You may also like...

7 Countries Where Valentine’s Day Isn’t February 14

Valentine’s Day isn’t always February 14. Some countries mark love on entirely different dates, and the traditions behin...

Countries That Have Restricted Valentine’s Day Celebration

Valentine’s Day is global but not universally accepted. In some countries, February 14 has been restricted, discouraged,...

What Exactly Is an African Man’s Business with Valentine?

Every February 14, love becomes loud, red and expensive. But what exactly is an African man’s business with Valentine’s ...

9 Ways to Survive Valentine’s Day As A Singlet

Single on Valentine’s Day? Forget the roses and rom-coms; here’s your perfect survival guide to survive the day and cele...

Roses Are Red, Naira Is Not for Bouquets This Valentine

Money bouquets may look romantic, but the CBN has a warning. Here’s why using naira notes as Valentine decorations could...

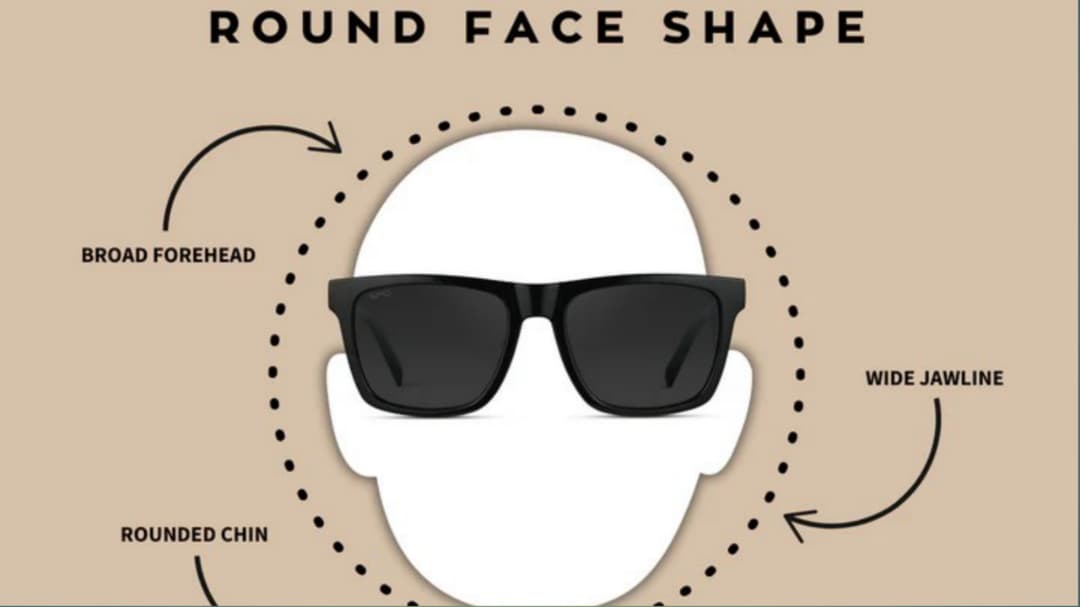

Have a Round Face? Avoid These 5 Sunglass Shapes

Have a round face? Avoid these 5 sunglass shapes that can make your face look wider and know the most flattering frame s...

Heavyweight Showdown! Wardley to Defend Title Against Dubois

The highly anticipated heavyweight title clash between Fabio Wardley and Daniel Dubois has been officially confirmed for...

WAFCON 2026 Host Revealed! CAF President Drops Major News

CAF President Patrice Motsepe has confirmed Morocco will host the 2026 Women's Africa Cup of Nations, dispelling recent ...