A Life course approach to investigate breast cancer and migration in the greater Paris area: the SENOVIE study protocol

A Life course approach to investigate breast cancer and migration in the greater Paris area: the SENOVIE study protocol

Breast cancer is a global public health challenge. It is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death in women. Several inequalities remain among women facing this disease, depending on their country of birth and their sociodemographic characteristics. The SENOVIE study (Therapeutic mobility and breast cancer) aims to understand the life trajectories of women born in France and in sub-Saharan Africa treated for breast cancer in four hospitals in the greater Paris area.

The SENOVIE study is a mixed methods study, combining a quantitative and a qualitative approach. A quantitative retrospective life-event survey is conducted in four hospital centres in the greater Paris area, France, to (1) understand how breast cancer (diagnosis, treatment and possibly reconstruction) impacts the life trajectories of women in many spheres (migration, family life, professional life, financial situation, etc); (2) study the access to healthcare by women living with breast cancer and their determinants; and (3) examine how gender relations may shape breast cancer experience. Women born in France and women born in sub-Saharan Africa are recruited: 1000 women, including 500 per group. In the standardised, face-to-face questionnaire, each dimension of interest is collected year by year from birth until the time of the survey. Clinical and laboratory information is documented with a short medical questionnaire filled out by the medical teams. The qualitative survey is conducted specifically with women born in sub-Saharan Africa who came to France for treatment to better understand their trajectories and the specific obstacles they faced. To analyse the quantitative data collected, descriptive analyses will be used to visualise trajectories (sequence analysis), along with longitudinal analysis methods (survival models and duration models).

The study is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The French Data Protection Authority (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, declaration number 2231238) and the Committee for Persons’ Protection East I (Comité de Protection des Personnes Est I, national number 2023-A01311-44) approved it. We will disseminate the findings through scientific publications, policy briefs, conferences and workshops.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

According to the Global Cancer Observatory, around 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022, representing 11.6% of all cancer cases and, it is the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Among women, breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide.1

Mortality rates have been falling since the early 1990s in high-income countries, reflecting the progress made through numerous therapeutic advances and improvements in early detection through screening and increased awareness.2–4 However, in low-income and middle-income countries, breast cancer incidence and mortality are rising rapidly.5–8 The rapid increase in breast cancer cases in low-income and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, could be partly explained by demographic changes (increasing age at first childbearing, ageing), changes in lifestyles and comorbidities (obesity, sedentary lifestyle, etc), decrease in breastfeeding, alcohol consumption.5 9 10 The rising mortality rate could be due to the limited access to screening, particularly mammography, late-stage disease presentation and a health system poorly equipped for the management of breast cancer.8 11 12 These differences between regions raise the question of the differences that could be observed within a country, depending on women’s country of birth. However, while studies considering place of birth have been carried out in some Western countries, with mixed results,13–15 to our knowledge this has rarely been done in France.

In France, breast cancer accounts for 33% of women’s cancers, and its incidence has been rising since the 1990s to reach a global standardised incidence rate of 99.2 per 1 00 000 women in 2023.16 In 2017, its prevalence was estimated at 913 089 people in France.17

As pointed out by the Lancet Breast Cancer Commission, equity is a major issue in breast cancer.18 A systematic review carried out at the European level shows how socioeconomic inequalities shape breast cancer patterns: the incidence of breast cancer is higher in the most educated women (due to reproductive factors such as a higher age at first child, breastfeeding and also other factors such as alcohol consumption, family history, hormonal treatments), whereas the case fatality rate is higher for disadvantaged women.19 The situation seems identical in France, as the 5-year net survival rate is lower among people living in disadvantaged areas compared with women living in advantaged areas.20 The available studies in France point to discrepancies in the use of screening according to women’s age, level of education and economic and geographical situation.21–26 Concerning the post-cancer period, the results of the VICAN5 study (Living conditions five years after a cancer diagnosis) — conducted in metropolitan France in 2015 — also showed the importance of social inequalities on the repercussions of breast cancer on women’s lives: women from a disadvantaged background experience more financial consequences of breast cancer, and they also have a lower quality of life 5 years after their diagnosis.27 A recent study based on cohort data even showed increased inequalities in quality of life over time.28 Hence, breast cancer cannot be tackled without taking health inequalities into account.

To date, and to our knowledge, there are no data in France documenting breast cancer experience according to women’s country of birth. However, all the available data suggest that immigrant women could face specific obstacles in the experience of breast cancer. First, young age is the main characteristic of breast cancer in sub-Saharan African women.29 Second, triple-negative cases of breast cancer represent more than one-third of the breast cancers in sub-Saharan Africa.30–32 In contrast, they represent less than 15% in France.33 34 Third, the age at which cancer occurs is different: 70% of women diagnosed with breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa are under 50 years of age35 compared with a median of 64 years in women born in France.17 The characteristics of the cancer could be one element that results in more critical consequences in women’ lives. However, other factors, documented in other health areas, could also play a role: the role of poverty and precarity, difficulties in accessing health insurance and healthcare, language problems, the difficult process of settling in, which takes several years, the lack of stable financial resources, more frequent situations of isolation.36 37

The few studies on breast cancer screening that consider women’s country of birth suggest that immigrant women are indeed more likely to not have breast cancer screening (9.8% vs 7.6% among natives) and more likely to have this screening late (30.6% vs 18%).38 We have not found published studies documenting the incidence and mortality of breast cancer among immigrants in France, particularly women from sub-Saharan Africa. The few studies that do exist, which are mainly qualitative, highlight the difficulties encountered by immigrant women in accessing healthcare.39–41 In the French context, where there is still a reluctance to collect and study data according to origin,42 data are lacking to better understand immigrant women’s life trajectories with breast cancer.

In 1982, Bury introduced the notion of biographical disruption in analysing the experience of chronic diseases based on the example of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.43 He argued that “illness, and especially chronic illness, is precisely that kind of experience where the structures of everyday life and the forms of knowledge which underpin them are disrupted”. Thus, the disease’s arrival marks a rupture, a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ in the life trajectory of individuals. To understand how breast cancer affects different dimensions of women’s lives (occupation, residential, family, etc) across times, a life course approach seems necessary.

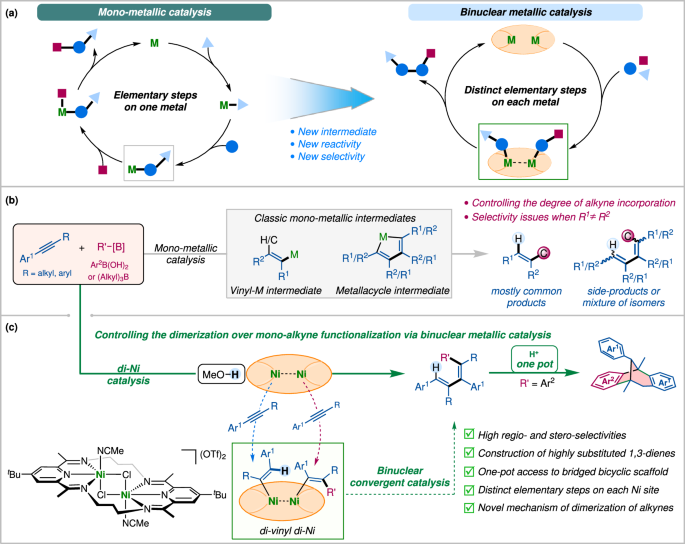

Two dimensions, in particular, could be usefully investigated through a life course approach that are seldom present in other longitudinal (cohort) data. The first one is to study how the experience of illness also calls for a reconstruction of identity that advocates continuity and involves gender issues.44 Research carried out in France has shown the strong presence of gender norms and stereotypes in the cancer care pathways, and the strongly gendered dimension of the body being treated. Meidani and Alessandrin note that in relationships with the body, to relatives, and to sexual and aesthetic issues, gender is always present.44 The authors thus suggest that gender is present at all stages of the fight against the disease, particularly in the various stages of identity reconstruction. A recent study, conducted as part of the international SENOVIE project (figure 1), showed that among women living in Mali, undergoing a mastectomy prevented them from performing typically female functions in society (such as cooking or sexuality), thus challenging their female identity.45

Figure 1

The international SENOVIE project (Therapeutic mobility and breast cancer. The international SENOVIE project aims to study the link between breast cancer and therapeutic mobility. Its general aim is to understand the reasons for and consequences of the therapeutic mobility of women affected by breast cancer. It is being carried out in France, Mali, Benin and Cambodia, using a mixed methodology and a multidisciplinary, cross-sectoral approach. A detailed description can be found on the project website (https://www.senovie.org/).

Another dimension which is crucial in understanding immigrant women’s experience of cancer is to be able to understand how the diagnosis appears in relation to a context of migration. In this regard, two different situations can be found: the first one is that women are diagnosed while they have been living in France for some time. Depending on the timing of diagnosis regarding migration (are they well settled? Do they already have a personal home or a job?), the consequences of the diagnosis could be different. Another situation is the one of women who came to France after being diagnosed with breast cancer in their country of origin for treatment. Their coming to France can be related to what is called therapeutic mobility.46–48 Concerning therapeutic mobilities, previous qualitative research showed that women who had undertaken therapeutic mobility had very heterogeneous profiles: some belonged to a high socioprofessional category, but others had low social and economic capital and had complex backgrounds. For these women, therapeutic mobility was seen as a unique chance of survival. In addition, access to care for these women is in precarious conditions related to housing, administrative situation and emotional life.41 Thus, the consequences of the diagnosis could be even more dramatic, and the trajectories in France even more difficult for these women who left their countries to find healthcare.

To contribute to the understanding of social health inequalities in breast cancer in France, the aim of our study is to understand the life trajectories of women born in France and in sub-Saharan Africa treated for breast cancer.

The SENOVIE France study is taking place in the greater Paris area, in the four partner structures of the study, namely: the Saint Louis Hospital in Paris, the Delafontaine Hospital Center in Saint-Denis, the Robert Ballanger Intercommunal Hospital Center in Aulnay-sous-Bois and the Avicenne Hospital in Bobigny. The project was developed in collaboration with the heads of the oncology and senology departments of these hospitals in order to recruit, during consultations, women treated for breast cancer in these hospitals. Given that the study aims to recruit women born in France and in sub-Saharan Africa, the study was designed taking into account the diversity of patients consulting in the hospitals as well as their locations, in particular Saint-Denis, Aulnay-sous-Bois and Bobigny, which are cities in the Seine Saint-Denis department with a more significant share of immigrant population than Paris. In 2020–2021, immigrants represented 32% of the population of Seine-Saint-Denis compared with 10% of the population in France excluding Mayotte.49

Study design and objectives

The SENOVIE France quantitative study is a retrospective, life-event survey. This methodology has the great advantage of collecting longitudinal data while avoiding attrition, which is very frequent in prospective cohorts among disadvantaged populations: women are surveyed one time and are asked retrospectively about the sequence of events that have occurred in their lives, at different points in time (months, years). This methodology enables researchers to capture the dynamics of events and their interactions.50 A similar methodology has been successfully used in the field of HIV and hepatitis B among immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa living in the greater Paris area by several members of the project.51–53

As part of the SENOVIE France project, this methodology is used with the aim of (1) understanding how breast cancer (diagnosis, treatment and reconstruction) impacts the life trajectories of women (migration, family life, professional life, financial situation, etc); (2) studying the access to healthcare (including self-reconstruction) of French-born women and immigrant women from sub-Saharan Africa living with breast cancer and their determinants; and (3) examining how gender relations may shape breast cancer management. These general objectives are linked to a number of specific objectives presented in table 1. A mixed methodology combining a quantitative and a qualitative approach is adopted to meet these different objectives.

Table 1

General and specific objectives of the SENOVIE France study (Therapeutic mobility and breast cancer).

Study population

The SENOVIE France study focuses on women followed for breast cancer in the hospitals where the research is taking place. Recruitment began on 25 March 2024 in one hospital and will progressively start in the other hospitals. Recruitment will run for 12 months. Since the study is based on a comparative approach in order to better understand the respective impact of migration and breast cancer diagnosis, the women included are:

The complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is available in box 1. We chose to include women diagnosed between 2014 and more than 3 years (at the date of data collection) to have at least a 3-year period in which we can document the consequences of breast cancer.

Box 1

The inclusion criteria are as follows:

The exclusion criteria are as follows:

Sample size

The SENOVIE France study aims to include 1000 women, comprising 500 women born in France and 500 women born in sub-Saharan Africa. The women are recruited during consultations in the project’s four partner hospitals. A pragmatic approach has been adopted to determine the size of the study sample, considering the number of patients followed in these hospitals. Around 1785 women born in sub-Saharan Africa and 4375 women born in France were diagnosed with breast cancer between 2014 and more than 3 years (in 2024) and are followed in these hospitals. Based on the 60% participation rate observed in a similar study,54 the recruitment will last 12 months and be stopped at 500 for each group.

The inclusion of 500 participants per group, 500 women born in sub-Saharan Africa and 500 women born in France, would allow us to make comparisons between these two groups, putting in evidence with a statistical power of 80% and a 5% error margin differences between the two groups of women of 9 percentage points or more (see online supplemental appendix 1). For instance, according to official records, 12% of women are diagnosed in late stages for their breast cancer in France.55 In African countries, more than half of women are diagnosed in late stages.56 In our study, we could show a difference between 12% among women born in France and 21% or more among women born in sub-Saharan Africa. Another outcome of interest is the employment trajectory: considering that 7% of women employed at the time of breast cancer diagnosis are unemployed 5 years after,27 if among women born in sub-Saharan Africa this proportion is 16% or more, we will be able to establish a difference.

Based on the eligibility criteria specified above, healthcare professionals will identify eligible patients before or during the consultation. For each health professional, the register lists all eligible patients present at the consultation. It consists of two sections: an anonymous section and a nominative section, which is detached before the registers are handed over to the research team. The register indicates for each eligible patient whether she accepts or refuses to participate, as well as some sociodemographic data such as age, country of birth and activity. The analysis of the registers will enable us to measure participation rates and characteristics associated with non-participation.

For each patient eligible for the study, the healthcare professional will invite the patient to read the study information note carefully. The healthcare professional will then propose the study to the patient. Once the patient agrees to participate in the study, the healthcare professional will complete two copies of the consent form and have them signed by the patient. The healthcare professional will keep one copy and give the second copy to the patient. For each patient agreeing to take part in the survey, the healthcare professional will stick a label with an identification number on an anonymity card and give it to the patient. The patient will give this anonymity card to the interviewer with whom she will complete the questionnaire. The identification number on this card will be used as the sole identifier for the various survey questionnaires (patient questionnaire, biographical grid and medical questionnaire). Women who agree to take part in the study can, if available, meet the interviewer to complete the questionnaire immediately, or make an appointment with the interviewer to complete the questionnaire later, in the days following recruitment and at the hospital where the patient is recruited. Neither the interviewer nor the research team will know the patient’s identity. Informed consent is requested from each patient before the questionnaires are administered. All women participating in the study will receive a €10 voucher as compensation for their participation.

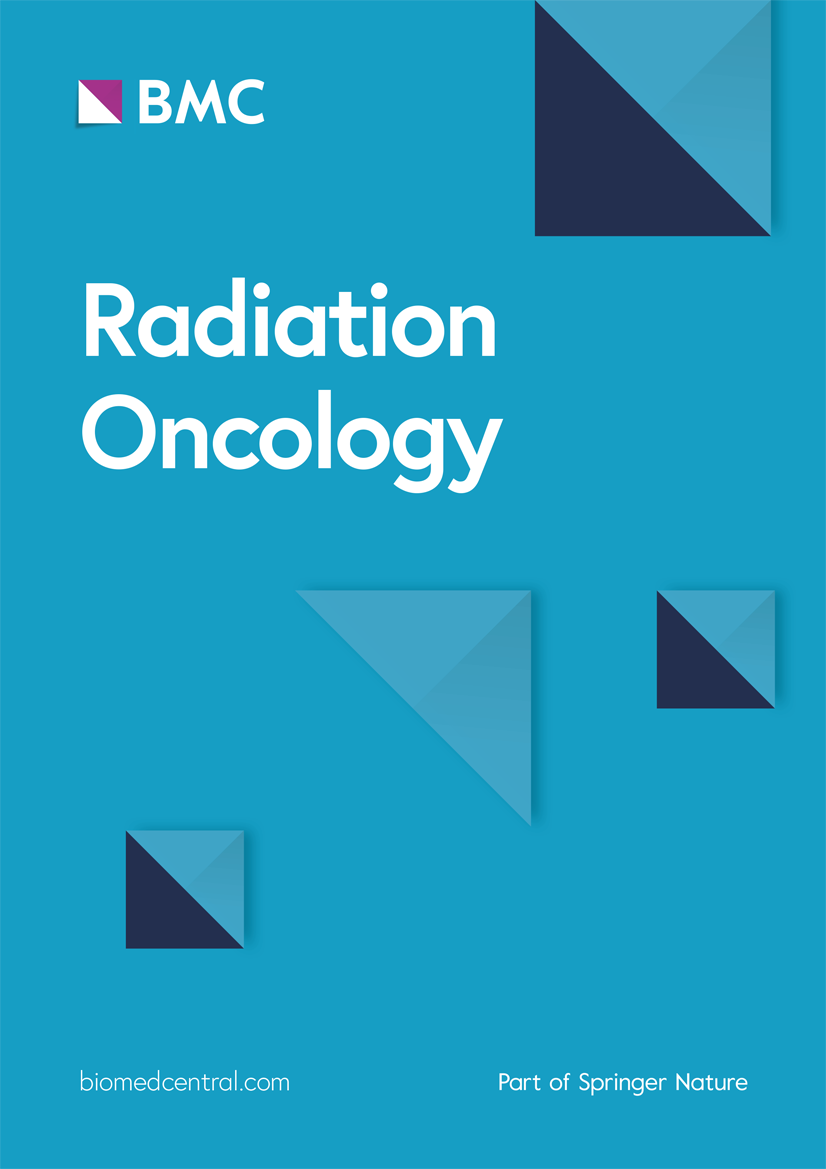

Quantitative data collection is carried out using a patient questionnaire combining a Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) individual questionnaire (online supplemental appendix 2) and a life event biographical grid (online supplemental appendix 3), as well as a CAPI medical questionnaire (figure 2 and online supplemental appendix 4). The life event biographical grid is a paper where the main events that occurred in the patients’ lives are recorded, year by year, from their birth to the time of the survey. A unique patient identification number will be used to merge data from these questionnaires. The CAPI individual questionnaire and the biographical grid will be administered through face-to-face interviews with a trained interviewer on the premises of the project’s hospital partners, in offices that guarantee the confidentiality of the interview. The biographical grid has been shown to help minimise memory bias, as respondents can use both dates and age to remember the order of events, and can put events in relation to each other (eg, a woman may not know when she first gained access to health coverage, but will remember that she obtained it during her second pregnancy).57 The CAPI individual questionnaire and the paper biographical grid will be used to collect detailed information year by year on different dimensions of the life course (online supplemental appendices 2–4):

Figure 2

SENOVIE France quantitative data collection tools. These tools will be used to collect data from each patient included in the study. Data collection using the individual questionnaire and the medical questionnaire (in black) will be done using Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI). Data collection with the life event biographical grid (in red) will be done on paper.

The medical questionnaire contains questions on the characteristics of the cancer and the treatments received by the women. It will be filled in by hospital staff at partner centres on a secured server. More information is provided in the data management plan.58

Collecting data about breast cancer using a life course approach can bring up painful life stories for both the interviewees and the interviewers. To deal with this, the interviewees can call on the psychologists in the health services where they are recruited. The interviewers have weekly exchanges with the research team to share the experiences they have encountered, and they can also call on the psychologists of the institution to which they are attached.

In terms of statistical analysis, descriptive statistics will be used to precisely describe the medical status, social characteristics and living conditions of women born in France and women born in Sub-Saharan Africa living with breast cancer in the greater Paris area. These statistics may also be age standardised if, as expected, women from sub-Saharan Africa are younger than their native-French counterparts. Descriptive trajectory visualisation tools such as sequence analysis could be used for these analyses.59

To measure the social consequences of breast cancer diagnosis and treatments, specific statistical methods for longitudinal data (Cox models,60 discrete-time logistic regressions61 that allow taking different temporalities into account (time since migration, since diagnosis, since treatment, etc) will be used. Specific attention will be paid to how healthcare trajectories may have been impacted between 2020 and 2021 by the COVID-19 sanitary crisis as observed elsewhere,62 and also to examine whether all women were affected in the same way (missing medical follow-ups, delayed surgeries). Special attention will also be paid to the social determinants and social impacts of breast reconstruction. All analyses will be adjusted for the characteristics of the women surveyed to control possible variations. For women born in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the analyses will be adjusted for length of stay in France and administrative status.

Study objective and recruitment procedures

This qualitative study aims to provide an in-depth description of women’s health, social and migration trajectories, and how these different dimensions interact in care pathways. This section aims to answer the following questions: which women circulate and under what conditions? What challenges and obstacles do they encounter? What administrative, material and social difficulties do they face? What levers can be used to overcome these obstacles, and which players can they rely on? What are these women’s professional, family, marital, emotional and physical experiences?

To answer these questions, we will conduct qualitative semistructured interviews with women from sub-Saharan Africa who have come to the greater Paris area for treatment (after having been diagnosed in their country of origin), and with immigrant women diagnosed in France. We aim to conduct around 40 interviews, but the exact number may vary according to the principle of data saturation.63 The women will be recruited from partner hospitals. Immigrant women from sub-Saharan Africa who participate in the quantitative survey will be offered the opportunity to participate in the qualitative interviews. Those who accept will then be referred to qualitative interviewers trained to conduct semistructured interviews using an interview grid (online supplemental appendix 6). We will follow the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research checklist when disseminating results from qualitative data (online supplemental appendix 6).

Data management and analyses

Interviews will be recorded, pseudonymised and transcribed. The qualitative interviewers will make a textual transcription of the audio files, with pseudonymisation of names and places. Pseudonymised transcripts of the interviews will also be deposited on a secure server and made accessible to research team members for analysis. Informed consent is requested before any interviews are conducted, and specific consent is required for audio recordings. The interviews will be analysed using a comprehensive approach64 aimed at analysing the experiences as lived by these women.

The SENOVIE France study is a health study involving human persons. The study is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Committee for Persons’ Protection East (Comité de Protection des Personnes Est-1, national number 2023-A01311-44) in November 2023, and a declaration of compliance with MR 003 has been made to the French Data Protection Authority (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés, declaration number 2231238). The SENOVIE France study is registered on Clinicaltrial.gov (NCT06503393; registration date: 7 September 2024). We will disseminate the findings through scientific publications, policy briefs, conferences and workshops.

The study is currently being carried out by research teams. Patients were not involved in the design of this research. However, contacts are being established with associations of women with breast cancer so that they can participate in the project's dissemination plans in the future.

The SENOVIE study is a comparative study of the health and social trajectories of women treated for breast cancer in some hospitals in the greater Paris area. The original mixed methodology used, which combines qualitative interviews and a quantitative retrospective life-event survey, has demonstrated its robust tracking of life and health trajectories.57 65 It will enable a detailed analysis, year by year, of the differences and similarities of access to healthcare between women born in France and women born in sub-Saharan Africa. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first comparative studies about the social and health trajectories of immigrant women and French-born women treated for breast cancer in France. It will also provide better documentation of the issues involved in access to breast cancer care for immigrant women from sub-Saharan Africa. By focusing on breast cancer, this study broadens the scope of health problems studied among immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa in France to include non-infectious chronic diseases.

The main issue in this study concerns the recruitment of immigrant women from sub-Saharan Africa. Women who travel to France for treatment after being diagnosed in their country of origin are few in the healthcare system in general and therefore, few in the hospitals where the survey is being carried out. According to the number of residence permits issued for treatment in France: out of 287 179 first-time residence permits issued in 2021, 4403 (1.5%) were issued to sick foreigners, all pathologies combined and all nationalities combined.66 Furthermore, the survey population, whether immigrant or not, is subject to survivorship bias,67 that is, the women surveyed are those who survived the disease. Although this selection is consistent with the objectives of the study, it should be noted that the women surveyed could have a different profile from that of women who died of the disease, and therefore not be representative of all women who have been followed for breast cancer. This fact is even more relevant for women born in sub-Saharan Africa, because if they have a life expectancy of 5 years similar to what has been observed in sub-Saharan Africa,1 30 68 there may be few of them in the active wards of hospitals, particularly if they were diagnosed more than 5 years ago. It is also possible that the characteristics of these women are different, insofar as studies show a higher mortality rate among women from disadvantaged social backgrounds.19 As the women recruited had been diagnosed for more than 3 years prior to the study, it is possible that their care pathways differ from those of newly diagnosed women, given recent medical advances. Future studies could explore the situation of these women. It is also possible that the status of the disease, that is, whether it was cured at the time of the survey, influences the women’s responses. However, as one of the strengths of our method is that it documents women’s entire social and health trajectory, that is, before, during and after cancer, we will be able to observe how situations change depending on whether they are still living with cancer or have been completely cured. In the analyses, we will control the different results according to the stage at which the women are.

Despite these different issues, this research will provide scientific knowledge on the circumstances of cancer diagnosis in women born in France and those born in sub-Saharan Africa, on the experience of the disease and its consequences on different aspects of women’s lives (economic, entourage, sexuality, couples, etc). This research will raise the awareness of public health authorities and patients’ associations and perhaps help them to develop specific lines of action for immigrant women and to lobby political decision-makers to promote their access to care. These results could thus contribute to the improvement of medical and psychosocial care for women living with breast cancer. With its life course approach, the SENOVIE Study will provide innovative results on the trajectories of immigrant and non-immigrant women living with breast cancer in France. These results can be key to tackling social health inequalities in breast cancer.

Not applicable.

We sincerely thank all the participants, the interviewer’s team, the health professional team and the members of the SENOVIE study group.