing, tailoring the flow to local habits. But the heavy lifting — servers, settlement engines, databases, the actual hardware — that’s all rented or outsourced.

This dependency isn’t just technical. It shapes how startups think and operate. They chase investor-friendly numbers and global reach, not true local ownership. It’s easier to stick with foreign vendors, you get to market faster. But that speed comes at a cost. The local economy keeps paying: recurring fees, lost control over data, and value that keeps flowing out, piling up elsewhere. In the end, only jobs and a bit of UX stay behind. The rest — the real value — leaves with every transaction.

Resellers, Not Builders: The Economic Consequences

When local startups become mostly resellers or just front-ends for foreign services, Africa misses out on building real technical muscle. There’s a world of difference between plugging into someone else’s payments API and actually running your own payments system. One lets you operate, sure, but you’re just paying monthly fees and using someone else’s tools. The other one? You build up skills, create jobs, own the intellectual property, and keep the profits at home. Right now, Africa does a lot of the first and not nearly enough of the second.

This comes with real economic costs. First, money leaks out—every month. Subscription fees, cloud bills, API charges, app store cuts—these all send cash overseas. A single transaction isn’t much, but when you add it up across an entire economy, it’s a massive drain, especially for digital markets that are just getting started. Second, there’s the problem of data loss and missed opportunities. When all the user data, usage stats, and payment histories live on foreign platforms, local companies can’t build valuable datasets or develop their own AI without asking for access. Third, there’s hardly any high-value creation happening upstream. The real money and expertise come from things like hardware, chip design, middleware, and big enterprise platforms. Jobs that pay well and create exportable IP grow out of those areas, but Africa barely touches them because most of the attention (and funding) goes to consumer apps.

The talent problem comes next. Engineers who dream of working on serious tech—real infrastructure, not just app front-ends—usually get better offers from foreign companies or remote gigs with Western firms. So, the most skilled people often leave, which just makes the problem worse. Local startups that stay small and depend on outside tools don’t invest in R&D, since vendor fees eat their profits and hardware or infrastructure projects look way too risky. It’s a cycle: lots of consumption, not much production.

And then, there’s the strategic risk. If there’s a geopolitical shakeup or some global crisis, relying on foreign tech turns into a big weakness. Prices can shoot up overnight, terms of service can change, or sanctions might hit, and suddenly local businesses can’t operate. One price hike on a core API, or a sudden app store policy shift, and entire markets can be thrown off course.

How to Move from Renters to Owners

Breaking out of the renter’s cycle takes real intent, money, and, honestly, a lot of patience. This isn’t about shutting out global tech — it’s about filling in the gaps at home so that value grows right where you live. Here’s what actually helps:

Start by owning your own infrastructure. Homegrown data centers, local cloud systems, and national ID frameworks keep money and control at home. When governments and regional groups throw in tax breaks, smart procurement, or team up with private players, local hosting suddenly looks a lot more appealing.

Latest Tech News

Decode Africa's Digital Transformation

From Startups to Fintech Hubs - We Cover It All.

Then, get serious about payment systems. Relying only on international cards means fees keep leaking out. Instead, countries can invest further in mobile money by establishing regional switches and local clearing houses. Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria have shown just how well this can work. If those systems then connect across borders, the benefits accumulate.

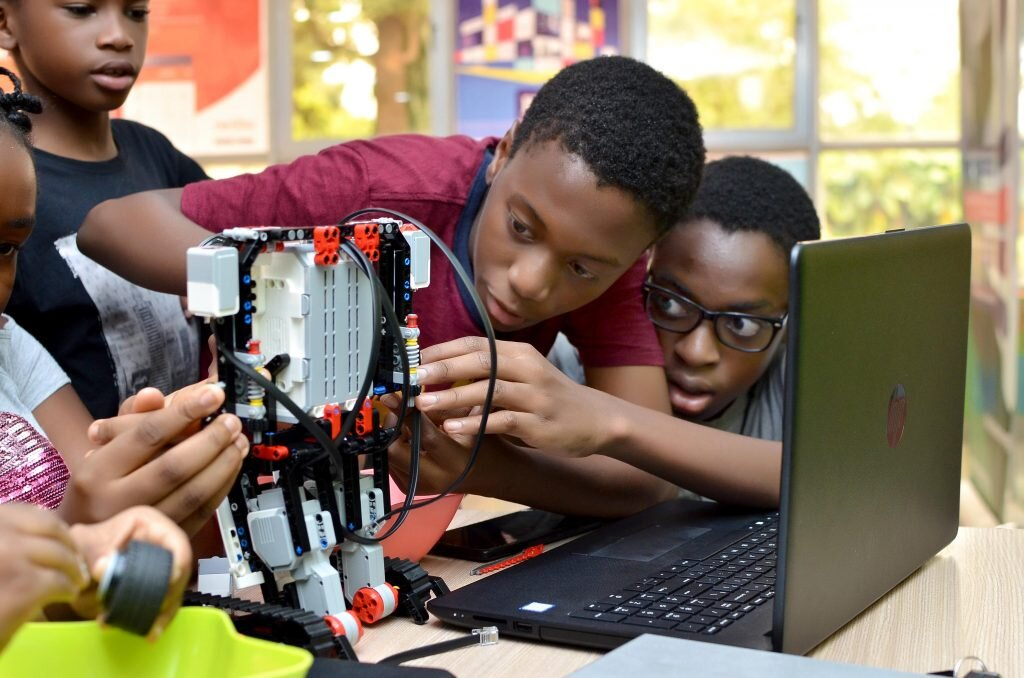

Next, invest in the tough stuff — core tech R&D. Chips, middleware, developer tools, open-source backbone projects. This takes patient funding from sovereign funds, development banks, even local venture capital. Hardware labs, fabless chip startups, and platform engineers need space to work. Universities and tech schools should go beyond teaching just front-end skills. We need more people building deep tech, systems engineering, distributed systems, embedded design.

Also, fix procurement. Governments and big companies can demand local data hosting and give preference to local providers, at least for general services. Predictable demand makes it worth building infrastructure from scratch.

Open-source matters too. African developers can team up on regional projects — payment platforms, ID checks, local language data sets — that break up vendor lock-in and build public tech everyone can use.

Most importantly, shine the light on what’s already working. Burkina Faso has grassroots solar manufacturing. Rwanda’s building up its own data centers and governance. Senegal’s betting on open-source education tools. These aren’t just stories — they’re proof that local solutions, built and run by locals, really work.

Bottom line: if you don’t make the basic layers yourself, you can’t really innovate. Maybe you’ll get good at integrating or adapting, but you’ll miss out on the bigger wins — owning the tech that brings in real money and power. For African tech to be truly African, the continent needs to stop building on rented land and start laying its own foundations: the code, servers, chips, and payment rails it actually owns. That’s how you stop copying foreign models and start creating real, homegrown value.

You may also like...

Bundesliga's New Nigerian Star Shines: Ogundu's Explosive Augsburg Debut!

Nigerian players experienced a weekend of mixed results in the German Bundesliga's 23rd match day. Uchenna Ogundu enjoye...

Capello Unleashes Juventus' Secret Weapon Against Osimhen in UCL Showdown!

Juventus faces an uphill battle against Galatasaray in the UEFA Champions League Round of 16 second leg, needing to over...

Berlinale Shocker: 'Yellow Letters' Takes Golden Bear, 'AnyMart' Director Debuts!

The Berlin Film Festival honored

Shocking Trend: Sudan's 'Lion Cubs' – Child Soldiers Going Viral on TikTok

A joint investigation reveals that child soldiers, dubbed 'lion cubs,' have become viral sensations on TikTok and other ...

Gregory Maqoma's 'Genesis': A Powerful Artistic Call for Healing in South Africa

Gregory Maqoma's new dance-opera, "Genesis: The Beginning and End of Time," has premiered in Cape Town, offering a capti...

Massive Rivian 2026.03 Update Boosts R1 Performance and Utility!

Rivian's latest software update, 2026.03, brings substantial enhancements to its R1S SUV and R1T pickup, broadening perf...

Bitcoin's Dire 29% Drop: VanEck Signals Seller Exhaustion Amid Market Carnage!

Bitcoin has suffered a sharp 29% price drop, but a VanEck report suggests seller exhaustion and a potential market botto...

Crypto Titans Shake-Up: Ripple & Deutsche Bank Partner, XRP Dips, CZ's UAE Bitcoin Mining Role Revealed!

Deutsche Bank is set to adopt Ripple's technology for faster, cheaper cross-border payments, marking a significant insti...