A pilot study investigating the effectiveness, appreciation, and feasibility of a cognitive stimulation program in dementia patients: online versus face-to-face

Dementia, a broad category of cognitive impairments affecting memory, thinking, and behavior, is a leading cause of disability among older adults worldwide (World Health Organization, 2021). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2019, approximately 55 million people were affected by dementia worldwide, with a projected increase to 78 million by 2030 (Li et al., 2024; GBD, 2022).

In Italy, as worldwide, dementia is one of the leading causes of disability among older adults, significantly impacting the quality of life of both patients and their caregivers. There are an estimated 1,126,961 cases of dementia in individuals aged 65 and older, as well as 23,730 cases of early-onset dementia in individuals aged 35–64 (ISS, 2024).

Managing dementia requires a multidisciplinary approach that includes early diagnosis, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, psychological support for the patient-caregiver dyad, and social care. In recent years, there has been increased focus on the importance of non-pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive stimulation, which has been shown to improve cognitive function and psychological wellbeing, as well as the overall quality of life of families (Pickett et al., 2018; Atay and Bahadır Yılmaz, 2024; Paggetti et al., 2024; Bertrand et al., 2023).

Many interventions have been implemented in recent decades, but cognitive stimulation (CS) has shown the strongest evidence for improving cognitive functions among various psychosocial approaches (McDermott et al., 2019; Desai et al., 2024). CS is a widely used non-pharmacological intervention aimed at improving or maintaining cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, language skills, and executive functions. It consists of thematic activities designed to exercise and train various cognitive areas through exercises, including more playful tasks like categorization, word association, discussion of current events, problem-solving, selective attention, and discussions (Woods et al., 2012; Spector et al., 2003). Sessions are led by an experienced facilitator who can adapt activities flexibly based on the patient’s interests, needs, cultural contexts, and cognitive/sensory abilities. The main goal of CS is to slow cognitive decline and improve the psychological wellbeing of participants. The therapeutic benefits of CS are well-documented, with studies highlighting its ability to improve cognitive skills such as memory and attention, as well as reduce the psychological symptoms of dementia (Capotosto et al., 2017; Gibbor et al., 2021a; Gibbor et al., 2021b; Saragih et al., 2022), in addition to having potential effects on brain physiology (Liu T. et al., 2021). Furthermore, CS is considered beneficial for caregivers as it reduces their stress and improves their satisfaction in providing care (Spector et al., 2003; Orrell et al., 2017; Lauritzen et al., 2023). Additionally, CS is the only non-pharmacological intervention recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to improve cognition, independence, and wellbeing in people with dementia (NIHCE, 2018; Cartabellotta et al., 2018).

Despite the evidence supporting its effectiveness (Lobbia et al., 2019; Pike et al., 2024), the World Alzheimer’s Report 2022 has recommended further research and the global implementation of CS, particularly in terms of user satisfaction and long-term effectiveness (Gauthier et al., 2022).

CS was initially developed as an in-person intervention. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need for remote therapeutic solutions, both to limit in-person healthcare access and to ensure continuity of care for patients with dementia (Liu K. Y. et al., 2021; Bethell et al., 2021; O’Connell et al., 2021; Santini et al., 2022). Consequently, the pandemic led to an increased use of technology for the delivery of remote healthcare services via videoconferencing platforms. In this context, the use of technology for delivering psychosocial interventions for people with dementia has become a rapidly expanding field (Cuffaro et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2023).

Reviews and meta-analyses examining the delivery of psychosocial interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers have demonstrated that virtual delivery was feasible and resulted in comparable outcomes to in-person delivery (Burton and O’Connell, 2018; Perkins et al., 2022; Fisher et al., 2024; Lai et al., 2020). Specifically, recent studies have explored the effectiveness of online interventions, with findings suggesting that video-conferenced CS can yield benefits similar to face-to-face delivery (Spector et al., 2024).

However, the inherent limitations of the “internet-based” modality must be acknowledged, including access to digital technology, the need for specific skills, ethical and security issues, as well as skepticism toward digital environments (Pywell et al., 2020; Yi et al., 2021). Despite these barriers, the benefits for individuals with reduced mobility, transportation difficulties, or those living in areas far from care centers are undeniable (Cuffaro et al., 2020; Adams et al., 2020; Angelopoulou et al., 2022).

In Italy, the development of telemedicine is relatively recent, with disparities among regions in the provision of related services (Maresca et al., 2020). In this context, considering its potential within the National Health Service, it remains crucial to assess the effectiveness and applicability of telemedicine interventions for patients with dementia, taking into account their specific needs and potential technological barriers. This pilot study aims to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a CS intervention for dementia patients, contributing to the development of more accessible and personalized therapeutic strategies.

Subjects were recruited at the Center for Cognitive Disorders and Dementia in Pisa. The inclusion criteria were as follows: they had to (1) meet the DSM-5 criteria for dementia, classified as Major Neurocognitive Disorder, as assessed by a trained clinician, following a comprehensive neurological and neuropsychological evaluation for the diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), (2) be classified as having mild or moderate dementia based on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (Morris, 1993), (3) do not have auditory or visual impairments, as assessed through clinical anamnesis, in order to engage in conversations and interpret visual materials and (4) able to communicate verbally in Italian. For those engaging in the videoconferencing mode, participants were required to have a desktop computer and be capable of conducting a video call using the selected platform for the sessions, if necessary, with the assistance of a caregiver only in case of technical difficulties or to verify a good connection, without interfering with the activities.

The study involved 19 dementia patients (Clinical Dementia Rating = 1 or 2), with 12 participating in in-person treatment and seven engaged remotely. Over the course of eight weekly 1 h sessions, patients participated in various cognitive activities, including memory, attention, and problem-solving exercises, guided by a clinical psychologist.

The “Internet-based” sessions utilized the televisita.sanita.toscana.it, a platform provided by the national healthcare system, while the “On-site condition” meetings were held at the Neurology Unit, Cognitive Disorders and Dementia Centre, Pisa University Hospital. All participants attended at least one introductory meeting; for those engaging in videoconference sessions, an additional “computer literacy” meeting was conducted to ensure proper use of the online platform. During this introductory meeting, it was verified that participants had the digital skills necessary for carrying out the activities (connection to the platform, turning on the microphone and camera, interaction, etc.). The sessions are synchronous and not recorded. During the videoconference sessions, in case of any difficulties with platform usage or connectivity, instant chat support, telephone contact, and an email address were provided as points of reference.

All participants provided written informed consent for participation, which included information on privacy and the handling of sensitive data. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee for Clinical Experimentation (Comitato Etico di Area Vasta Nord Ovest - CEAVNO) for the publication of aggregated, anonymized data collected from medical records without experimental procedures. The study adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined in the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

This protocol consists of eight weekly, 1 h individual sessions of CS for persons with dementia. Every session is led by a clinical psychologist, who was not involved in the assessment, with professional qualifications and expertise in neurodegenerative diseases. The meeting focuses on engaging the participant in cognitive activities designed to stimulate memory, attention, and problem-solving skills, as well as teaching compensatory strategies useful in daily life. The exercises are carefully calibrated to match the participant’s cognitive abilities and residual capacities, ensuring that they are appropriately challenging yet achievable. Each session begins with a brief and friendly greeting, designed to establish rapport and create a comfortable environment for the participant. Following the greeting, a short orientation exercise is conducted, where the participant is prompted to engage with details about the current day, date, time, and place. This helps stimulate attention and reinforces their temporal and spatial awareness. After the orientation, the session moves into focused exercises aimed at sharpening attention. These tasks may include simple visual or auditory attention tasks tailored to the participant’s cognitive level.

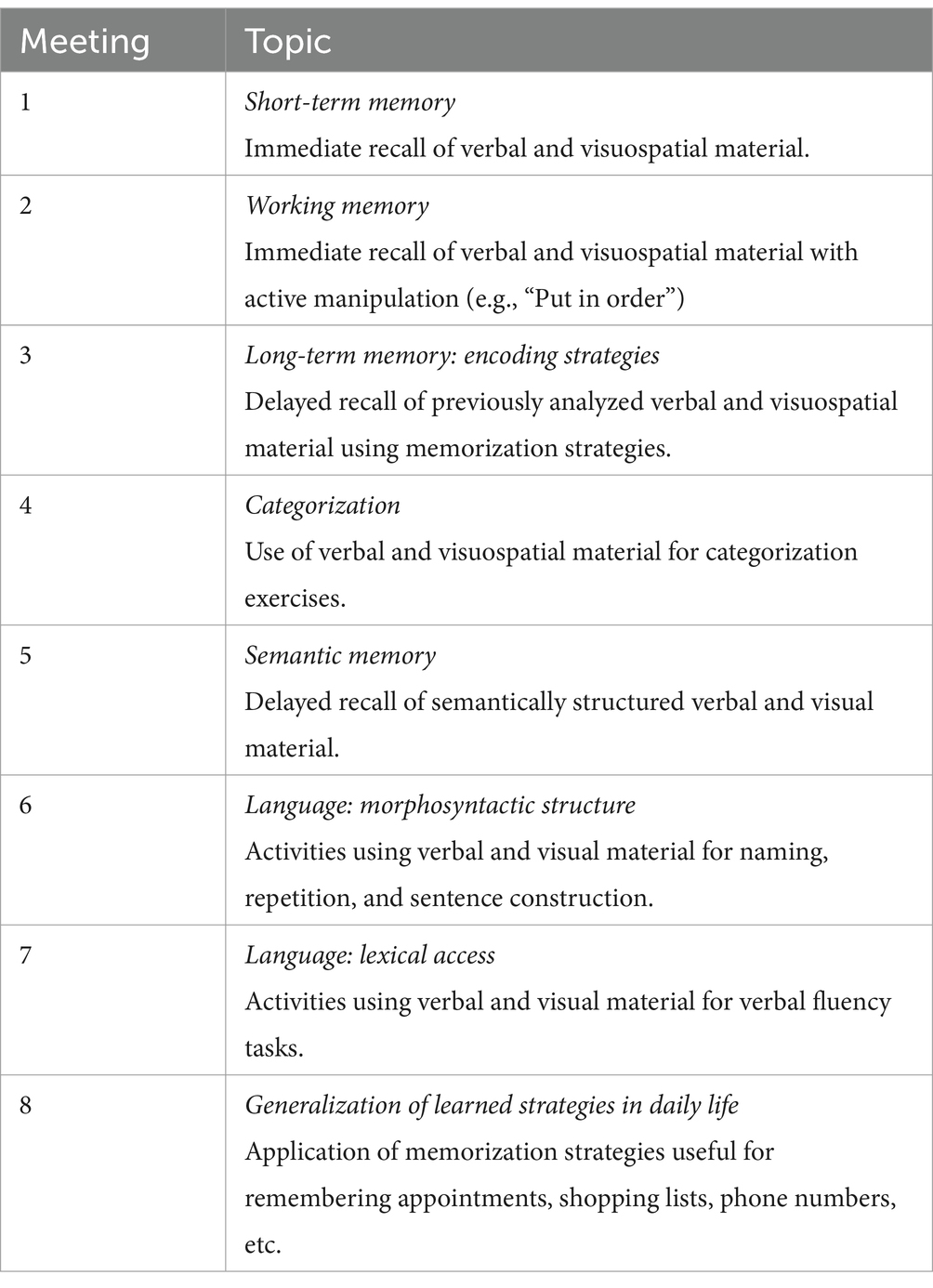

The main part of the session introduces the main theme of the meeting; the eight topics are summarized in Table 1. The exercises are adjusted in difficulty depending on the individual’s capabilities, with the goal of stimulating cognitive processes without causing frustration. Activities may involve recalling past events, solving simple problems, or engaging in discussions that require reasoning and attention. At the end of the main activity, the psychologist helps the participant generalize the cognitive skills practiced during the session, linking them to everyday activities or situations. This reflective step encourages the participant to recognize how these cognitive exercises can relate to their daily life and routines.

Each session concludes with a brief discussion of how the participant felt about the activities and any observations about their progress. The psychologist provides positive reinforcement and ends the session with a warm farewell, leaving the participant with a sense of accomplishment.

The protocol has been adapted to an online format, maintaining the characteristics of in-person execution. The sessions were conducted via videoconferencing platforms of the public health system. In this mode, both verbal and visual materials are used. Verbal instructions and discussions remain central to the session, while visual aids (e.g., images, documents, or interactive exercises) are shared through the screen-sharing function, ensuring that the participant can fully engage with the content.

Assessments were conducted using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975), Activities of Daily Living (ADL; Katz et al., 1963), and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL; Lawton and Brody, 1969) at the start (T0) and end (T1) of the intervention.

Visual-Analog Scale (VAS) scale is widely employed in subjectively assessing various variables (Voutilainen et al., 2016): specifically, a vertically oriented VAS ranging from 0 to 100 was utilized. Participants were asked to rate aspects proposed on this continuum, for example: “How useful do you feel participating in these sessions was for you from 0 (none) to 100 (very extensive)?” (Table 2).

Table 2. Crucial facets of the patients and caregiver experience linked to the cognitive stimulation sessions assessed using a visual-analog scale (VAS) at the end (T1) of the program.

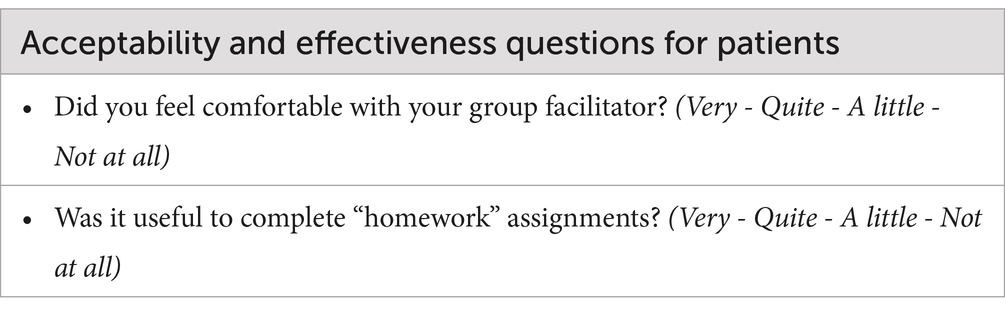

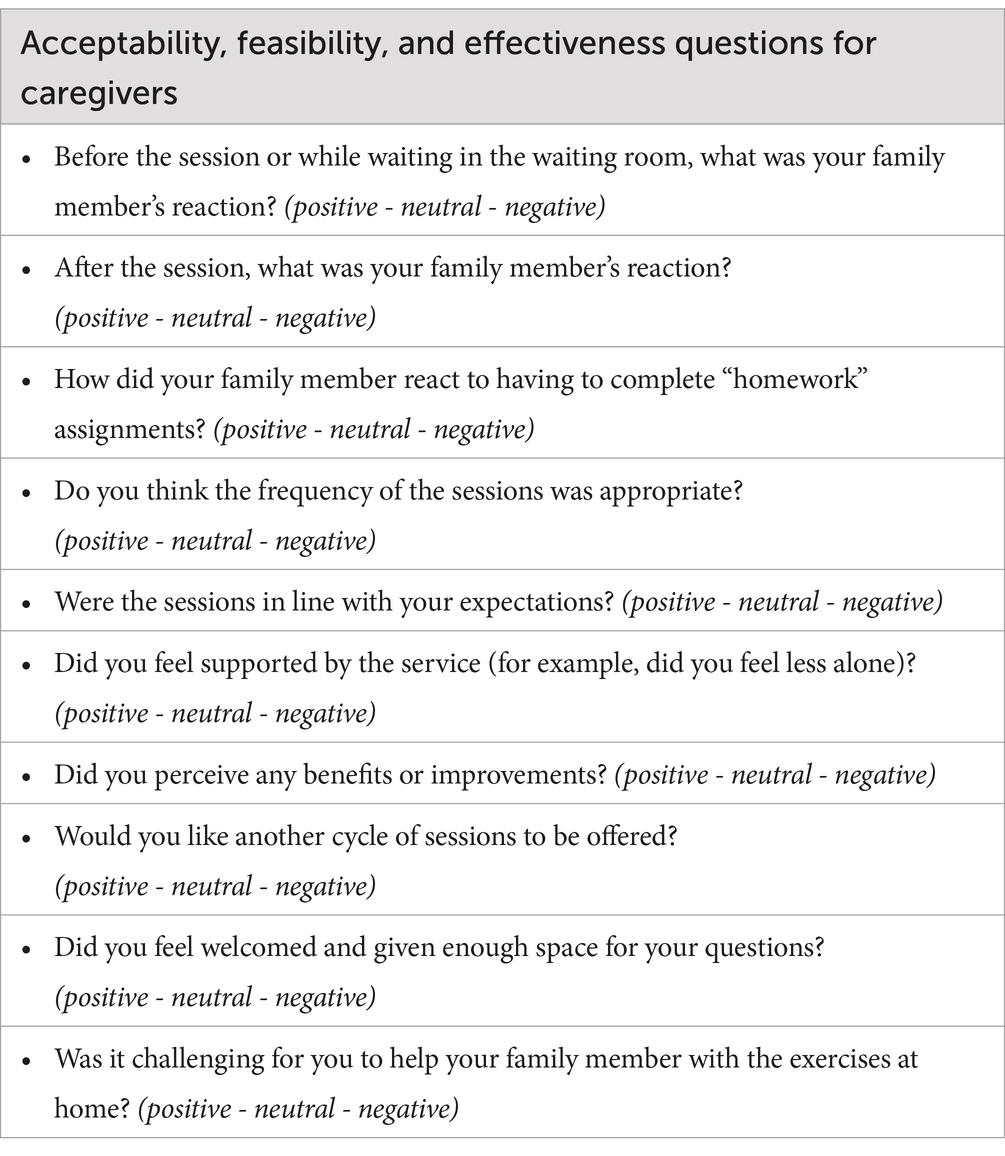

At the end of the program, both patients and caregivers were invited to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with specific statements by completing a 4-point or 3-point Likert scale (Tables 3, 4). In addition, the overall participation rate, dropout rate, and completion of outcome measures were taken into consideration.

Table 3. Research questions on the acceptability and effectiveness posed to patients with Likert scale at the end of the cognitive stimulation program.

Table 4. Research questions on the acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness posed to caregivers with Likert scale at the end of the cognitive stimulation program.

To describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population and aspects of experience related to the CS program, investigated using a Visual-Analog Scale, descriptive parameters were calculated, including the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD).

Differences between internet-based and on-site conditions groups for age, education, gender and type of dementia have been evaluated using for quantitative variables, unpaired t-tests or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test; for categorical variables, Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact method was applied. Shapiro–Wilk test was considered to test the normal distribution of quantitative variables.

For cognitive function (MMSE), daily living activities (ADL and IADL), and dementia severity (CDR) scores, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures (RM) was performed, considering both factor “group” (on-site condition or internet-based) and factor “time” (at beginning, T0, or at the end, T1), with post-hoc analysis Holm-Sidak method. Effect sizes (ES) were calculated using Cohen’s d statistic.

Statistical analyses were performed using statistical software package Sigma Stat 4.0; statistical significance was assumed for a p < 0.05.

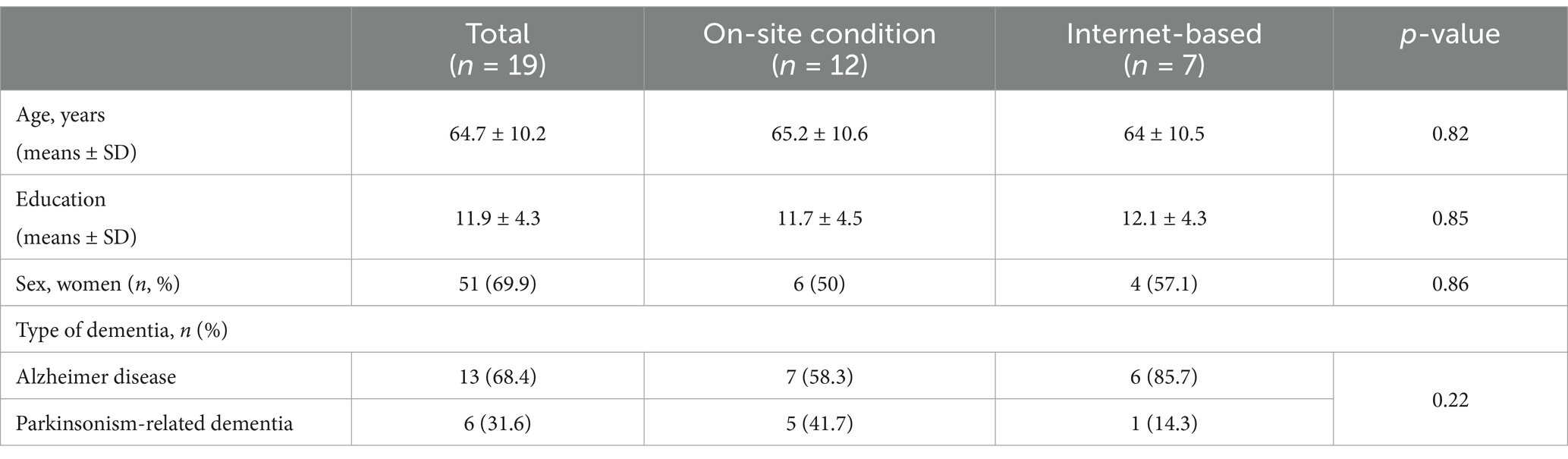

Of the 19 subjects, n = 12 followed the program in “on-site conditions,” while n = 7 were in “internet-based” group. The two groups exhibited similarity in age, education, gender and type of dementia (p > 0.05 for all p-value; Table 5); specifically, the mean age was around 65 years, with 12 years of education.

Table 5. Demographic characteristics of participants in on-site condition and internet-based [data are expressed as n, n (%), mean ± SD].

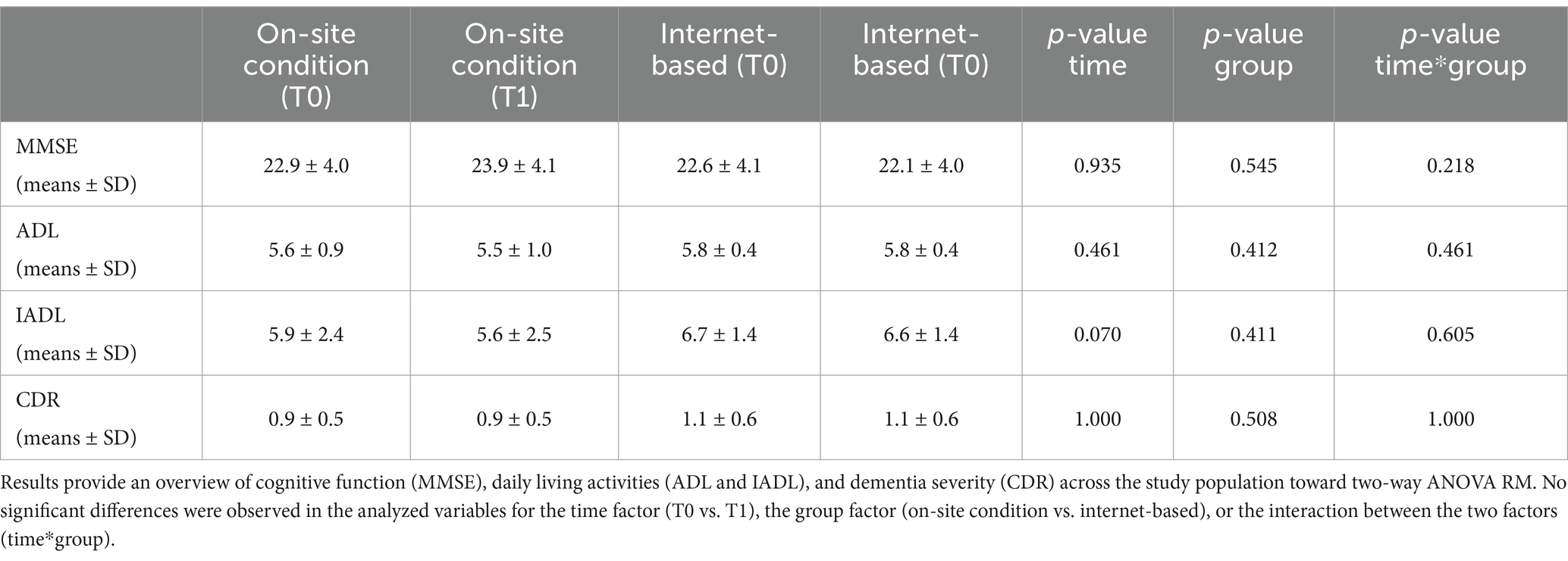

No differences were found at baseline in either global cognitive functioning measured by the MMSE, or in the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). These parameters remained stable throughout the duration of the intervention for both groups (Table 6). The severity of dementia and the degree of cognitive impairment in individuals also remained unchanged at the end of the CS program (Table 6), with a small effect size on dementia status (ES = 0.15 for MMSE; ES = 0.14 for CDR).

Table 6. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) and statistical analysis for MMSE, ADL, IADL, and CDR scores for two groups, on-site condition and internet-based, at beginning (T0) and at the end (T1) of cognitive stimulation program.

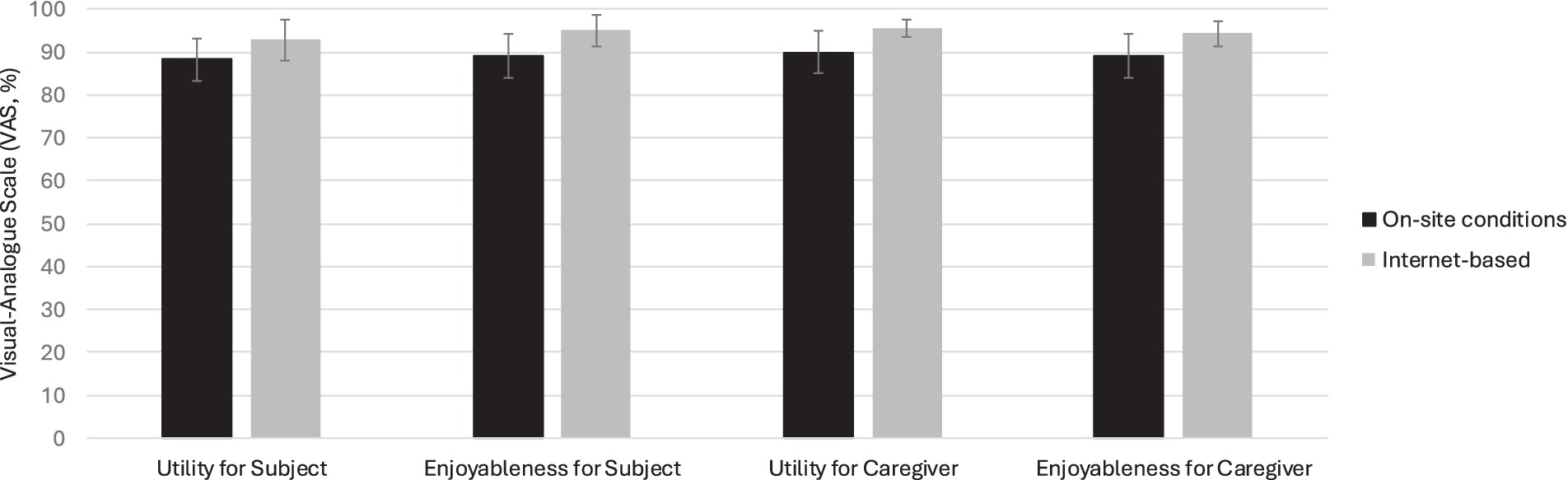

Both patients and caregivers reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention, providing positive feedback regarding the utility, enjoyment, and engagement in the sessions. At the end of the CS program, the subjects reported an overall utility of 90% and an enjoyment of 91.3%; caregivers’ assessments aligned with a mean score on the VAS scale of 92.1 and 91%, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two modalities (p > 0.05 for all p-values; Figure 1). Specifically, subjects found the relationship with the psychologist to be comfortable (94.7% of subjects responded “very” on the Likert scale), and they considered the assigned homework useful (52.6% responded “very” and 47.4% responded “quite” on the Likert scale) (Table 3). The average adherence rate was 92.86% for the “internet-based” group and 97.92% for the “on-site conditions” group. Specifically, the absences were due to personal and health-related reasons; only two patients were unable to attend a session due to connection issues. No dropouts occurred, and all outcome measures were completed by every participant.

Figure 1. Aspects of subjects and caregiver experience related to investigated using a visual-analog scale in internet based and on-site conditions at the and end (T1) of the program. Mann–Whitney rank sum test on-site condition and internet-based for “Utility for Subject and Caregiver,” “Enjoyableness for Subject and Caregiver” was performed with p > 0.05 for all p-values. Error bars = s.e.m.

Caregivers reported positive feelings regarding the family member’s reactions before (89.5% positive responses), after the sessions (100% positive responses), and in relation to the homework assignments (78.9% positive responses). Caregivers highlighted a high degree of appropriateness for the intervention regarding session frequency (89.5%) and alignment with their expectations (100%). The program was also found to be effective in providing support and welcoming the caregivers (100%), as well as fostering perceived benefits and improvements (89.5%). For half of the caregivers, it was challenging to assist their family member with the exercises at home (50%). Overall, all caregivers interviewed expressed great enthusiasm for the series of sessions and requested the implementation of a second cycle of meetings. Such feedback, recorded at the end of the CS program using the Likert scale (Table 4), was consistent in both the “on-site condition” and “internet-based” modalities.

The global prevalence of dementia, combined with its profound impact on patients and caregivers, has stimulated the search for interventions aimed at counteracting cognitive decline and improving quality of life. This study fits within this framework, documenting the effectiveness of CS in maintaining cognitive functions. Specifically, by incorporating both in-person and online modalities, this research evaluates the adaptability and feasibility of CS in different settings, assessing technological barriers in addition to the perceived benefit for caregivers.

Before the pandemic, few studies on the use of digital technologies in dementia care had already highlighted that, despite difficulties, offering online interventions to people with dementia was both possible and beneficial (Burton and O’Connell, 2018; World Health Organization, 2021; Dal Bello-Haas et al., 2014). Subsequently, with the onset of the pandemic, an increasing number of studies have corroborated these findings (Fisher et al., 2024; Gonzalez-Moreno et al., 2022; Spector et al., 2024; Santini et al., 2022).

The results indicate that CS, delivered both in-person and via videoconferencing, is feasible and well-received by both patients and caregivers. The absence of statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of cognitive functionality (MMSE scores) and daily activities (ADL and IADL scale scores) suggests that remote delivery is as effective as traditional in-person sessions. Although the MMSE may have limited sensitivity to subtle changes over time, particularly in critical age groups from 70 to 94 years (Aiello et al., 2022), its widespread use and reliability as a cognitive screening test make it a valuable tool. In our sample, with a mean age of approximately 65 years, this effect should be reduced, making the MMSE a valid tool in the context of the present pilot study. Both modalities achieved high participation and completion rates, reinforcing the adaptability of CS in different delivery formats.

Participants and caregivers reported high levels of satisfaction, with average scores above 90% in various domains, including perceived utility, enjoyment, and engagement. The therapeutic relationship with the psychologist was particularly appreciated, with over 94% of participants expressing comfort in this interaction. Caregivers also provided extremely positive feedback regarding the frequency of the program, alignment with expectations, and the support received. Despite some minor difficulties, such as assistance with homework tasks (reported by 50% of caregivers), the overall enthusiasm for the intervention highlights its potential acceptability, feasibility, and effectiveness for wider implementation.

The proposed cycle of sessions, in its brevity, includes activities designed to train various cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, and language, also within the context of daily use, promoting greater practical applicability. Additionally, it offers considerable flexibility, as it can easily be adapted to the specific needs of participants. The cycle can be repeated to consolidate the skills learned or to adjust the difficulty level. The exercises can be varied in their mode of delivery based on the participants’ remaining abilities. For example, for those with higher language skills, activities can emphasize verbal components such as storytelling or word games. Conversely, for individuals who prefer visuospatial tasks, exercises like image recognition or spatial orientation activities can be proposed. This personalization helps optimize engagement and the effectiveness of the intervention, making it accessible and meaningful for a wide range of participants.

The study results align with previous research highlighting the psychological and social benefits of CS (Cicerone et al., 2000; Clare et al., 2019), also in comparison to control groups (Gonzalez-Moreno et al., 2025). Moreover, the consistency of results across delivery modalities supports the idea that technological adaptation does not compromise the protocol’s effectiveness. This makes internet-based CS a service that complements face-to-face delivery, available at clinics, with the added advantage of increasing accessibility for those unable to attend in-person sessions due to various clinical, mobility, personal, transportation, or family management restrictions.

Low levels of digital literacy may represent a barrier for older adults (Fisher et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2020), as videoconference calls can be complex to set up and require high digital skills. As with previous studies, this one addressed this issue by providing preliminary support sessions for participants and families to resolve potential difficulties.

Caregivers spontaneously reported mood improvements following participation in CS sessions. Additionally, participants in the internet-based modality reported greater confidence and comfort with using digital technologies, such as videoconferencing calls.

Overall, this pilot study highlights the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of CS interventions delivered both in-person and online. The primary advantage lies in its adaptability, offering an inclusive approach to dementia care that addresses logistical challenges such as mobility and geographic access. The positive reception of the intervention by patients and caregivers, along with comparable results across modalities, underscores its potential for broader application in clinical practice.

Feedback indicated that remote participation was well-received, with no significant technological issues or barriers to interaction reported. Furthermore, participants from both groups demonstrated similar levels of participation and interaction, supporting the feasibility of remote treatment as a valid alternative to in-person sessions. These results suggest that the intervention can be successfully delivered remotely without compromising patient engagement or care outcomes.

However, the study has some limitations. The small sample size limits the generalizability of the results, and the short duration of the intervention does not allow for conclusions on its long-term effectiveness. Additionally, although caregivers provided positive feedback, their role in supporting home exercises requires further exploration to address potential difficulties and improve their involvement in relation to caregiver burden outcomes. Additional objective measurements to increase sensitivity in detecting changes over time and to assess further outcomes related to the neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients would be useful to confirm the positive perception reported by their family members. While acknowledging that the lack of a control group and the absence of randomization represent methodological limitations, it is important to emphasize the focus on exploring feasibility and gathering preliminary data for future, broader, and more rigorous research. Moreover, in a “real world” context, the uncontrolled nature of the intervention allows for the observation of individual dynamics in situations that are closer to everyday clinical practice.

Future research should focus on expanding the intervention to include a larger and more diverse sample and extending the program duration to assess sustained benefits over time. Investigating digital literacy and accessibility could inform strategies to reduce barriers to remote delivery. Additionally, exploring the integration of personalized caregiver support within the CS framework could enhance the overall impact of the intervention.

In conclusion, this study provides valuable evidence supporting the usefulness of CS in dementia care and highlights the potential of remote modalities to expand access to effective, person-centered interventions. Further research and refinements are essential to optimize delivery and maximize benefits for patients and caregivers.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Comitato Etico Regione Toscana—Area Vasta Nord Ovest (CEAVNO). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

SC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. VG: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VN: Writing – review & editing. EP: Writing – review & editing. DF: Writing – review & editing. RC: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. GT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adams, J. L., Myers, T. L., Waddell, E. M., Spear, K. L., and Schneider, R. B. (2020). Telemedicine: a valuable tool in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 9, 72–81. doi: 10.1007/s13670-020-00311-z

Aiello, E. N., Pasotti, F., Appollonio, I., and Bolognini, N. (2022). Trajectories of MMSE and MoCA scores across the healthy adult lifespan in the Italian population. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 34, 2417–2420. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02174-0

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Angelopoulou, E., Papachristou, N., Bougea, A., Stanitsa, E., Kontaxopoulou, D., Fragkiadaki, S., et al. (2022). How telemedicine can improve the quality of Care for Patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias? A narrative review. Medicina 58:1705. doi: 10.3390/medicina58121705

Atay, E., and Bahadır Yılmaz, E. (2024). The effect of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) on apathy, loneliness, anxiety and activities of daily living in older people with Alzheimer’s disease: randomized control study. Aging Ment. Health 12, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2024.2437060

Bertrand, E., Marinho, V., Naylor, R., Bomilcar, I., Laks, J., Spector, A., et al. (2023). Metacognitive improvements following cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia: evidence from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Gerontol. 46, 267–276. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2022.2155283

Bethell, J., O’Rourke, H. M., Eagleson, H., Gaetano, D., Hykaway, W., and McAiney, C. (2021). Social connection is essential in long-term care homes: considerations during COVID-19 and beyond. Canadian Geriatrics J. 24, 151–153. doi: 10.5770/cgj.24.488

Burton, R. L., and O’Connell, M. E. (2018). Telehealth rehabilitation for cognitive impairment: randomized controlled feasibility trial. JMIR Res. Protocols. 7:e43. doi: 10.2196/resprot.9420

Capotosto, E., Belacchi, C., Gardini, S., Faggian, S., Piras, F., Mantoan, V., et al. (2017). Cognitive stimulation therapy in the Italian context: its efficacy in cognitive and non-cognitive measures in older adults with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 32, 331–340. doi: 10.1002/gps.4521

Cartabellotta, A., Eleopra, R., Quintana, S., Pingani, L., Ferrarese, C., Starace, F., et al. (2018). Linee guida per la diagnosi, il trattamento e il supporto dei pazienti affetti da demenza. Evidence 10:e1000190. doi: 10.4470/E1000190

Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Kalmar, K., Langenbahn, D. M., Malec, J. F., Bergquist, T. F., et al. (2000). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: recommendations for clinical practice. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 81, 1596–1615. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.19240

Clare, L., Kudlicka, A., Oyebode, J. R., Jones, R. W., Bayer, A., Leroi, I., et al. (2019). Goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation for early-stage Alzheimer’s and related dementias: the GREAT RCT. Health Technol Assess. 23, 1–242. doi: 10.3310/hta23100

Cuffaro, L., Di Lorenzo, F., Bonavita, S., Tedeschi, G., Leocani, L., and Lavorgna, L. (2020). Dementia care and COVID-19 pandemic: a necessary digital revolution. Neurol. Sci. 41, 1977–1979. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04512-4

Dal Bello-Haas, V., O’Connell, M. E., Morgan, D. G., and Crossley, M. (2014). Lessons learned: feasibility and acceptability of a telehealth-delivered exercise intervention for rural-dwelling individuals with dementia and their caregivers. Rural Remote Health 14:2715. doi: 10.22605/RRH2715

Desai, R., Leung, W. G., Fearn, C., John, A., Stott, J., and Spector, A. (2024). Effectiveness of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for mild to moderate dementia: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of randomised control trials using the original CST protocol. Ageing Res. Rev. 97:102312. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2024.102312

Fisher, E., Proctor, D., Perkins, L., Felstead, C., Stott, J., and Spector, A. (2023). Is virtual cognitive stimulation therapy the future for people with dementia? An audit of UK NHS memory clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 8, 360–367. doi: 10.1007/s41347-023-00306-5

Fisher, E., Venkatesan, S., Benevides, P., Bertrand, E., Brum, P. S., El Baou, C., et al. (2024). Online cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia in Brazil and India: acceptability, feasibility, and lessons for implementation. JMIR Aging. 7:e55557. doi: 10.2196/55557

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., and McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Gauthier, S., Webster, C., Servaes, S., Morais, J. A., and Rosa-Neto, P. (2022). World Alzheimer report 2022: Life after diagnosis: Navigating treatment, care and support. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

GBD (2022). Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study (GBD) 2019. Lancet Public Health 7, e105–e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8

Gibbor, L., Forde, L., Yates, L., Orfanos, S., Komodromos, C., Page, H., et al. (2021b). A feasibility randomised control trial of individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: impact on cognition, quality of life and positive psychology. Aging Ment. Health 25, 999–1007. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1747048

Gibbor, L., Yates, L., Volkmer, A., and Spector, A. (2021a). Cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for dementia: a systematic review of qualitative research. Aging Ment. Health 25, 980–990. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1746741

Gonzalez-Moreno, J., Satorres, E., Soria-Urios, G., and Meléndez, J. C. (2022). Cognitive stimulation program presented through new Technologies in a Group of people with moderate cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 88, 513–519. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220245

Gonzalez-Moreno, J., Soria-Urios, G., Satorres, E., and Meléndez, J. C. (2025). Comparing traditional and technology-based methods for executive function and attention training in moderate Alzheimer's dementia. Psicothema 37, 42–49. doi: 10.70478/psicothema.2025.37.05

ISS (2024). Progetto fondo per l’Alzheimer e le demenze - le attività dell’osservatorio demenze dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanità (Anni 2021–2023) Report Nazionale. Rome: Istituto Superiore Di Sanità.

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A., and Jaffe, M. W. (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185, 914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

Lai, F. H., Yan, E. W., Yu, K. K., Tsui, W. S., Chan, D. T., and Yee, B. K. (2020). The protective impact of telemedicine on persons with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 28, 1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.019

Lauritzen, J., Nielsen, L. M., Kvande, M. E., Brammer Damsgaard, J., and Gregersen, R. (2023). Carers’ experience of everyday life impacted by people with dementia who attended a cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) group intervention: a qualitative systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 27, 343–349. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2022.2046699

Lawton, M. P., and Brody, E. M. (1969). Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist 9, 179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179

Li, Z., Yang, N., He, L., Wang, J., Yang, Y., Ping, F., et al. (2024). Global burden of dementia death from 1990 to 2019, with projections to 2050: an analysis of 2019 global burden of disease study. J. Prev Alzheimers Dis. 11, 1013–1021. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2024.21

Liu, K. Y., Howard, R., Banerjee, S., Comas-Herrera, A., Goddard, J., Knapp, M., et al. (2021). Dementia wellbeing and COVID-19: review and expert consensus on current research and knowledge gaps. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36, 1597–1639. doi: 10.1002/gps.5567

Liu, T., Spector, A., Mograbi, D. C., Cheung, G., and Wong, G. H. Y. (2021). Changes in default mode network connectivity in resting-state fMRI in people with mild dementia receiving cognitive stimulation therapy. Brain Sci. 11:1137. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11091137

Lobbia, A., Carbone, E., Faggian, S., Gardini, S., Piras, F., Spector, A., et al. (2019). The efficacy of cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) for people with mild-to-moderate dementia: a review. Eur. Psychol. 24, 257–277. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000342

Maresca, G., Maggio, M. G., De Luca, R., Manuli, A., Tonin, P., Pignolo, L., et al. (2020). Tele-neuro-rehabilitation in Italy: state of the art and future perspectives. Front. Neurol. 11:563375. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.563375

McDermott, O., Charlesworth, G., Hogervorst, E., Stoner, C., Moniz-Cook, E., Spector, A., et al. (2019). Psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Aging Ment. Health 23, 393–403. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1423031

NIHCE (2018). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. Guideline. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

O’Connell, M. E., Vellani, S., Robertson, S., O’Rourke, H. M., and McGilton, K. S. (2021). Going from zero to 100 in remote dementia research: a practical guide. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e24098. doi: 10.2196/24098

Orrell, M., Yates, L., Leung, P., Kang, S., Hoare, Z., Whitaker, C., et al. (2017). The impact of individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) on cognition, quality of life, caregiver health, and family relationships in dementia: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. 14:e1002269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002269

Paggetti, A., Druda, Y., Sciancalepore, F., Della Gatta, F., Ancidoni, A., Locuratolo, N., et al. (2024). The efficacy of cognitive stimulation, cognitive training, and cognitive rehabilitation for people living with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geroscience. 47, 409–444. doi: 10.1007/s11357-024-01400-z

Perkins, L., Fisher, E., Felstead, C., Rooney, C., Wong, G. H. Y., Dai, R., et al. (2022). Delivering cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) virtually: developing and field-testing a new framework. Clin. Interv. Aging 17, 97–116. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S348906

Pickett, J., Bird, C., Ballard, C., Banerjee, S., Brayne, C., Cowan, K., et al. (2018). A roadmap to advance dementia research in prevention, diagnosis, intervention, and care by 2025. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 33, 900–906. doi: 10.1002/gps.4868

Pike, K. E., Li, L., Naismith, S. L., Bahar-Fuchs, A., Lee, A., Mehrani, I., et al. (2024). Implementation of cognitive (neuropsychological) interventions for older adults in clinical or community settings: a scoping review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 6, 1–29. doi: 10.1007/s11065-024-09650-6

Pywell, J., Vijaykumar, S., Dodd, A., and Coventry, L. (2020). Barriers to older adults’ uptake of mobile-based mental health interventions. Digital Health. 6:205. doi: 10.1177/2055207620905422

Santini, S., Rampioni, M., Stara, V., Di Rosa, M., Paciaroni, L., Paolini, S., et al. (2022). Cognitive digital intervention for older patients with Parkinson’s disease during COVID-19: a mixed-method pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:14844. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214844

Saragih, I. D., Tonapa, S. I., Saragih, I. S., and Lee, B. O. (2022). Effects of cognitive stimulation therapy for people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 128:104181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104181

Spector, A., Abdul Wahab, N. D., Stott, J., Fisher, E., Hui, E. K., Perkins, L., et al. (2024). Virtual group cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: mixed-methods feasibility randomized controlled trial. The Gerontologist 64:gnae063. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnae063

Spector, A., Orrell, M., Ree, J., and Woods, B. (2003). Cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 58, P45–P53. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.1.P45

Tan, L. F., Ho Wen Teng, V., Seetharaman, S. K., and Yip, A. W. (2020). Facilitating telehealth for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: strategies from a Singapore geriatric center. Geriatr Gerontol Int 20, 993–995. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14017

Voutilainen, A., Pitkäaho, T., Kvist, T., and Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. (2016). How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 946–957. doi: 10.1111/jan.12875

Woods, B., Rai, H. K., Elliott, E., Aguirre, E., Orrell, M., and Spector, A. (2012). Cognitive stimulation to improve cognitive functioning in people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2:CD005562. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005562.pub2

World Health Organization (2021). Global status report on the public health response to dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization.